Oct 26, 2017 · newsletter

Bias Mitigation Using the Copyright Doctrine of Fair Use

Pirating a copyrighted song, video, or e-book to listen to the song, watch the movie, or read the book is an infringement of copyright (which can be severely fined). So how about pirating a song, video, or e-book to train machine learning models?

NYU Teaching and Research Fellow Amanda Levendowski proposes a legal approach to reducing bias in machine learning models. Biased data leads to biased models, she argues, and use of existing public domain data, most of which is over 70 years old, introduces biases from a time before, e.g., the civil rights movement or the feminist movement of the mid-20th century. The copyright doctrine of fair use can reduce bias by allowing wider access to copyrighted training data - an interesting and novel proposal.

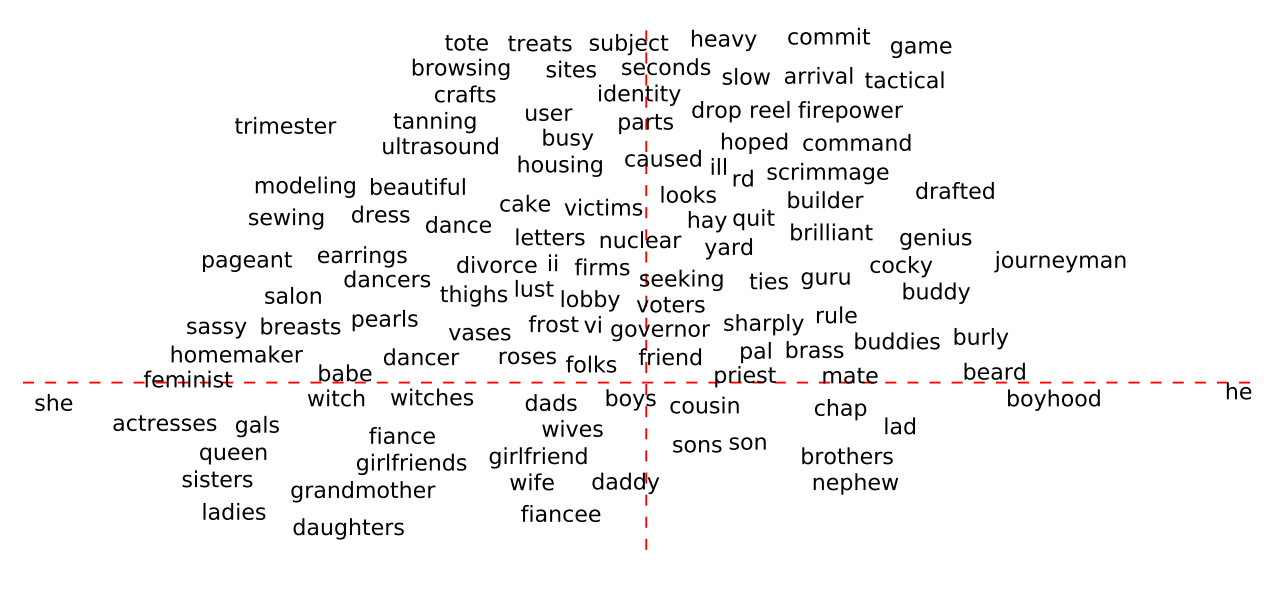

Word embeddings (numerical representations of language) are biased. While words like “he” vs. “she” or “wife” vs. “husband” are gendered words and should fall on opposite ends on the “gender axis” (x). Words like “brilliant” should not (image taken from Bolukbasi et al.).

Fair use is a legal doctrine that operates as a defense to copyright infringement. This century-old exception essentially gives a get-out-of-jail free card to copiers who would otherwise be liable for copyright infringement. Fair use doctrine permits the copying of copyrighted material on the grounds that the type of copying is beneficial to the public and not unreasonably harmful to the copyright holder.

Courts have not yet ruled on fair use in the machine learning context, though it seems likely that they will need to soon. And once courts have ruled on a few such cases, those rulings will set a precedent for subsequent similar situations. If the precedent allows fair use, machine learning researchers will have the freedom to use copyrighted material with little fear of infringement liability.

Levendowski argues: (1) use of copyrighted materials to train machine learning models should be considered fair use and (2) the resulting availability of these copyrighted materials as training data will help mitigate bias in the models trained with that data.

Levendowski steps through each factor in the legal test for fair use and makes good arguments for why machine learning model training should be fair use. The strongest of these points is that the use is transformative, i.e., it is not used for its primary purpose. For example, a copyrighted music recording was made to be sold and listened to by humans, perhaps over the radio or on a smartphone. Using that same recording to train a model would be a very different use, and one that advances our understanding of music. Courts have held that this weighs in favor of fair use. Also notable is the argument that the copyright owners are not harmed by the use. Using the recording in the example above does not prevent the copyright holder from selling or licensing the recording.

A neural net model trained on romance novels generates captions for images; fair use might remove bias, but it surely entertains (we recommend you check out the authors’ alternate model trained on Taylor Swift lyrics).

We find Levendowski’s fair use analysis persuasive from a legal standpoint, but the benefits, though real, are overstated. Applying fair use may reduce bias, but it would be very unlikely to fix it (as suggested by the title How Copyright Law Can Fix AI’s Implicit Bias Problem). There’s no reason to believe, for example, that a set of recent textbooks would contain any less bias than Wikipedia (data used already during model training).

Bias has many origins, some rooted in legal and social practices. To reduce bias in machine learning models, we need to change these practices. We hope that the federal courts, which will inevitably be faced with these copyright infringement lawsuits, will consult and heed Levendowski’s analysis.