Sep 1, 2017 · post

Why your relationship is likely to last (or not): using Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME)

Henry VIII of England had many relationships. We build a classifier to predict whether relationships are going to last, or not, and used Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) to understand the predicted success or failure of given relationships.

Last month we launched the latest report and prototype from our machine intelligence R&D team, Interpretability, and we shared our view on why interpretability matters for business.

On September 6, we will host a public webinar on interpretability where we’ll be joined by guests Patrick Hall (Senior Director for Data Science Products at H2o.ai, co-author of Ideas on Interpreting Machine Learning) and Sameer Singh (Assistant Professor of Computer Science at UC Irvine, co-creator of LIME). There will be lots of opportunities for the audience to ask questions, so we hope you’ll join us!

During our research, we built an interpretability prototype called Refractor to better understand the reasons why a subscription business loses customers. This prototype depends on Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), a new algorithm and open source tool for interpreting the behavior of machine learning models that was released last year (paper, code).

We discuss LIME in depth in our report, but in this article, we take look at it from a conceptual perspective and apply LIME to a binary classification problem: predicting whether couples stay together, or not.

Why we need interpretability, especially now

Algorithms decide which emails reach our inboxes, whether we are approved for credit, and whom we get the opportunity to date. But, as algorithms give answers, they raise questions. If an algorithm denies your loan application, wouldn’t you like to know why or what you could change for a more positive outcome? Or perhaps you’d like to know if your bank is right to trust the algorithm in the first place.

Fundamentally, machine learning algorithms learn relationships between inputs and outputs. During model training, we supply examples of these inputs and outputs as “learning material” and the algorithm learns the relationship, a parametrized function or trained model. It uses this model to provide outputs for novel inputs.

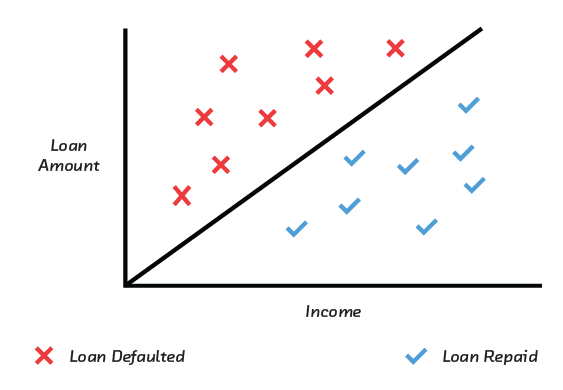

Some relationships are simple and can be captured by simple, linear models, which are easy to inspect and understand. For example, the probability of loan default increases with loan amount and decreases with income. These models are interpretable, meaning, they allow a qualitative understanding between inputs and outputs.

The simple, linear relationship between income, loan amount, and loan default.

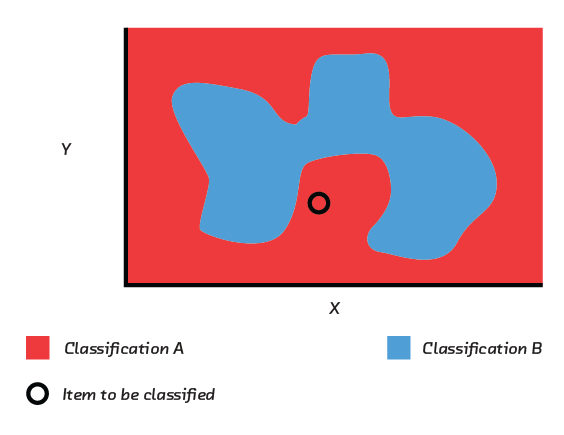

But some relationships are complex. A customer’s decisions to cancel a subscription, the focus of our Refractor prototype, or the long-term success of a romantic relationship may depend on multiple factors in non-linear ways. To accurately model these relationships we need models with the flexibility to capture that complexity. Models such as random forests, gradient boosted trees, and neural networks can do just that. But, these complex models are intrinsically difficult to inspect, understand and interpret.

Complex, non-linear relationships, as shown in this figure, cannot be captured by simple models. Models that can capture this complexity tend to be less interpretable.

The promise of interpretability for practitioners

Interpretability means we can understand the reasons why an algorithm gave a particular response. In a recent blog post we cover why, from a business perspective, one should care about interpretability.

But data scientists and machine learning practitioners benefit from interpretability, too. Interpretability ensures that a model is right for the right reasons and wrong for the right reasons, which traditional measures of model performance, such as model accuracy on the hold-out test set, cannot capture. Insights into the model can help improve it and can help build trust that the model, once deployed, will continue to do a good job.

