Aug 28, 2019 · newsletter

Is machine learning research moving in the right direction

Research in machine learning has seen some of the biggest and brightest minds of our time - and copious amounts of funding - funneled into the pursuit of better, safer, and more generalizable algorithms. As the field grows, there is vigorous debate around the direction that growth should take (for a less biased take, see here). This week, I give some background on the major algorithm types being researched, help frame aspects of the ongoing debate, and ultimately conclude that there is no single direction to build toward - but that through collaboration, we’ll see advances on all fronts.

image taken from https://systemdesign.intel.com/inferring-the-future-of-machine-learning/

One place where debates over whether machine learning is heading in the “right” direction hit a major roadblock is when those debating the issue don’t have a clear and agreed upon destination. There tend to be three general goals:

-

For some who dedicate their lives to researching, developing, and testing machine learning algorithms, the ultimate goal is something akin to artificial general intelligence often referred to as AGI and equally as often mis-labeled with the much narrower term “AI”. The goal of this line of research is to create a machine that can operate in the world in a way that’s indistinguishable from humans (and likely pass the turing test).

-

For others, machine learning is a promising tool to model the human brain and further our understanding of human cognition.

-

Still others are focused solely on building commercially viable products that can replicate and automate simple processes, and (in some cases) even outperform humans on highly specific tasks.

Each goal stated above requires a different weighting of the algorithms being used, and hence a differential investment in lines of research. I won’t belabor the landscape of possible machine learning research areas here, but to ensure everyone reading this has at least a basic understanding of the landscape, I’ll touch on a few key areas.

- Deep learning (a type of neural network with many layers) has seen an explosion in terms of research over the last 7 years, mainly employing supervised learning (check out our recent report on Deep Learning for more).

- Reinforcement learning (also a neural network) is an algorithm that aims to choose the optimal behavioral action in an environment given a pre-specified goal to achieve the largest cumulative reward (a lot of the research in this area is being led by Google’s DeepMind and OpenAI).

- Natural language processing is a larger field in computer science, but recent work has focused on using recurrent neural networks to glean meaning and even generate language (several of our research reports utilize NLP).

A problem with most of these neural network-based techniques is that they are very data hungry. A lot of recent research has been dedicated to finding ways to train these algorithms with less data (see our report on Learning with Limited Labeled Data).

