Sep 5, 2019 · featured post

Transfer Learning - from the ground up

Machine learning enables us to build systems that can predict the world around us: like what movies we’d like to watch, how much traffic we’ll experience on our morning commute, or what words we’ll type next in our emails.

There are many types of models and tasks. Face detection models transform raw image pixels into high level signals (like the presence and position of eyes, noses, and ears) and then use those signals to locate all faces in an image. Time series models can use sensor measurements to extract long-term trends and seasonal patterns in order to predict future observations. Text prediction models extract information about the meaning of past sentences, grammaticality, and emotions in the text in order to predict the next word or phrase that you’ll type.

To do this, we use algorithms to train a model to accomplish a task. At the beginning, the model knows nothing, then we show it examples of training data for that task. As the model sees more and more examples it learns the basic concepts, then finer details, of how to carry out the task. Importantly, models are never explicitly told what types of information to extract; they learn to extract whatever types of information are useful to solving a specific task. Once trained, the model can transform raw data (text, images, gps coordinates, etc.) into useful signals that can then be used to make predictions.

Transfer Learning

Traditionally, a model is trained from scratch, and on only one training dataset, for one specific task. This process is naive and brittle, and it requires lots of data. Transfer learning provides a smarter alternative.

Consider two image classification tasks: in one case a model should learn to distinguish between pictures of cats and dogs, and in a second case a model should learn to distinguish between pictures of cats and bears. Without transfer learning, we would train two totally separate models, each learning the concept of cats and dogs or cats and bears from scratch. But it seems obvious that the type of information that would be useful in distinguishing between cats and dogs (identifying different types of ears, eyes, fur, or common surrounding scenery) would also be helpful in distinguishing cats from bears. With transfer learning, we can use models that already know how to extract useful information because they have learned from other, related tasks.

Imagine that a customer service manager would like to build an automated system to answer simple questions from customers so the customers don’t need to be forwarded to human representatives. Current machine learning technology is sufficiently advanced to build such a system, but would require tens of thousands of question/answer examples, a fleet of expensive processors called GPUs, and an expert practitioner in both deep learning and natural language processing. Not knowing about transfer learning, the manager decides these resources are just too difficult to come by, so the project never gets off the ground.

Now imagine that the manager does know about transfer learning. With transfer learning, the data requirement may be reduced to a few hundred examples, a single GPU will suffice, and a non-expert data scientist can build the system. Transfer learning enables the data scientist to reuse a model that is already trained to extract information from text. This pre-trained model has been trained using easily available, generic, self-labeling data to learn the basics of language. This general understanding of language helps the model with the specific task of question answering. The data scientist can download this model freely from the internet, and then train it on a small amount of data so that it can specialize on the type of data the company has. With transfer learning, the project becomes tenable and a minimum viable product is deployed in a matter of weeks.

Let’s explore how natural language processing models work.

