Aug 24, 2016 · interview

Next Economics: Interview with Jimi Crawford

Building shadows as proxies for construction rates in Shanghai. Photos courtesy of Orbital Insight/Digital Globe.

It’s no small feat to commercialize new technologies that arise from scientific and academic research. The useful is a small subset of the possible, and the features technology users (let alone corporate buyers) care about rarely align with the problems researchers want to solve. But it’s immensely exciting when it works. When the phase transition is complete. When the general public starts to appreciate how a bunch of mathematics can impact their business, their lives, and their understanding of how the world works. It’s why the Fast Forward Labs team wakes up every day. It’s why we love what we do. It drives us. And it’s why we’re always on the lookout for people who are doing it well.

Orbital Insight is an excellent example of a company that is successfully commercializing deep learning technologies. 2015 saw a series of improvements in the performance of object recognition and computer vision systems. The technology is being applied across domains, to improve medical diagnosis, gain brand insights, or update our social media experience.

Building on his experience at The Climate Corporation, Orbital Insight CEO & Founder Jimi Crawford decided to aim big and apply the latest in computer vision to satellite imagery. His team focused their first commercial offering on the financial services industry, honing their tools to count cars in parking lots to infer company performance and, transitively, stock market behavior. But hedge funds are just the beginning. Crawford’s long-term ambition (as that of FeatureX) is to reform macroeconomics, to replace government reports with quantified observations about the physical world. Investors have taken notice.

We interviewed Jimi, discussing what he learned in the past, what he does in the present, and what he envisions for the future. Read on for highlights.

You’ve been in artificial intelligence long enough to see the rise and fall of different theoretical trends. How has the field evolved over the years?

AI was different when I did my doctorate at UT Austin in the late 80s. Machine learning as induction from data wasn’t as important as it is now. We were concerned with getting computers to know what people know when they think or make true statements, which meant using variance of first-order logic as foundation of knowledge. The goal of our research was to program human common sense into a system using logical - or symbolic - techniques. While this branch of AI has since been eclipsed by machine learning and statistical techniques, there are still challenges in intelligent systems (like mimicking common sense) that will likely only be solved by synthesizing symbolic and neural (deep learning) techniques. We can make a loose analogy to the structure of the brain: a small part is the cerebral cortex, which executes logical thought; the rest is a dense, complex network of neurons.

Does that mean that near-term advances in AI will continue to involve human-machine partnerships as opposed to straight-up automation?

I think that will be the case for the foreseeable future. Even in chess, a very controlled, rules-based game, joint human-computer teams beat teams of only computers or only humans. If we add the complexity of real-world data and real-world problems, things only get messier. At Orbital Insight, we consider computers to be a mechanism to focus human attention on the objects and entities in the world that have significance for a given task or purpose (e.g., counting how many cars there are in a store parking lot at a given time of day). The world is big. Without computer vision tools, we’d need 8 million people to review and analyze satellite images at one meter resolution to get the insights we derive using automation. That’s a massive economy of scale.

You’ve had a rich career, having worked at NASA, Google Books, and the Climate Corporation before founding Orbital Insight. Are there parallels between the problems you worked on at Google Books and those you work on at Orbital Insight?

Google Books was deeply inspirational for Orbital Insight. In essence, both projects are about taking a complex input and transforming it into a simple output people care about. At Google Books, the input was images of millions of book pages. The project’s main purpose was to improve Google’s search engines. We’d digitize images, pass them through an OCR pipeline to figure out what the text was, and annotate them with copyright information etc. The goal was to transform all this raw information into the quotes and passages people could search for and cared about. At Orbital Insight, we follow a similar human-computer data processing pipeline, preparing images, analyzing them with convolutional neural nets, and processing them to output the information people care about, like how many cars are in a company parking lot.

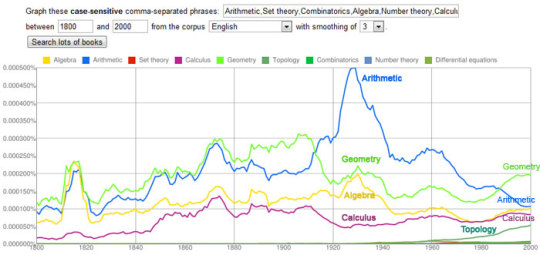

There were some interesting takeaways from the Google Books project. One of our 20% projects (i.e., the 20% of work time Google employees are free to devote to creative research projects) was the Ngram Viewer, which displays graphs showing how different words or phrases occur in book corpuses over selected years. Using the tool, we were able to see a shift from saying “the United States are,” at the signing of the Constitution, to “the United States is,” right around the Civil War. Some linguists used the Ngram Viewer to correlate verb conjugation regularity with frequency of use: the tool shows that conjugations of verbs like “to be,” which are used all the time, vary more frequently.

N-gram of mathematics trends from 1800-2000.

Orbital Insight is a data product company, where development involves the right balance between data science and software engineering. How do you manage that balance?

