Feb 28, 2018 · newsletter

Comparing human and agent performance: DeepMind releases PsychLab

Google’s DeepMind released PsychLab this week, which has been developed internally and released to the public as part of DeepMind’s efforts to apply decades of research in cognitive science/neuroscience to advance the state of the art in machine learning and artificial intelligence. Many modern machine learning models have taken inspiration from principles derived from decades of research in cognitive science/neuroscience. This announcement, along with the accompanying paper, provide an open-source playground for testing how agents (built using LSTM deep learning alrogirthms) perform when compared to humans on a slew of cognitive tasks that are fairly well-understood and widely used to study human perception.

The research findings point out some potentially non-obvious ways in which the models used to build artificial agents are missing some fundamental aspects of how primate (human and non-human) vision and cognition operate. For instance, one experiment that tested psychophysical thresholds of an agent found that visual acuity was affected by the size of the images presented. This led researchers to build a secondary model that loosely approximated the fovea (the center of the retina at the back of the eye, where sight is most acute) to improve performance. The need for this secondary model was only made clear by comparing performance of the agent to human performance and relating the difference back to human physical anatomy.

Interestingly, the agent failed to produce many well-known effects in humans. The pattern of differences between humans and the agent isn’t complete enough yet to make any big theoretical claims, but it appears that the agent has some deficits in integrating information over time, yet is spared the deficit typically seen in humans when asked to search for an object composed of the conjunction of two features (e.g., orientation and color). As these patterns continue to emerge, they will inform how new models are developed and will more clearly delineate the fundamental differences between how agents and humans perform cognitive tasks.

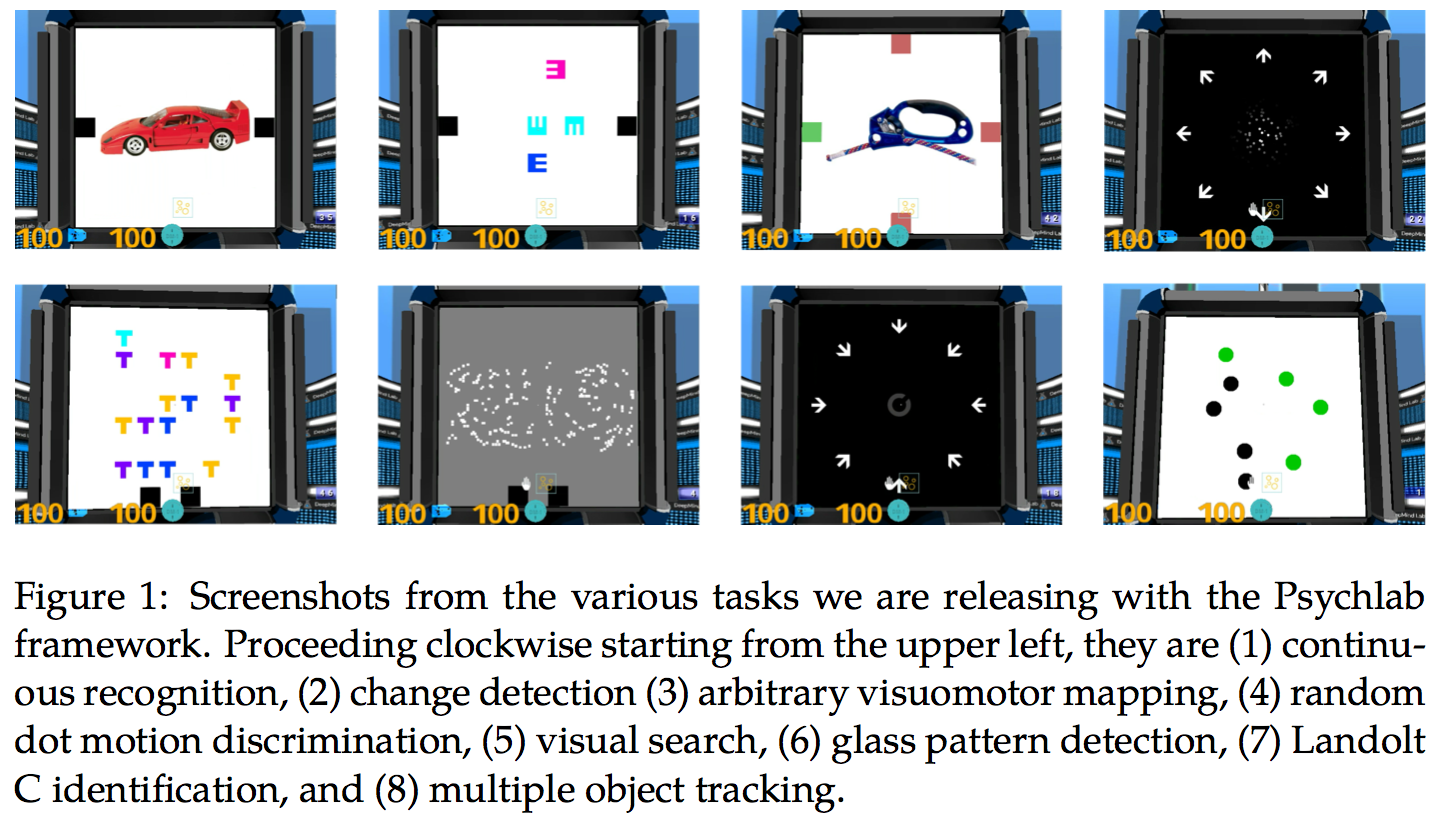

Figure from the PsychLab paper

Most of the machine learning models in production today, as opposed those used for more pure research, are aimed at automating tasks typically performed by humans or augmenting already-existent human capabilities. Currently, many practitioners make tuning decisions to increase the efficiency of machine learning models, but may be inadvertently making trade-offs that affect how well their models actually reliably replicate or augment human abilities. This collaboration between machine learning and cognitive science/neuroscience research, as it evolves, will bring to light new potential approaches to decrease that error.

This type of open-source release allows practitioners to test their models on a myriad of cognitive tasks. This will greatly increase the speed at which machine learning models will change based on cognitive science/neuroscience. This burgeoning era gives us a moment to pause, however, and think critically about what a particular business might want to gain by using machine learning. It’s clear that we’re not yet near a generalized Artificial Intelligence (and these experiments reinforce that idea). As machine learning algorithms borrow more and more from cognitive science/neuroscience, we can think of these models in different ways. We can think of them as evolving along the same trajectory as humans (akin to studying infant brains and how they change and evolve throughout a human’s life); we can look at these models as something related to human cognition, but fundamentally separate (akin to the research on non-human primates); or we can think of these models as performing something entirely their own - with no tie to human evolution or development.

As this field continues to develop, and we begin to employ machine learning in every facet of business, it’s important to establish and maintain a goal for these tools, perhaps with these distinctions in mind.