Nov 21, 2019 · newsletter

Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: A Primer

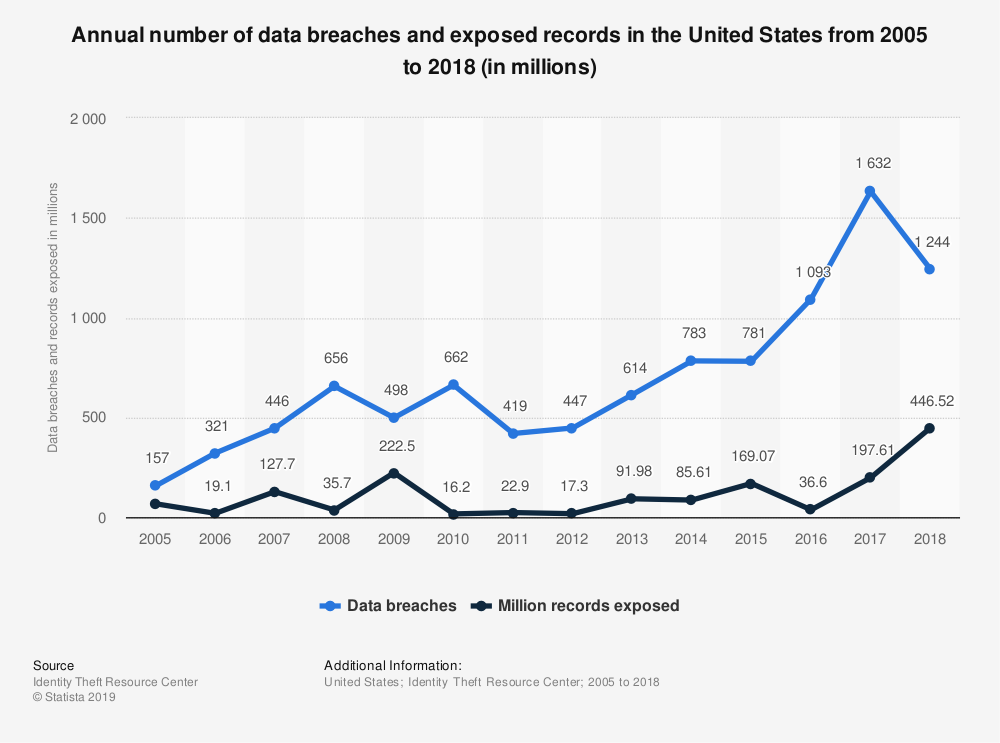

I have a bit of a cybersecurity background, so a year or two ago I started paying attention to how often data breaches happen - and I noticed something depressing: they happen literally 3+ times each day on average in the United States alone! (For a particularly sobering review check out this blog post.) All that information, your information, is out there, floating through the ether of the internet, along with much of my information: email addresses, old passwords, and phone numbers.

Governments, countries, and individuals - with good reason - are taking notice and making changes. The GDPR was groundbreaking in its comprehension, but hardly alone in its goal to shape policy surrounding individual data rights. More policies will pass as the notions of individual privacy and data rights are explored, defined, and refined.

So what does this mean for machine learning?

Machine learning algorithms are known to be data-hungry, with more sophisticated ML models requiring ever more data in order to learn their objectives (caveat: your ML model may be learning some unintentional things, too!). With the need for so much data, what happens to the privacy of data as it is processed through an ML workflow? Can data stay private? If so: how, and at what cost? This article is by no means comprehensive or exhaustive. It is meant to give the reader an introduction to privacy-preserving techniques developed specifically for ML environments. In future articles, I’ll dive deeper into each of these security topics.

But before we can understand security and privacy solutions, we have to understand some of the threats to data privacy imposed in machine learning workflows.

Threats to Data Privacy from Machine Learning

While there are certainly more threat vectors to ML workflows than we’ll cover here, for now we’ll focus on those that specifically adversely affect the privacy of the underlying data used to train an ML model. That means we won’t cover other types of attacks (like adversarial attacks or data poisoning) as these pertain more to the security of the model itself, rather than to the underlying data on which the model was trained.