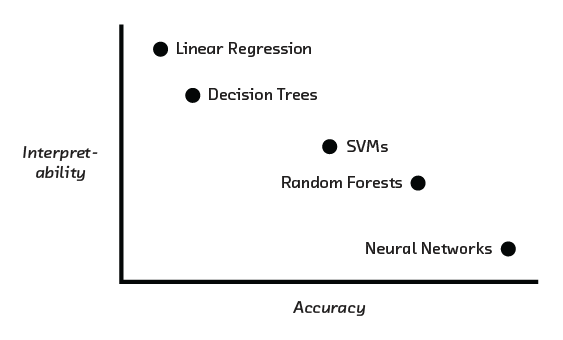

One approach to ensure interpretability is to use simple models, but the trade-off between interpretability and accuracy means that, if relationships between inputs and outputs are complex, accuracy will suffer.

More accurate models tend to be harder to inspect and understand.

Another option is to use “white-box” models. These have been developed specifically to provide insight into their internal workings without sacrificing model accuracy too much. We cover white-box models in our report.

Model-agnostic interpretability and LIME

But what if you don’t want to (or can’t) change your model? Perhaps there’s no other way to get the accuracy you need. Perhaps it’s already in production. Or perhaps you didn’t make it and have no idea how it works. In these situation, “model-agnostic” interpretability tools such as LIME may be the right approach (paper, code). LIME is based on two simple ideas: perturbation and locally linear approximation.

Perturbation

Perturbation is probably exactly what you would do if you were asked to explore a black-box model. By repeatedly perturbing the input and observing its effect on the output you can develop an understanding of how different inputs relate to the original output.

LIME formalizes this idea. It takes a prediction you want to explain and systematically perturbs its inputs. These perturbed inputs become new, labelled training data for a simpler approximate model.

Locally linear approximation

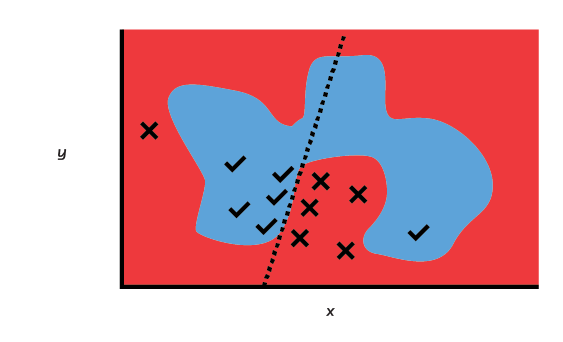

LIME fits a linear model to describe the relationships between the (perturbed) inputs and outputs. In doing so, it weights generated labels close to the example more heavily to nudge the algorithm to focus on the most relevant part of the “decision function”. So, the simple linear algorithm approximates the more complex, non-linear function learned by the high-accuracy model locally, in the vicinity of the to-be-explained prediction.

Even complex decision functions can be approximated locally by simple linear models.

Based on two simple ideas, LIME is an exciting breakthrough. It allows you to train a model in any way you like and still have an answer to the local question, “Why has this particular decision been made?”

Putting LIME to work, explaining the (predicted) fate of romantic relationships

Love endures forever but when it doesn’t, wouldn’t you like to know why? We took the Stanford HCMST data (How Couples Meet and Stay Together), a longitudinal study on how American’s meet their partners, and build a classifier to predict whether (and why) couples are likely to stay together.

We modeled the relationship between couples and their relationship fate using a random forest classifier, a widely used ensemble model that is difficult to inspect and understand. Popular machine learning libraries offer simple ways to implement machine learning routines. We used sklearn's’ RandomForestClassifier for model training, GridSearchCV for hyperparameter tuning, and Pipeline to streamline data preprocessing. If you want to see the code, and experiment with LIME, you can access the notebook here.

To explain predictions, once we had a trained model, we needed to instantiate the LimeTabularExplainer object. It takes as inputs a list of feature names (feature_names) and class names (class_names), a list of all categorical variables (categorical_features) and a dictionary of the values of all categorical variables (categorical_names) in addition to the training data; LIME perturbs inputs according to the training data distribution.

from lime.lime_tabular import LimeTabularExplainer

# The Lime LimeTabularExplainer object

explainer = LimeTabularExplainer(

train, # training data

class_names=['BrokeUp', 'StayedTogether'], # class names

feature_names=list(data.columns), # names of all features (regardless of type)

categorical_features=categorical_features, # names of only categorical features

categorical_names=categorical_names, # labels of all values of all categorical features

discretize_continuous=True

)

The LimeTabularExplainer object has a method explain_instance that takes an example input and returns the top reasons for its corresponding prediction. The explain_instance method requires a function (pipeline.predict_proba) as input that takes the “raw” example input data, transforms, scales, one-hot encodes, etc. (as appropriate), and returns its prediction using the trained model. To see how we made ours, see our notebook.

example = 3

exp = explainer.explain_instance(test[example], pipeline.predict_proba, num_features=5)

print('Couples probability of staying together:', exp.predict_proba[1])

exp.as_pyplot_figure()

sklearn's Pipeline streamlines data preprocessing and helps build the function for the lime explain_instance method (see code). Why the trouble, you may wonder? We could supply scaled, one-hot encoded example input to the explain_instance method?