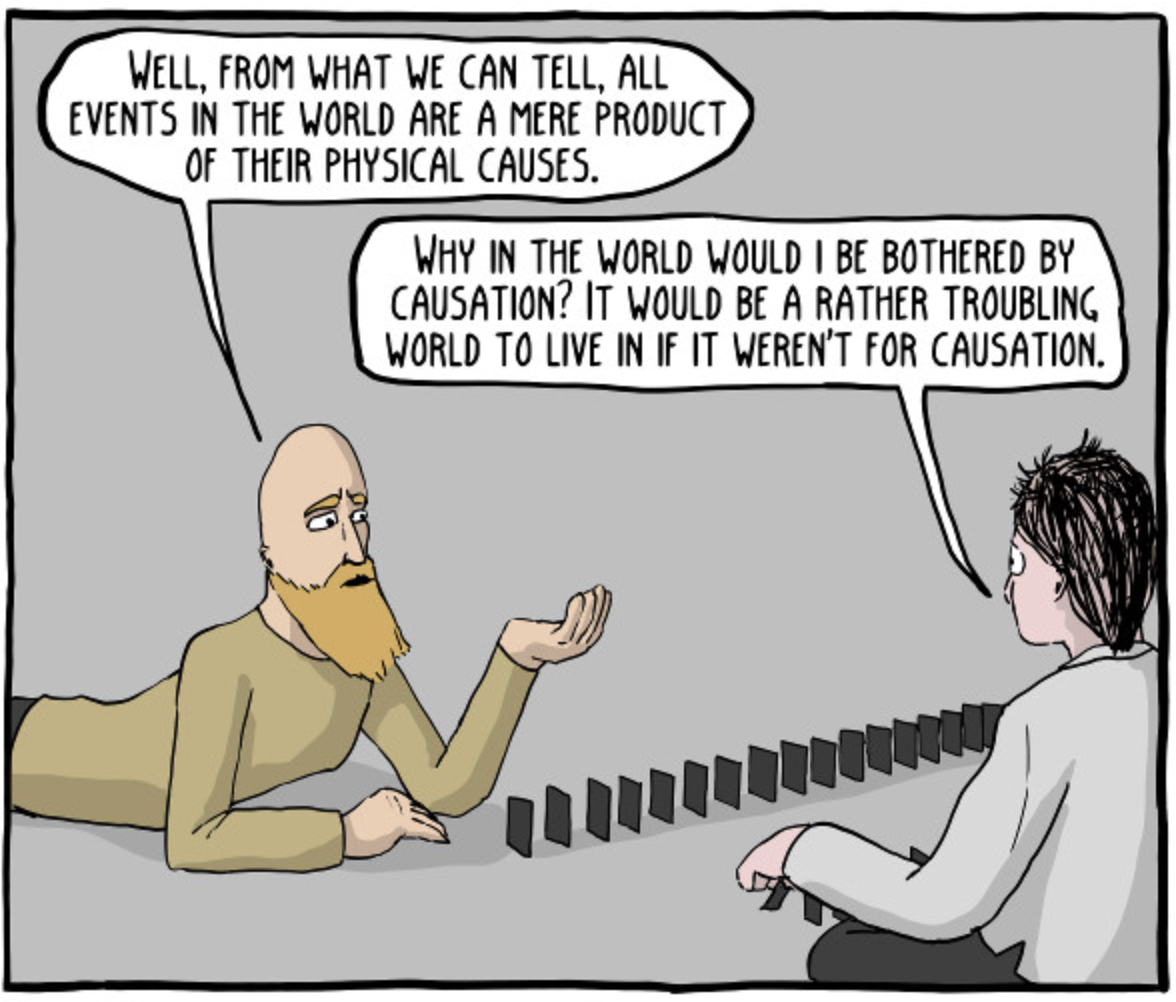

Alongside the fervor for neural networks, there’s been renewed attention given to Bayesian methods for developing machine learning models that can learn from less data and learn in a way that’s more akin to how human beings learn see Josh Tennehbaum. Judea Pearl has also recently re-popularized the use of Bayesian inference and causal models when trying to build intelligent machines.

Bayseian methods remain less used for industrial automation purposes but do hold value if our goal is to build machines that think like humans. One difficulty in finding applied use cases utilizing Bayesian machine learning techniques is that they are not yet as easy to implement (in part because less research has been devoted to this area, comparatively).

See full comic here: http://existentialcomics.com/comic/70

Now that we understand some of the landscape of the methods that are being researched most today, we can start to understand the debate on the direction of that work (and how it differs depending on our goals). In the interest of brevity, I’ll focus on reinforcement learning here.

Reinforcement learning has the potential to allow us to build machines that can accomplish complicated human tasks (it’s deeply implicated in autonomous driving). It’s also useful in informing neuroscience (e.g. this article and others from Jane X Wang). The goal of using this method to build enterprise-ready products is less straightforward as solutions here focus on well-established machine learning methods that can make inferences on short time scales and that can generalize to many real-world unplanned situations. This type of goal is not neatly aligned with methods like reinforcement learning.

A critique of the funding poured into reinforcement learning was brought forth by Gary Marcus last week when he wrote an article criticizing Google’s investment in DeepMind. Part of the debate here centers on the lack of applicable use cases and financial returns on such a large investment in research. Another part stems from a fear that if we don’t start to see some real progress toward AI, despite the hype and massive funding dedicated to this research, we’ll see another “AI Winter”.

Just a few weeks prior to Marcus’ article, Google’s DeepMind released a paper in the journal Nature detailing how they’d developed an algorithm to predict kidney injury. Unfortunately, the study has major flaws in the way the data was chosen, such that the sample used for training consists of mostly white male patients (see here for more). This sample choice severely limits the generalizability of this work to clinical populations and could lead to more skepticism around the applicability of machine learning research for entirely the wrong reasons. However, in this case at least, this is due not to algorithmic limitations per se, but rather to not having a team that is cross-disciplinary enough to spot this major flaw.

This problem is pervasive as machine learning evolves, and lest we cast DeepMind in a shadow, they are one of the biggest contributors to tools and libraries that make reinforcement learning more accessible to those outside big corporations, such as their release of bsuite earlier this week.

We’re seeing progress in all three goals outlined above (though we’re nowhere near building an AGI). That progress relies on a rich combination of the different types of algorithms explained above (as well as others). The fact is that much of the work done in pursuit of one goal will create libraries and artifacts that can be borrowed from those focusing on another goal. In that same vein, as we push for more applicable research (in part to create commercially viable applications to offset the cost of this research), it’s imperative that we collaborate with people across multiple disciplines to ensure what’s being built isn’t only algorithmically excellent but also methodologically sound and avoids bias as much as possible.

A lack of clear definition around the direction of machine learning research can fuel larger paranoia and make room for others not involved in machine learning research to claim a direction. This is illustrated in an opinion piece by Peter Theil, where he argued that AI is a “military technology” and chastised Google for building AI research labs in China. The answer then, as I see it, is not to continue to throw stones across the virtual wall and debate which algorithms or methods reign supreme - especially since we don’t even have a clear end point in mind (are we building a human-like intelligence, or a reasonable customer service call router?). We should instead seek to include those with complementary subject matter expertise and perpetuate the current culture of open science in machine learning.