When I was SVP of Science and Engineering at The Climate Corporation, I had about 100 people on my team. A little less than half were data scientists; the rest were software engineers. That experience taught me to think carefully about the gap between prototypes and products. Many data scientists are not trained as computer scientists: they are comfortable writing prototypes in R or Python, but then pass models to computer scientists to rewrite code for production. Leadership teams have to be mindful of what it takes to go from prototype to bulletproof production code, and include that in timelines and collaboration between teams.

What kinds of problems are Orbital Insight data scientists working on?

We have an interesting mix at Orbital Insight. Part of the team specializes in computer vision, using convolutional neural nets to interpret satellite data. They transform pixels to numbers. We are in the business of counting objects in images, which differs from the classification techniques used for object recognition (as the Fast Forward Labs team researched with Pictograph) that dominate the literature. Say the task is counting how many cars are in a parking lot. We classify each pixel, cluster together areas in the image that contain cars, and then count number of pixels. We hit challenges if we change contexts. The algorithms are trained to count cars in retail parking lots, so don’t automatically transfer to, say, the lot of a car manufacturing plant, where makers place cars inches apart to squeeze in as many as possible. This space differential muddles the clusters. So we have to retrain algorithms for different contexts.

The second group of data scientists is focused on analytics and statistics. They transform numbers to English. They take the millions of numbers about parked cars and distil this information into a single sentence that matters for the user. These scientists have different backgrounds and PhDs than the computer vision team, so I do think a lot about helping them collaborate successfully.

What are some other challenges you face working with satellite data?

We’re limited by what we’re able to collect. The satellites we work with orbit over the geographical space where retailers conduct business on a daily basis. That means, we may see the parking lot of a Walmart store in Massachusetts every day at around 10 am, and a different branch in the midwest every day at 2 pm. So we have to compute a time of day curve for every retailer, and do some statistics to get the timing right. We can back up any inferences with six years of data. The other limitation is that we don’t have data about parking lot patterns in the evening. So our technique really doesn’t work for certain sectors, like evening restaurant chains or movie theaters.

You get to see and work with multiple satellite providers. What hardware developments are you most excited about?

The most interesting developments for us are the ability to use new spectral bands and the increased frequency of imagery. Counting cars falls within the bandwidth of human vision, but there are other applications we’re keen to work on that require low-range infrared or ultraviolet. We want to do things like predict the right spot to mine for iron ore, predict crop health based upon soil moisture levels, discern if a building is occupied or unoccupied based on heat levels, or discern whether a power plant is active. A few new vendors are using novel detectors to push outside of human visual spectrum.

The uptick in image frequency, provided by companies like Planet (with whom we just partnered), provides more data to drive more accurate insights. This shift is remarkable, and is enabled by new hardware and rapidly falling costs. What’s interesting here is when Moore’s Law applies and when it doesn’t. The laws of optics don’t follow Moore’s Law, but the ability to mass produce devices does. Development has therefore not been focused on getting higher and higher resolution from space: in most use cases (like counting cars), getting satellites to 1 or 0.5 meter resolution is perfectly fine, as people want to measure and count things we can also see. So the more useful development was to mass produce hardware, to make cheaper commodities that could be reused and relaunched….and may eventually lead to Elon Musk launching a million vehicles into space.

What is Orbital Insight’s long-term vision?

We want to understand the Earth. It’s amazing how poor our current understanding is: people review government reports and stock reports that say, for example, that steel up and crops are down, but it’s all really just guesses upon guesses given the absence of ground truth. And if you probe economists, their analyses are inevitably built on government reports. Our vision is to replace these reports - and this system - with quantified observations. We want to be able to measure and track the physical world economy like we currently measure and track the digital world (clicks, views, likes).This will impact stocks, agencies, and supply chains: major aircraft manufacturers, who worry about titanium supply, will be able to track how titanium mines are functioning. In short, we want to help rebuild economics on top of real-world observations.

Headshot courtesy of Orbital Insight

What recent developments in machine learning are you most excited about?

Deep learning has only just gotten started. It has tremendous power. AlphaGo beating the world Go champion is mind bending: Go is an intuitive, visual game that is far more complex than chess. And we’re just getting started, especially when we apply this algorithmic power to data from the internet of things. We’re testing this model at Orbital Insight. We’re a data company, but a highly differentiated data company that fuses techniques to create reports that are valuable and hard to create. There are a tremendous number of new data streams, and the game is on for entrepreneurs and data scientists to explore the data, push the algorithms, and create something that is truly unique and new.

What advice would you give to young entrepreneurs looking to push the boundaries and build something new?

We just had a party to celebrate a successful B round and what struck me was the number of folks present who helped get the company started. One great thing about being in Silicon Valley is the access to people and resources who truly support you if they see your vision and think you can be something someday. At the beginning, people gave us free office space, made dozens of intros, shared countless pieces of advice. I’d tell young entrepreneurs to build and rely on their network, and to be open to their input and sensitive to their feedback. Everyone in my network said Orbital Insight was a great idea. And it helped to act with the confidence of a clear signal from the beginning.