To explain predictions, we need to be able to understand the reasons returned by solutions like LIME. If LIME returned a sequence of numbers that, mathematically speaking, is a good explanation for a prediction, we would be none the wiser. Explanations needs to be given in a language and at the scale the we can understand; that’s why we need to bother with Pipeline.

Why relationships (are predicted to) fail

According to the model, across couples based on random forest’s feature importances only, your age, your partner’s age, and the difference in age between partners determines whether couples are going to stay together, or not. LIME shows that the reasons for likely relationship success vary from one couple to the next.

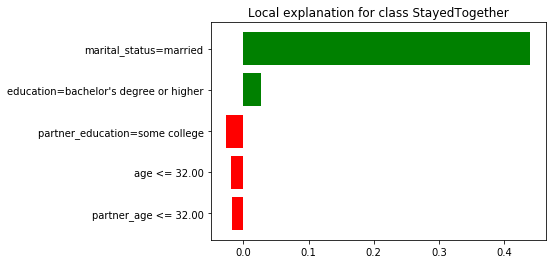

This couple is likely to stay together, the model gives it a 0.89 probability. LIME informs us that the prediction is due to the fact that the couple is married while their (young) age lowers their chances of relationship “success”.

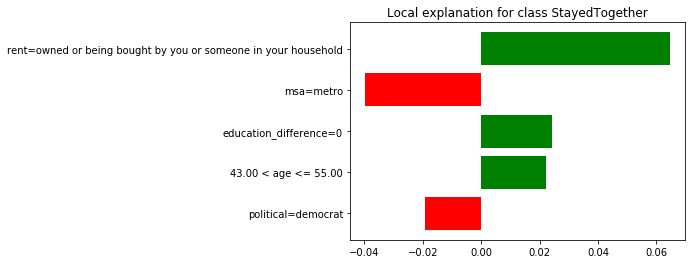

This couple is likely to stay together, the model gives it a 0.75 probability. LIME informs us the prediction is due to the fact that the couple owns their home, they are matched in terms of the level of education, and the respondent is between 43 and 55 years. Curiously, living in an urban area and voting democrat is associated with a lower chance to staying together.

LIME captures nuances above feature importances, the variables the trained model deems important globally, across the entire data encountered during training (age, partner’s age, age difference). LIME focuses on individuals, not global patterns.

What LIME reasons are not (good for)

How about using algorithms to manage your love life strategically? The model suggests to look for a partner close in age. Should you ask for a pay increase, buy a house, or get married? We asked LIME.

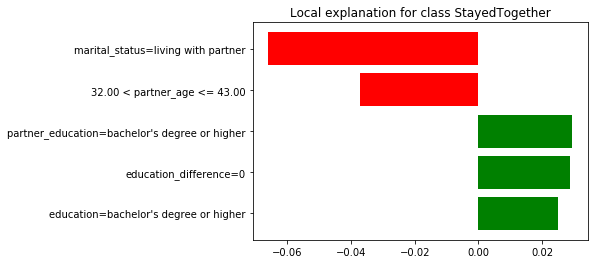

Your chances of staying together aren’t bad, the model gives is a 0.79. But merely “living together” is hurting your chances, according to LIME.

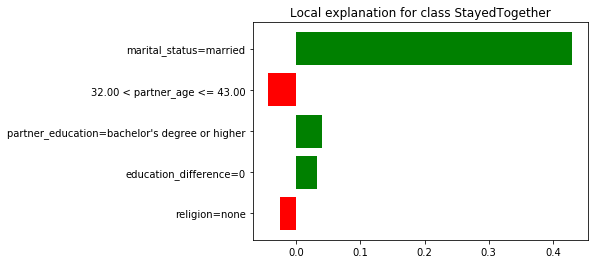

Evaluating different options, getting married leads to the biggest increase in your chance of staying together. But, we advice against marrying tonight’s Tinder date. It may be tempting to treat LIME’s reasons as causes of the real-world phenomena the model is predicting; surely, a high amount of debt on my loan application is the reason (read “cause”) for my denied loan application (especially if a smaller debt amount would have changed the outcome).

Getting married increases your chance of staying together to 0.91. But, reasons are not causes. We advice against marrying tonight’s Tinder date.

Algorithmic relationship advice should be taken with a grain of salt, LIME reasons are not causes. Interpretability helps us understand the inner workings of models to improve these models, to help build trust in models, and to form hypotheses about phenomena in the real-world captured by models (that warrant rigorous tests).

What’s more, LIME picks up on patterns in the data learned by the model, it does not inform about reality. Data reflects current and past conventions and social practices (which we see in our results). LIME is no oracle, but it allows humans to enter a more collaborative relationship with black-box machine learning models, and question them when necessary.

As we’ve said before: “The future is algorithmic. White-box models and techniques for making black-box models interpretable offer a safer, more productive, and ultimately more collaborative relationship between humans and intelligent machines. We are just at the beginning of the conversation about interpretability and will see the impact over the coming years.”