Modern NLP Systems

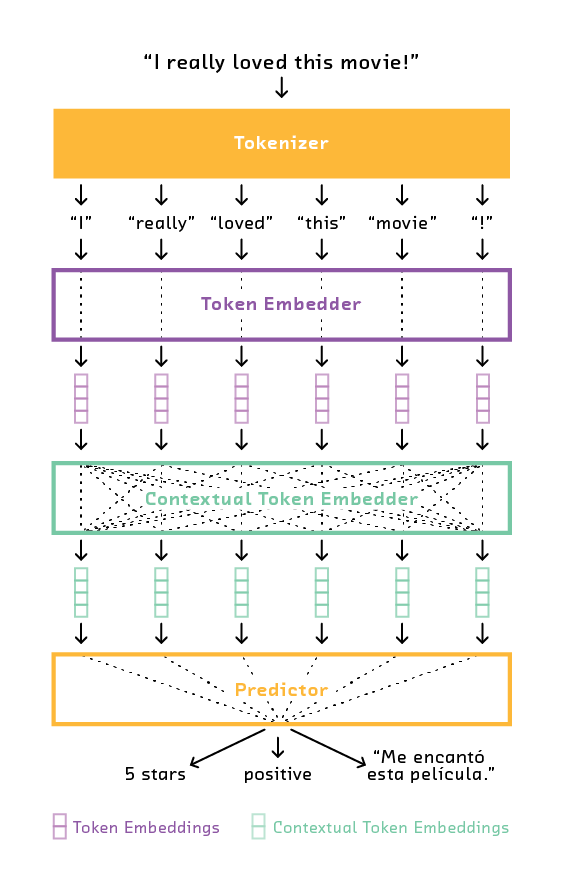

One extremely common input to machine learning systems is natural (human) language, often in the form of text. Machine learning systems can do numerous tasks by processing natural language, including: next-word prediction, identifying sentiment or emotion, extracting topics, or answering questions. Even though these tasks have very different outputs, they all involve extracting similar types of information from text input. In fact, we can break down most any modern NLP system into the following components:

Tokenizer. The tokenizer is a fixed component (no machine learning) that breaks up a piece of text into a sequence of symbols, known as tokens. These tokens might be individual words or letters depending on the type of tokenization used.

Token Embedder. The token embedder turns the individual tokens into numerical form. There are various ways to do this, but most commonly a token embedder learns individual vector representations for each different token. These vector representations are often called word embeddings.

Contextual Token Embedder. The contextual token embedder is responsible for extracting information by analyzing all tokens in tandem. It may learn how tokens interact (e.g., how past adjectives modify a noun), it may take token order into account, and it may build hierarchical features of language. In deep NLP systems, the model is often a type of recurrent neural network. Its output is essentially contextualized token embeddings - continuous representations of tokens that take past or future context into account.

Predictor. The predictor is responsible for taking the contextualized token embeddings and turning them into a prediction of the correct type. When predicting ratings from restaurant reviews, that would be a numerical star rating. For a machine translation system, that would be a string of text in another language.

This common structure for NLP systems is something we can take advantage of. Regardless of the end goal, each system needs a token embedder and a contextual token embedder to efficiently extract useful information from text. In short, a token embedder or contextual token embedder that was trained on one task (prediction) is probably usable and useful in a separate task. Only the prediction component is particularly specific to the prediction task. This means that we don’t need to train these complex components (the token embedder and contextual token embedder) from scratch every time - they can be reused. This helps circumvent challenges relating to lack of data.

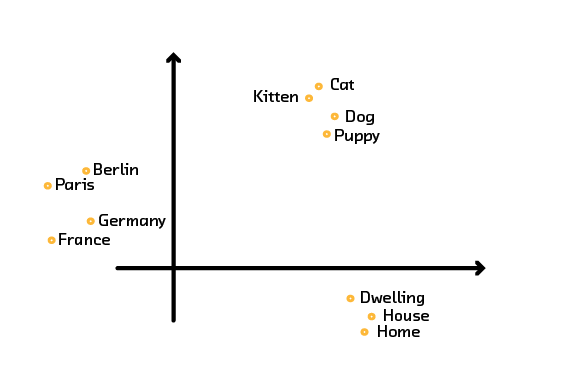

One common example of this is the transfer of token embeddings through algorithms like Word2Vec. Word2Vec uses abundant, publicly available data (like Wikipedia) to learn continuous embeddings for words. The output of Word2Vec is a set of word vectors that preserve some of the meaning of words.

For example, synonyms like “dwelling,” “house,” and “home” may be clustered together. Even analogies like “Paris is to France as Berlin is to Germany” may be preserved. It is clear that token embeddings store some information about the meaning of words that is useful. The meanings of these tokens are the same for most datasets; “dwelling,” “house,” and “home” are synonyms (or at least very closely related) regardless of the dataset. Therefore, it is wasteful to re-learn these embeddings for every new task. With small datasets, it may be impossible to learn them anyway. Instead, we can learn them once from a large, generic dataset, and then reuse them for any model that requires token embeddings.

