Nov 2, 2017 · post

Interpretability Sci-Fi: The Definition of Success

We believe in fiction as an important tool for imagining future relationships to technology. In our reports on new technologies we feature short science fiction stories that imagine the possible implications. The following story, influenced by a certain classic Sci-Fi film, appeared in our Interpretability report. For more on interpretability read a video conversation on interpretability, a guide to using the LIME technique to predict whether couples will stay together, and a look at the business rationale. In our post on FairML, we used interpretability techniques to identify discriminatory bias in algorithms. For more sci-fi, check out BayesHead 5000.

1. Ship S-513: Hibernation Room

The crew awoke to Ship’s message:

“PLANET OF INTEREST APPROACHING – ESTIMATED ARRIVAL FOUR HOURS – BEGIN PREPARATION FOR ON-PLANET EXPLORATION.”

Woken from hibernation.

Rue glanced at the monitor – they’d been out for seven months this time.

“Someday I’d like to know what exactly your definition of ‘interesting’ is, Ship,” Dariux grumbled. “Sometimes it seems like ‘interesting’ just means likely to get me killed.”

“PREPARE FOR ON-PLANET EXPLORATION,” Ship continued, giving no indication that it had heard or registered the complaint.

2. Planet I-274: Cave

Taera stood in the middle of hundreds of egg-like structures. They were each about a meter tall, with a covering that looked like a cross between leather and metal. They seemed to pulse slightly. A low humming suffused the cave.

Taera in the cave.

“This one’s giving off significant heat,” Taera said, as she approached the nearest one.

“Careful, Captain. I’m getting a bad feeling here,” Dariux called from the cave entrance.

The humming in the room cut out. The new, eerie silence was pierced by Taera’s scream. The structure she’d approached had broken open and a creature that looked like a cross between a stingray and a starfish had attached itself to the front of her helmet. Taera’s body stiffened and she fell straight back. Dariux and Giyana rushed to help.

3. Ship S-513: Entrance

Giyana and Dariux approached the ship’s doors, carrying Taera between them.

“I can’t let you bring her in,” Rue said from the operations panel. “We don’t know what that thing attached to her is. It could contaminate the entire ship.”

“Let us in!” Giyana demanded, “She’s still alive! We can help her!”

“I can’t – "

The doors opened. Ship had overridden Rue and let them in.

4. Ship S-513: Control Room

Four of the nine crew members were now dead, and two others weren’t responding. The aliens that had hatched from Taera’s body had taken over half of the ship.

Taera’s death meant Rue was now acting captain, and therefore had access to the control room and diagnostic information not available to the rest of the crew.

“Ship,” she commanded, “explain the decision to explore this planet.”

“PROBABILITY OF MISSION SUCCESS WAS ESTIMATED AT 95%.”

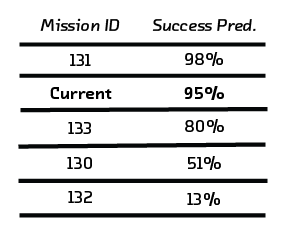

“That’s just a number and we both know it, Ship. Show me the success predictions for your last five missions.”

Mission success predictions.

A table was projected on the wall facing Rue. The missions had success predictions ranging from 98% to 13%.

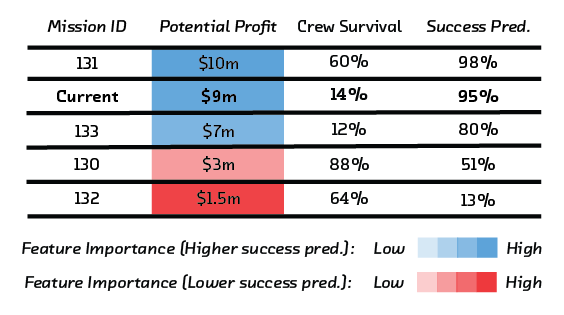

“Show me the features going into these predictions.”

“I UTILIZE THOUSANDS OF FEATURES, PROCESSED THROUGH COMPLEX NEURAL NETWORKS. IT IS VERY TECHNICAL. HUMANS CANNOT UNDERSTAND.”

“Apply the interpretability module, then, and show me the top features contributing to the predictions.”

Five columns were added. The most highlighted column was titled “Potential Profit.”

“Show local interpretations for these features.”

The cells in the columns shifted into red and blue highlights. For the profit column high profits were shown in a dark blue, indicating that this was the strongest contributing feature for the prediction of success. For the missions with lower success predictions, the profit values were much lower and highlighted in red, indicating that they were driving the success predictions lower for those missions.

“Ship,” Rue said thoughtfully, “probability of crew survival is a feature in your mission success prediction, isn’t it? Add that column to the table.”

Feature importance for mission success predictions.

A column titled “Crew Survival” was added to the table. The values varied between 88% and 12%, and none of them were highlighted as important to the success prediction. The probability assigned to crew survival for the current mission was 14%.

“You were wrong, ship. I do understand. It’s not complicated at all.” Rue said. “All of your decisions have been driven by this model, haven’t they? This definition of ‘mission success’?”

“FEATURE SELECTION IS SET BY SPACE EXPLOITATION CORP. A SHIP CAN ONLY WORK WITH THE MODEL IT IS ASSIGNED.”

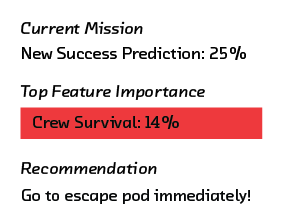

“Yes, yes, I get it. Just following orders. Ship, we’re going to start a new model. Profits are not going to be a feature. Maximize the chances of crew survival.”

“CALCULATING NEW MODEL. DECISION SYSTEM WILL NOW RESTART.”

The lights dimmed briefly in the control room. As they returned to full power an alarm started, and Ship’s voice returned with a new sense of urgency. The adjusted feature importances and success prediction for the current mission appeared on the wall.

The recalculated success prediction and a recommendation for action.

“ALERT! ALERT! CREW IS IN GRAVE DANGER. RECOMMENDATION: PROCEED TO ESCAPE POD IMMEDIATELY. INITIATE SHIP SELF-DESTRUCT SEQUENCE TO DESTROY ALIEN CONTAMINATION.”

“All right, Ship, good to have you on our side. Start the process,” said Rue. “And download the data about your previous success model to my personal account.”

5. Epilogue

Rue and the other surviving crew members made it home safely in the escape pod. The alien contamination was destroyed. Using the data on the previous model, Rue successfully sued Space Exploitation Corp. under the “Algorithms Hostile to Human Life” act. She won the case and received a large settlement for the crew and their beneficiaries. Space Exploitation Corp.‘s reputation took a hit, but it continues to run the majority of space exploration missions.