June 2022

Welcome to the June edition of the Cloudera Fast Forward Labs newsletter. This month we take a trip down memory lane: re-releasing another gem from the research vault and revisiting two of our recent applied ML prototypes. Then we snap back to the present with some recommended reading.

We’re hiring!

Research Engineer (US/UK/Canada - Remote)

As a Research Engineer on the Cloudera Fast Forwards Labs team, much of your time will be spent developing new applied research and sharing it with the community via reports and blog posts. You’ll also have the opportunity to hone your engineering skills by contributing to and supporting our catalog of applied machine learning prototypes. And as an ML advocate within Cloudera, you’ll be able to influence the shape of our product features to ensure their amenability for ML and data science practitioners.

New (old) Research!

We’ve opened the vault again and released a classic FFL report on semantic recommendations. This report was originally written in 2017 so while some of the specific models discussed may today be replaced by higher-performing counterparts, the overall methodology remains a leading practice in the space.

Semantic Recommendations

Algorithms that understand content — and the preferences of a user in relation to that content — can make better recommendations. Thanks to recent algorithmic advances in the field of embeddings, namely multi-modal models, we have begun to uncover how the semantic content of items relates to a user’s preference. Using these recommendation algorithms is like getting a book recommendation from a friend who knows you well and has actually read the book!

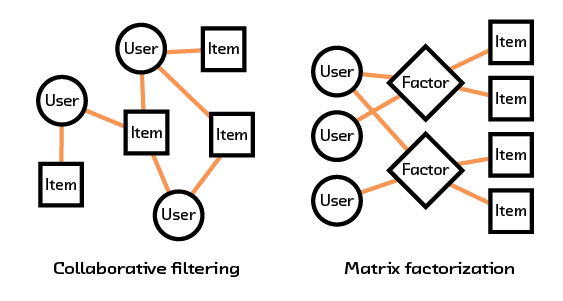

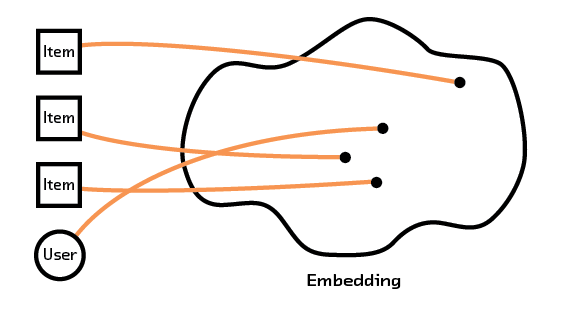

In this report we discuss the field of semantic recommendations, from the history of how it has evolved to the work being done to make the algorithms more widely applicable. We cover classic approaches like collaborative filtering and matrix factorization, and compare these to embedding-based recommendation systems.

These embedding-based systems learn fundamental characteristics about the items or users and create a model that understands how these characteristics (which can come from intrinsic data, such as an image or description of an item) relate to each other. By having our recommendation system extract semantic meaning from that raw data we can form recommendations for items and users we’ve never seen before, avoiding the so-called “cold start problem” that plagues other methods.

New (old) Applied ML Prototypes!

Cloudera’s Applied ML Prototype Catalog Continues to Grow

Recently, our marketing and data science buddy, Jake Bengston, released a blog post on the Cloudera blog that highlights two of our most recent AMPs — Video Classification and Continuous Model Monitoring. While we’ve written about these prototypes before, this blog includes videos by the FFL team that demo how these AMPs work!

Fast Forward Live!

Check out replays of livestreams covering some of our research from last year.

Deep Learning for Automatic Offline Signature Verification

Session-based Recommender Systems

Representation Learning for Software Engineers

Recommended Reading

CFFLers share their favorite reads of the month.

The Good Research Code Handbook

When writing code as part of a research or exploratory endeavor, I often find myself conflicted with the labor of writing “good” code vs. the “quick and dirty” version that takes a fifth of the time — rationalizing my choice by not letting perfection get in the way of progress. While this may save time in the short run, I often find myself hitting major slowdowns later in the project when I inevitably must revisit, refactor, or reuse what I thought was just some quick and dirty hacking. Part of the in-the-moment disincentive is not knowing what it means to write clean, organized code and where to find simple examples.

Thankfully, Patrick Mineault put together an excellent handbook that covers software engineering practices and tools for writing modular, robust code with proper documentation for researchers. I’ve found that the time required to learn these habits upfront pays dividends in time down the road if used consistently. This handbook is my go to reference for each new project I tackle. — Andrew

Sentient language models? We don’t even know what that means.

