Feb 28, 2018 · newsletter

Machine Learning In The Browser

The promise of Machine Learning (ML) on edge devices holds potential to enable new capabilities while reaping the benefits associated with on-device computation. As an environment that is frequently the source of data (user interactions, sensors such as cameras, acelerometers, etc.), the browser within PCs, mobile and IoT devices represents an important edge “platform.” Deploying models in such environments can improve latency for interactive applications, reduce model distribution costs, and enable privacy as data is no longer sent to remote servers for analysis.

In recent times, advances in graphic acceleration in the browser (WebGL), increasing compute capabilities on edge devices, and the advent of JavaScript-based ML frameworks make ML in the browser particularly exciting.

Why Machine Learning in the Browser?

Latency

By bringing computation directly to the user, there is opportunity to improve application latency. This is especially true for tasks that may or may not be computationally intensive but have been traditionally performed on remote servers. For example, recommendation tasks such as predicting a user’s next action (that previously involved roundtrip calls to a remote server (upload user data, process, download result)) can be performed in the browser with faster response times.

Privacy

Perhaps, one of the most compelling strategies for building user trust in a product is to offer objective notions of privacy. In many cases, systems designed to be provably private (“we do not store your data”) can be more convincing than systems which offer privacy assurances (“we store your data, but only use it for specific known purposes”). With ML in the browser, it is possible to perform analysis on a client’s data on their device via the browser and provide value to them without transmitting their data to any servers for processing. An example is the ability to offer language translation or image captioning or document classification services for sensitive content in the browser. Within the same framework, models can be trained on a user’s local data and used to provide improved, personalized services.

Distribution

Setting up a traditional environment for running ML models can be tedious and challenging to deploy. While these issues can now be addressed with the use of docker containers as well as dependency management packages, it is still challenging to package and distribute applications with ML models on end user devices. The process of bundling a client application that first installs frameworks such as Tensorflow or Pytorch, simply for the purpose of enabling ML capabilities, can be error prone, and varies with the distribution platform.

On the other hand, browser based deployments can leverage the standardized web environment with zero installation costs for the user and distribution costs for the developer. Costs associated with building for multiple platforms (e.g., CPU architectures, Operating Systems) are also avoided as mature web standards allow web applications to remain stable across these environments.

Libraries for Machine Learning in the Browser: Tensorflow.js

There are several open source libraries which provide a simple JavaScript API that allows users to build and train machine learning models in the browser. These include projects such as Tensorflow.js, ConvnetJS, Brain.js, Synaptic, Neataptic, WebDNN and Mind.