Transferring the token embedder provides better token embeddings, but the impact is somewhat limited. The contextual token embedder has a far more difficult task - while the token embedder learns the meaning of words, the contextual token embedder learns the meaning of language. Recent breakthroughs in academic research have shown that it is not only possible but extremely advantageous to transfer the contextual token embedder.

Transferring the Contextual Token Embedder

The contextual token embedder is the workhorse of modern NLP systems. It is usually a sophisticated deep learning model (like an RNN or a Transformer) that can do powerful things given enough data. However, in many valuable business applications there simply isn’t enough data to train these models. The consequence is that simpler models must be used instead, which can yield low-performance.

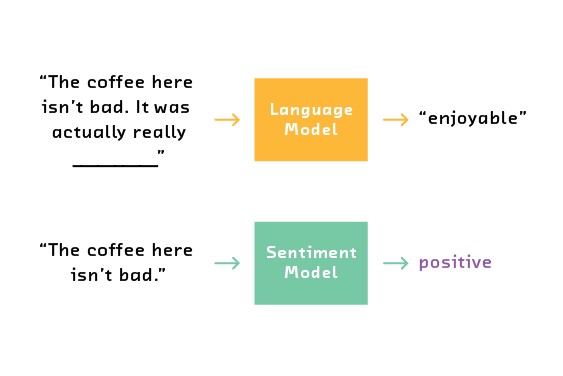

With recent breakthroughs, we can train the contextual token embedder using a related task called language modeling and transfer the “knowledge” of that training to another task. Consider a case where we want to train a model that can extract the sentiment of restaurant reviews. The classic approach would be to hand label a selection of reviews as positive or negative, and then train a model to learn from these examples. But we may not have or be able to get enough data to train a powerful model from scratch. Instead, we can use the task of language modeling which doesn’t require any labels. Language modeling is the task of predicting missing words in a sequence of text.

The key is that language models must learn to extract pieces of information that are relevant to other tasks as well. In this example, a language model needs to understand how negation in the first sentence impacts the missing word - that it is probably positive since “isn’t bad” is similar to ”good.” Similarly, negation is a very important concept in sentiment analysis. So, in the process of training a good language model, we end up training a contextual token embedder that could be useful in sentiment analysis. Crucially, we have far more data points for a language model because it doesn’t require hand-labeling; that is, the labels come from the text itself. The label is simply the next word in the text.

This is one example of a very general strategy for training models: train a language model using an extremely large corpus of text, and then transfer the contextual token embedder from that model to do a related task that is valuable to your business.

There are a number of pretrained models available for download. Google has released a powerful model called BERT, Fast.ai has made ULMFiT available as a part of its libraries, OpenAI has released GPT-2, And AllenNLP has released ELMo. Each of these models has been extensively trained and made available at no cost for use in your applications.

Our Prototype: Textflix

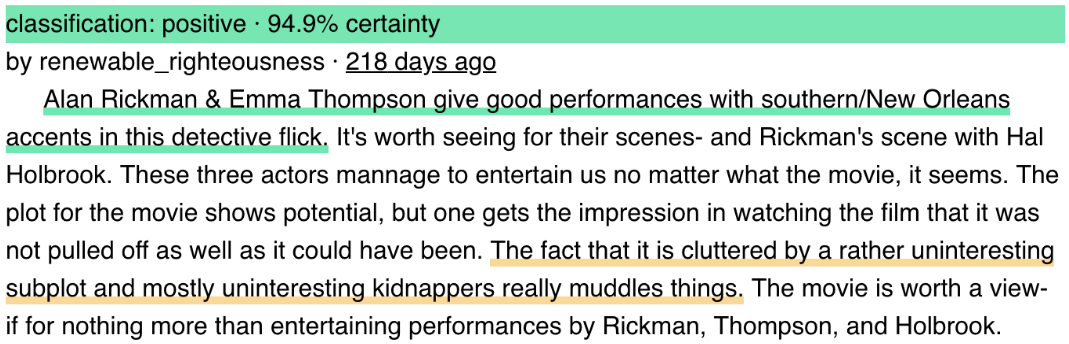

To test and demonstrate this training strategy, we built Textflix, a prototype of a social network for movie watchers. Texflix incorporates automatic sentiment analysis to help users understand which movies are popular and why.