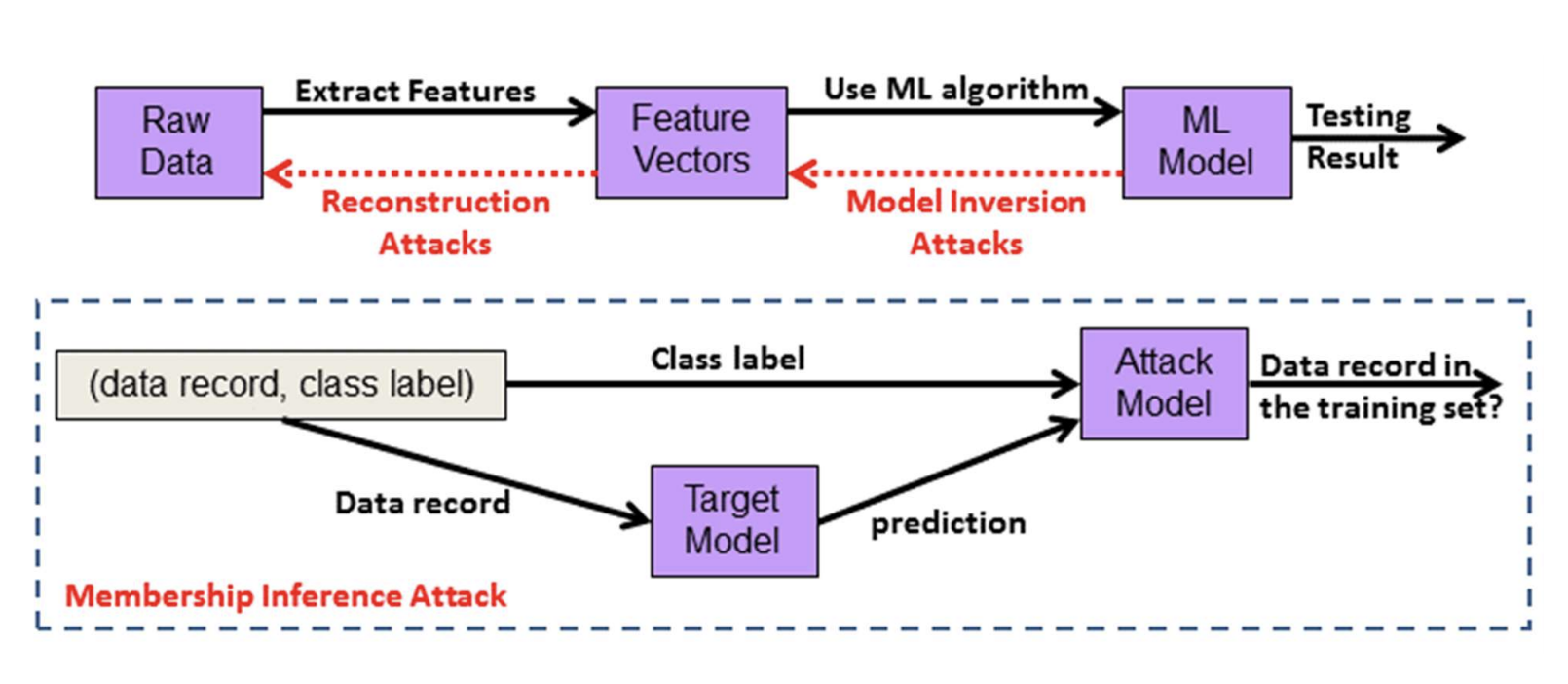

There are three general steps when developing a machine learning application: extracting features from raw data, training a model on the extracted features, and publishing the trained model in order to gain new insights (wouldn’t be much good if the trained model sat unused on a dusty server somewhere!). Privacy concerns lurk at each step in the process. Here we’ll cover three of the most common attacks on data privacy in machine learning.

Threats inherent within the machine learning development cycle.

Source: Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: Threats and Solutions

Threats inherent within the machine learning development cycle.