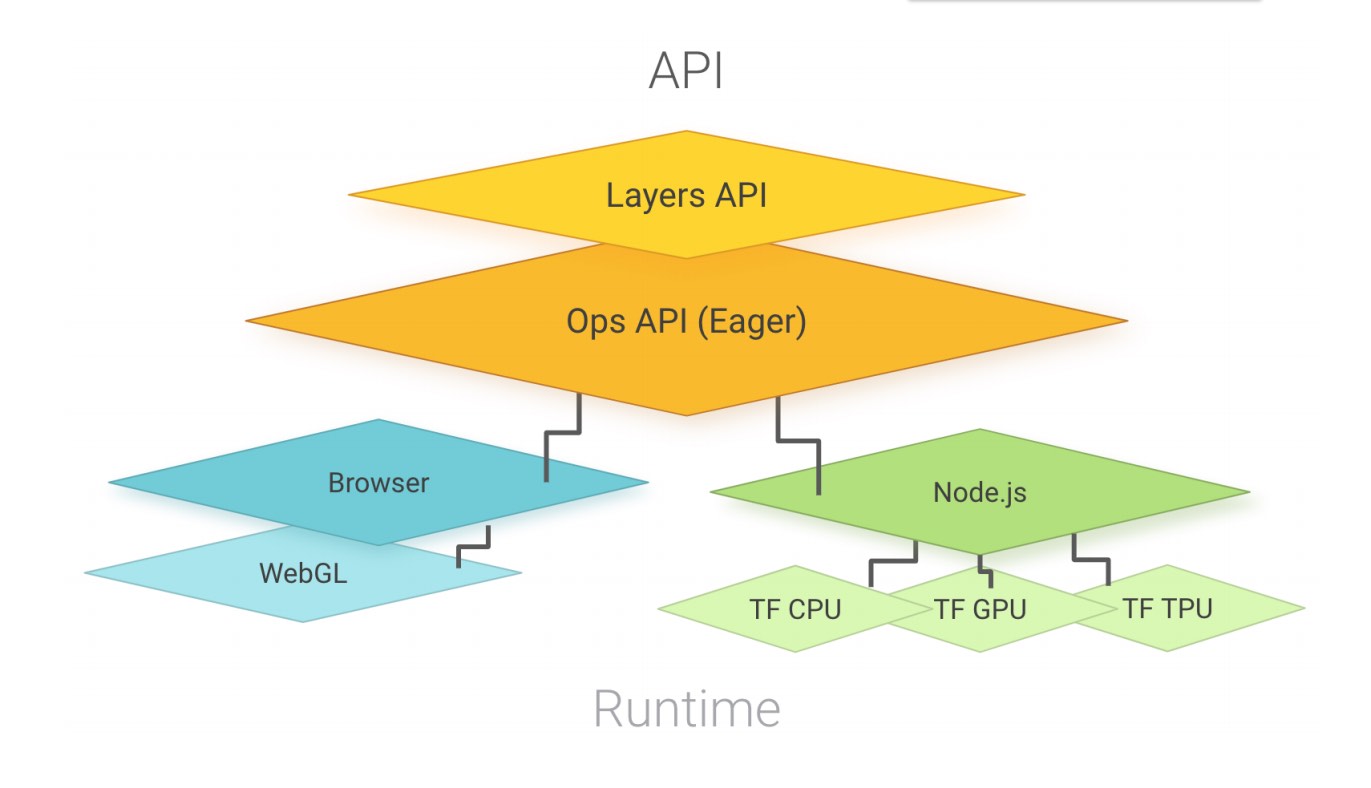

As of right now, Tensorflow.js appears to be the most mature API in terms of maintenance, integration with the broader ML ecosystem, and community adoption. TensorFlow.js consists of two sets of APIs: the Ops API which provides lower-level linear algebra operations (e.g., matrix multiplication, tensor addition, etc.), and the Layers API, which provides higher-level model building blocks and best practices with emphasis on neural networks. The Layers API is modeled after the tf.keras namespace in TensorFlow Python, which is based on the widely adopted Keras API and supports rapid prototyping of complex ML models.

Figure shows the architecture of the Tensorflow.js library. source

TensorFlow.js is designed to run in-browser and server-side, as shown in the figure above. When running inside the browser, it utilizes the GPU of the device via WebGL to enable fast parallelized floating point computation. In Node.js, TensorFlow.js binds to the TensorFlow C library, enabling full access to TensorFlow. TensorFlow.js also provides a slower CPU implementation as a fallback (omitted in the figure for simplicity), implemented in plain JS. This fallback can run in any execution environment and is automatically used when the environment has no access to WebGL or the TensorFlow binary. (See the Tensorflow.js paper here.)

Tensorflow.js integrates well with the broader Tensorflow ecosystem by providing a converter which also allows users to convert, load, and run existing Tensorflow models. Developers can build, train, optimize and test their models in Tensorflow (Python) and then export the resulting model for use in the browser.

Current Applications and Outlook

With Tensorflow.js, users can prototype and run models of varying complexity from simple linear/polynomial regression to complex neural networks for image recognition, object detection, pose detection, and Natural Language Processing.

There have also been interesting applications ranging from prototyping handsfree interactions for increased accessiblity, hand gesture interaction and numerous examples for teaching ML concepts. Furthermore, and as we mention in an earlier report, Tensorflow.js can enable Federated Learning where locally trained models (not data) from participating devices are shared with a central server. The server combines these into an updated federated model which is then shared with each device.

While these usecases are still emergent, one important limitation for ML in the browser is related to the single-threaded nature of JavaScript applications in the browser. Browsers typically have a “main thread” where JavaScript code, event processing, and other instructions are run. It does not support a multi-threaded paradigm (though research in this area is active) and can be less performant than other programming environments. If designed incorrectly, a compute intensive ML operation can “block” the main thread, which can hamper the overall interaction experience for users.

As edge devices become more compute capable, it is likely that more processing, including model training and inference tasks, will be shifted to the browser. It is also likely that more third party libraries and design patterns will begin to integrate the use of ML models in the browser.