Jan 22, 2016 · interview

Eli Pariser on the Ethics of Algorithmic Filtering

Chiefly his reflection, of which the portrait / Is the reflection, of which the portrait / Is the reflection once removed. / The glass chose to reflect only what he saw / Which was enough for his purpose: his image / Glazed, embalmed, projected at a 180-degree angle.

— Parmagiano and John Ashbery - Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror

Personalizing experiences and recommendations for consumers is the goal of many data science efforts, so much so that the NYC Media Lab created Personalizationpalooza to unite technicians and media leadership around the topic. And while studies have shown that recommendation algorithms promote happy consumers, it’s questionable that also they promote healthy citizens.

Zeynep Tufecki, for example, recently wrote a Medium post explaining how Facebook’s focus on “engagement” as a metric for deciding which content to share on user news feeds can happen “to the detriment of the substantive experiences and interactions” she (and others) wants on Facebook. Zufecki illustrates her point with an instance where users felt morally unable to “like” a video with child refugees surrounded by dead bodies. She argues that the platform needs different mechanisms and metrics to ensure that content worth viewing can compete with the content we’re more apt to “like.”

Tufecki is not alone in her concerns. In 2011, Eli Pariser, CEO of Upworthy, wrote the first monograph about the risks algorithmic filtering poses to citizenship and society. The Filter Bubble is still worth reading today, as it provides a framework for understanding how filtering algorithms work and what personal, social, and political consequences they may have. It’s critical we understand these tools now that the 2016 election season is in full swing.

We recently interviewed Pariser to see how his thinking has evolved in light of recent algorithmic progress. Keep reading for highlights.

Upworthy has received a lot of attention for using clickbait to engage readers. While you recently pivoted your content strategy (and redesigned your logo), what problem was the site originally trying to solve?

A hallmark of a critic is the ability to point out a problem but not propose a good solution. After publishing The Filter Bubble, I was invited all over to give talks about how personalized media techniques generate hollow models of individuals, generating the risk that people only see banal content as opposed to the more important things they aspire to read to play their part as citizens. I didn’t want to be one of those annoying people who can only point out a problem. I wanted to actually work on a solution. So, I got together with Peter Koechley, at the time an editor at the Onion, and we decided to collaborate on a project to repurpose the algorithms used to curate and spread highly shareable content on topics people should read to make good decisions and be good citizens. Upworthy was the result.

What’s the new strategy?

We have our own proprietary content management system and collect enormous amounts of data each month on user behavior to track and understand how people engage with content. With storage so cheap and computing so fast, it’s easy for us to collect an enormous amount of data. The hard part is making that data actionable, especially for our creative staff, who are storytellers rather than quants. So our focus is on harvesting behavioral data as insights our writers can use to tell better stories. Think of making writing for the web like standup comedy: you put out a riff, see whether people laugh, and refine it to make more people laugh in the future.

What distinguishes Upworthy from comparable sites?

Our focus on promoting engagement and sharing enables us to write a fraction of stories comparable sites promote. We reach about 100 million people per month with only about 200 stories. Other sites of a similar size and user base generate thousands of pieces of content per month to reach the same audience.

What is the concern about personalization algorithms you addressed in The Filter Bubble?

There is way more information on the internet than any of us could ever read and way more products than we could ever buy. As such, personalization algorithms play an important role, but the problem is that you can end up in an uncanny valley of the self, where the model guiding personalization represents not the full you with all your interests, but only a bad 2-D version of you. Take Netflix as an example. Say you sign up and watch two romantic comedies. You may also love Italian neorealism, but the Netflix recommender system will base its representation of what you like on the data it has. This limited representation then gets amplified through future recommendations. I called this a “you loop” in the book.

What are the implications beyond repetitive recommendations?

For one, we can generate a false impression that we have the ability to make informed choices. The core issue with personalization algorithms is that they shape not only what you see, but also what you don’t see. When we do something as minor as watch a movie or buy a product, or as major as vote for president, we must be aware of the fact that, by simply trusting algorithms, we can’t measure the degree to which we base choices on the full set of available options.

Facebook published an article in Science in May 2015 that drew a large critical response from the community, including critiques from Zeynep Tufecki and Christian Sandvig. The Facebook article argued that, “compared to algorithmic ranking, individuals’ choices about what to consume had a stronger effect limiting exposure” to content with opinions against a user’s stated ideological affiliations. Where do you stand on that?

I agree with Tufecki that personal choice compounds rather than exculpates algorithmic filtering. Sure, beliefs influence what people are interested in, and, in turn, what they click on; but you have to be a very determined reader to dig beyond the limited range of options presented by the tools. The result is that most of us are then exposed to a doubly small range of content. It’s our right as consumers to ask ourselves how much agency we want to make choices about what we see and don’t see.

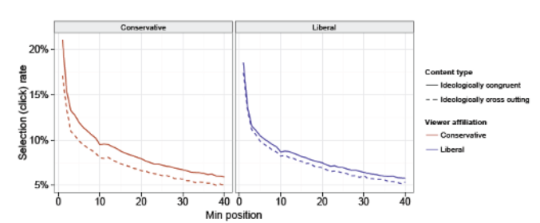

A chart from the appendix of the Facebook report, showing that the higher an item is in the newsfeed, the more likely it is clicked on.

If personalization risks exacerbating political polarization, where can constructive cross-partisan exchange occur online?

One of my favorite discoveries while researching The Filter Bubble was that constructive cross-partisan conversations occurred in two unlikely places: message boards for sports teams and fan space for the television series Lost. The fact that people shared something in common, e.g., they were all Giants fans, created a trusted space for open disagreement about race, class, and other delicate social issues. When united by a common reference point, people are more apt to engage with ideas than in an adversarial, debate-focused context.

What can technologists do to address issues created by algorithmic filtering?

There are two main things: 1) accepting that behavioral signals are insufficient to explain a person, and working to increase our understanding of human psychology, and; 2) building recommendation systems that try to account for people’s aspirational desires as well as their current behavior. That people click more frequently on celebrity stories than political essays does not mean they don’t want to learn about what’s going on in world. One thing that’s interesting about Facebook’s models of the self, versus Google’s model of the self, is that our Facebook identities are somewhat aspirational. Some dismiss our socially-doctored self as inauthentic. I like to celebrate it as aspirational.

What can consumers do to escape algorithmic filter bubbles?

Marshall McLuhan was prescient (side note: we love this classic Annie Hall scene). The first step is for consumers is to become more conscious about the interplay between the medium and message, to accept that our actions on popular websites shape what future stories we’ll see and won’t see. Only then can we learn the basic algorithmic rules and use them to our advantage. In the 70s and 80s, a generation of people figured out how news editors think and why certain stories made first-page headlines to the exclusion of others. Our generation’s task is to understand how people writing algorithms think and what metrics they’re using to promote one story over another. And then, to make the effort to read things of less interest to our present self than to the future self we aspire to become.

(For those interested in art history and early modern optics, Tim’s Vermeer is a fantastic study of the techniques Vermeer may have used to create his works.)

- Kathryn