Source: Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: Threats and Solutions

Reconstruction Attacks

A reconstruction attack is when an adversary gains access to the feature vectors that were used to train the ML model and uses them to reconstruct the raw private data (i.e., your geographical location, age, sex, or email address). For this attack to work, the adversary must have white-box access to the ML model; that is, the internal state of the system can be easily understood or ascertained. Consider, for example, that some ML models (SVMs, KNNs) store the feature vectors as part of the model itself. If an attacker were to gain access to the model they would also have access to the feature vectors, and could very likely reconstruct the raw private data. Yikes!

Model Inversion Attacks

A model inversion attack is one step removed from the above. In this attack, the adversary only has access to the results produced from the trained ML model, not the feature vectors. However, many ML models report not only an “answer” (label, prediction, etc.) but a confidence score (probability, SVM decision value, etc.). For example, an image classifier might categorize an image as containing a panda with a confidence of .98. This additional piece of information - the confidence - opens the door for a model inversion attack. The adversary can now feed many examples into your trained model, record the output label and confidence, and use these to glean what feature vectors the original model was trained on in order to produce those results.

Membership Inference Attacks

This is a particularly pernicious attack. Even if you keep the original data and the feature vectors completely under lock and key (e.g., encrypted), and only report predictions without confidence scores, you’re still not 100% safe from a membership inference attack. In this attack, the adversary has a dataset and seeks to learn which of the samples might have been used to train the target ML model by comparing its output with the label associated with that sample. This type of attack is illustrated in the dashed box in the figure above. Successful attempts allow the attacker to learn which individual records were used to train the model, and thus identify an individual’s private data.

Anonymization is a privacy technique that sanitizes data by removing all personally identifying information before releasing the dataset for public use. Unfortunately, this technique also suffers from membership inference attacks as was demonstrated in the now-infamous Netflix case. The attack is the same as in the ML case: in that instance, researchers used the open-source internet movie database (IMBD) to infer the identities of the anonymized Netflix users.

Privacy-Preserving Solutions

So what are responsible machine learning enthusiasts and practitioners to do? Give up and go home? Obviously not. It’s time to present some solutions! While some of these ideas aren’t particularly new (for example, differential privacy has been around for at least 13 years), developing practical ML applications with these privacy techniques is still a nascent area of research. And while there is not yet a one-stop-shop for ML privacy on the market, this is definitely a space to follow as developments come quickly.