Earlier this month a Google engineer made splashy news headlines when he proclaimed that LaMDA, a dialog model, had attained sentience. Since then, seemingly everyone has weighed in on the topic with the consensus that, no, LaMDA is not. So what is LaMDA?

Where did LaMDA come from?

LaMDA stands for Language Models for Dialog Applications (read the official paper here or the easier-to-digest blogpost here). LaMDA is a family of models that range from 2 to 137 billion parameters. The largest LaMDA is still smaller than GPT-3 (which clocks in at 175B parameters) but no one raised the sentience alarm for that model. So what makes LaMDA different?

While GPT-3 is a generalized language model that achieved remarkable performance in many natural language processing tasks, LaMDA was specifically engineered for the extremely complex task of open-ended dialog. GPT-3 cannot hold a conversation with you because it was not trained to do so. LaMDA, on the other hand, is the progeny of Meena, a chatbot developed by Google two years ago. LaMDA’s impressive conversational capabilities are largely the result of a common theme in Transformer training: scaling laws. What does that mean?

Meena is a 2.6B parameter model trained on 341GB of text and it represented the state-of-the-art for conversational agents in 2020. LaMDA vastly surpasses Meena, possessing far more model parameters (50x more) that were trained on far more data (4.5x more). This training was made possible by also scaling up the amount of compute, which allowed LaMDA’s training to be completed in a reasonable timeframe. (It still took nearly 2 months to train the largest LaMDA model using more than 1000 TPUs!)

Safeguards

The LaMDA authors note that “while model scaling alone can improve quality, it shows less improvements on safety and factual grounding.” In other words, throwing more data at a bigger model creates a dialog agent more capable of producing fluid and “natural” conversations, but doesn’t necessarily prevent the model from delving into dangerous territory. This is because language models learn statistical relationships from their training data and then feed it back to us. LaMDA’s training data comes from the internet, which is rife with unsavory, unpleasant, and unfair language. Therefore, LaMDA was built with a safety filter to prevent it from making harmful suggestions, propagating unfair biases, offering questionable medical or financial advice, or talking about violence and gore.

Another typical challenge with language models (of any kind) is their tendency to generate language that may seem plausible but is factually inconsistent or incorrect. This stems from the model’s ability to generalize, rather than memorize, the training data. To curb this behavior, LaMDA’s authors fine-tune the model with a toolkit containing an information retrieval system, a translator, and a calculator. Before LaMDA responds with the next segment of dialog, it can literally look up the facts it needs in order to provide a correct response. Handy!

Getting philosophical

The bottom line is that LaMDA was specifically engineered to produce a conversational agent capable of seeming human, with the ability to carry on open-ended discussions on a massive range of topics, using a database of knowledge to look up facts, and with a literal filter to remove nasty comments (I wish some humans had more of a filter!). But does the ability to mimic human conversation make something sentient? Now we’re crossing over into an area where my expertise falters so I’ll turn to the experts.

Brian Christian, a prolific author at the intersection of philosophy and computer science, has this to say in his Atlantic article, “How a Google Employee Fell for the Eliza Effect”:

I believe that AI systems can, in principle, be “conscious”/“sentient”/“self-aware”/moral agents/moral patients—if only because I have not seen any compelling arguments that they cannot. Those arguments would require an understanding of the nature of our own consciousness that we simply don’t have.

And Carissa Veliz, an associate professor of philosophy at the Institute for Ethics in AI at the University of Oxford, put it this way in her recent Slate article, “Why LaMDA Is Nothing Like a Person”:

However, it is a category mistake to attribute sentience to anything that can use language. Sentience and language are not always correlated. Just as there are beings who cannot talk but can feel (consider animals, babies, and people with locked-in syndrome who are paralyzed but cognitively intact), that something can talk doesn’t mean that it can feel.

My take? I’ve read the transcript between LaMDA and the Google engineer; where he sees a person, I see a (very good) language model. And while LaMDA’s creators took many pains to build safeguards into that model, there was one danger they didn’t prepare for: the more human-sounding the chatbot, the more devious the implications for human interaction.

This isn’t the first time we as a society have had this conversation (consider that the Turing test was first posited in 1950), nor will it be the last. It behooves us to continue to advance the fields of neuroscience, biology, and philosophy in lockstep with computer science and machine learning so that we can better answer these questions as they become more relevant. And always keep in mind that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. - Melanie