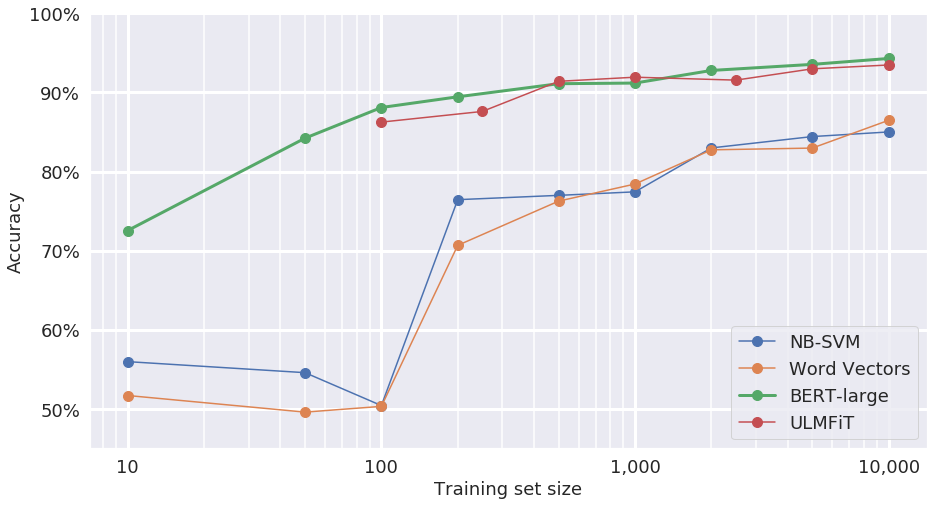

While the dataset we used to build the model behind Textflix had up to 50,000 labeled training examples available, we tested the system with varying-sized subsamples of the dataset down to as few as ten examples. We did this because we wanted to understand how different models, including transfer learning models, would perform with limited data. After all, in real-world problems there is often little or no labeled data available.

To explore how dataset size affects performance, we tested models fine tuned with subsamples of the examples in the dataset to get performance curves for a variety of models.

We compared state-of-the-art models BERT and ULMFiT with baseline models based on naive Bayes support vector machine (NB-SVM) and simple word vector summation. When trained on plenty of data (i.e., 10,000 examples) the transfer learning models greatly outperform the baseline models, reducing the error rate by a factor of 3 (from 15% to 5%). This is due to the fact that the transfer learning models have significantly higher capacity - they are large deep learning models. Because they were pretrained on massive datasets, they do not overfit the relatively small amount of data here; these models were already skilled language processors to begin with. We expect them to outperform the baseline models.

But the more exciting part of the chart is what happens around 100 samples. At 100 examples the baseline models are useless - hardly better than random guessing. The transfer learning models, however, still provide about 88% accuracy which is better than the baseline models can do even at 10,000 samples.

This isn’t just a better model, it’s a new capability: a human can generate enough samples in a short time to get reasonable performance in an NLP system. 100 data samples is manageable for a human to label in a single workday (albeit a tedious one). This lifts the constraint of having labeled data; if no labels are available, simply have a human spend a day generating labels and use transfer learning for the rest.

We built our prototype Textflix using a BERT model trained on just 500 labeled examples. This more closely mimics real-world scenarios where data is extremely limited. The model behind Textflix still provides near state-of-the-art performance despite this constraint.

Transfer Learning in NLP Is Advancing Quickly

Transfer learning in natural language processing is one of the hottest topics in research today, and we’re still exploring its limits. New, more powerful models trained on ever-larger datasets are published frequently, and the state-of-the-art is being pushed higher each time. The improvements to models by simply training them on more and more data is expected to reach a ceiling at some point, but it’s not clear yet where that ceiling is. While this research is technically interesting, end users need not get bogged down by the details. Because these models all obey the common abstractions discussed above, you can benefit by simply downloading the latest models and plugging them in to existing systems today.