Jan 26, 2018 · newsletter

Serverless data science

Cloud computing has transformed enterprise IT. It makes it possible to rapidly scale up and down a complex and global infrastructure, without the overhead of a datacenter. But living in the cloud can be expensive, and you still need to maintain computers and their operating systems, even if they are virtual. That’s why we’ve been watching with interest the rise of “serverless” computing.

Serverless has the potential to open up “big data” work to mere mortal data scientists who don’t have the budget or engineering support for a long-lived analytics cluster, and to make life simpler and reduce costs for those that do.

Traditional cloud “elastic compute” systems (like Amazon’s EC2, Google’s Computer Engine, or Azure’s Virtual Machines) allow you to run applications without maintaining hardware. The goal of “serverless” is to go even further, and make it possible to run applications without worrying about hardware or the operating system.

Serverless environments (like Amazon’s Lambda, Google’s Cloud Functions, or Azure’s Functions) can be thought of as computing environments that pop into existence for the duration of a single function call, and are then destroyed. Configuring and maintaining the underlying operating system is somebody else’s problem.

Because the serverless instance exists only for the duration of the function, there’s no idle time and your bill scales almost perfectly with the amount of compute you use. Combined with the fact that you no longer need to configure and maintain the operating system, this can result in big savings. For example, our friends at Postlight converted their Readability application to run on AWS Lambda and reduced the monthly cost from over $10,000 to $370.

But it’s not all good news. Because the environment ends after the function finishes, input and output must occur via a web API or a database connection. There is no internal state or disk. And the various cloud providers place CPU, RAM, time, and programming language constraints on what you can do. (For example, AWS Lambda functions must run Python, C#, node.js or Java; R is not an option. And the function must return in less than 300 seconds and use no more than 1.5Gb of RAM.)

These limitations might seem to make serverless less appealing to power-hungry data scientists and data engineers - and indeed, so far most of the prominent uses of serverless have been in web applications, where the computational requirements are less intense. But in many ways the constraints of serverless are similar to those faced in distributed analytics clusters running Hadoop or Spark. To do data analytics in these environments, we have the map-reduce computing paradigm, which parallelizes work by splitting it into small parcels.

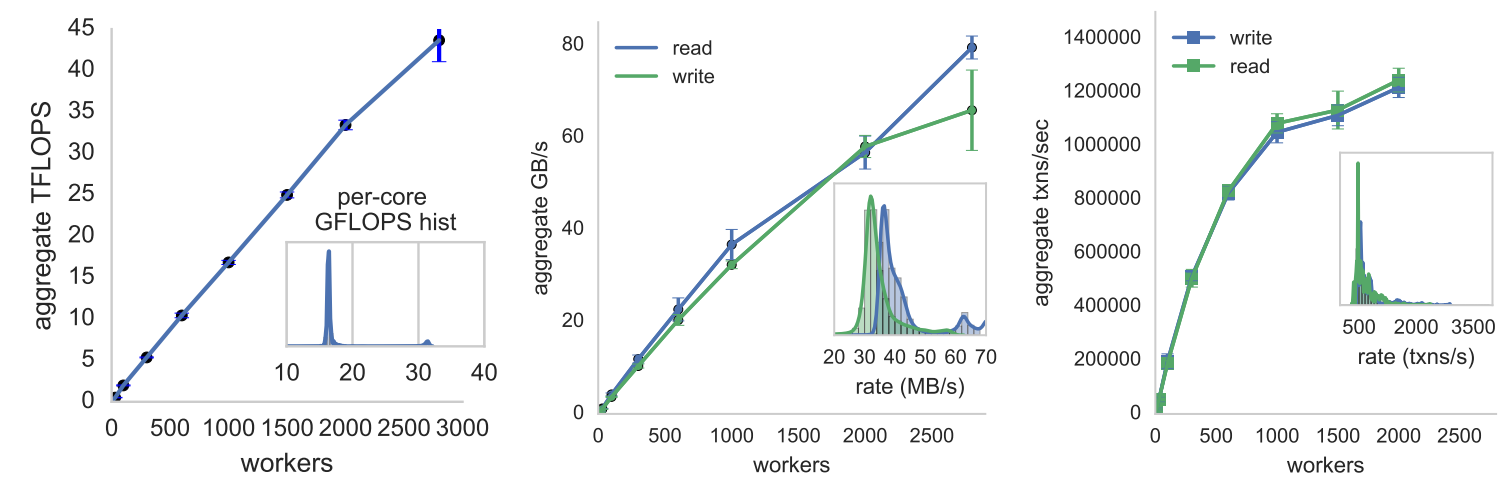

PyWren’s computational power can grow to many TFLOPS as the number of workers (inexpensive AWS Lambda instances in this case) increases. Image credit: Occupy the Cloud: Distributed Computing for the 99%

PyWren is a distributed analytics tool that connects the dots. It splits up large analytics jobs into smaller parcels of work, and ships them off to hundreds or even thousands of serverless AWS Lambda instances. This makes PyWren (with AWS Lambda as a computational “backend”) a light-weight alternative to complex, expensive (and admittedly more robust) map-reduce frameworks such as Hadoop and Spark.

And - perhaps most intriguing for us at Cloudera Fast Forward Labs, given our interest in machine learning - it’s exciting to see serverless used to speed up hyperparamter optimization, a relatively simple (but computationally intensive) part of model building.

For more on PyWren, see Occupy the Cloud: Distributed Computing for the 99%. For more on the implications of serverless more generally, see Serverless Computing: Economic and Architectural Impact.