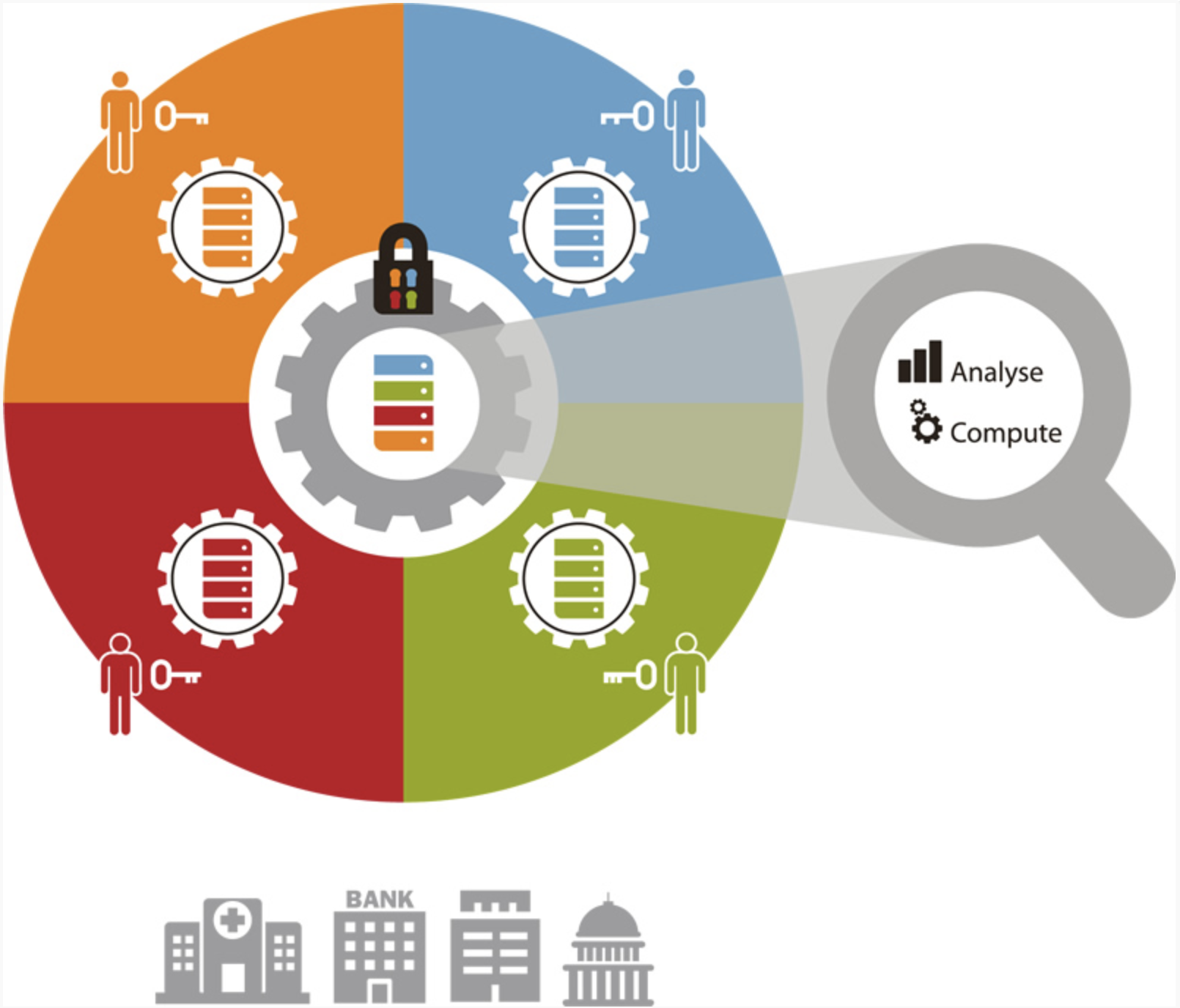

Secret Sharing and Secure Multi-Party Computation

Secret sharing is a method of distributing a secret without exposing it to anyone else. At its most basic, this scheme works by assigning a “share” of the secret to each party. Only by pooling their shares together can they reveal the secret. This idea has been developed into a framework of protocols that make secure multi-party computation (SMPC) possible. In this paradigm, the “secret” is an entity’s private data which is typically secured cryptographically. SMPC then allows multiple entities (banks, hospitals, individuals) to pool their encrypted data together for training an ML model without exposing their data to other members of the party. This type of protection strongly protects against reconstruction attacks.

source

Differential Privacy

To thwart membership inference attacks, differential privacy (DP) was born. DP provides mathematical privacy guarantees and works by adding a bit of noise to the input data in order to mask whether or not a specific individual participated in the database. Specifically, the output will be statistically identical (within a very small tolerance) whether or not an individual’s data was present in the computation. However, the system has limits: every time the database is questioned (output is computed), a bit more privacy is lost. If the adversary is allowed to ask infinitely many questions of the database they could eventually successfully execute a membership inference attack. Thus, setting the “privacy budget” - or how much total information leakage is allowed - is crucial for safeguarding the data.

Homomorphic Encryption

Standard encryption techniques effectively make data completely useless. You can’t glean any information from it; you can’t compute on it; you can’t learn anything from it. That’s the point! It’s private, unless you know the encryption key. But wouldn’t it be great if there was a type of encryption that could keep data private but still allow basic computation without access to the secret key? Turns out, this exists and it’s called homomorphic encryption (HE). This type of encryption allows very simplistic computations to be performed on the encrypted data (addition, multiplication). When combined into more complex series of computations, simple ML models can be built and trained. There are drawbacks, of course - HE is computationally expensive.

Hardware-based Approaches

The methods discussed so far have all relied on algorithms and software to achieve data privacy, but that’s not the only approach. Security for code, data, and access can also be achieved through hardware such as Intel’s SGX processor. Essentially, its a standard CPU with beefed-up security instructions that allow developers to define private regions of memory, called enclaves, in the computer. These memory regions are internally encrypted and, as such, resist modification, reading, or tampering from external users or any processes existing outside the enclave.

Closing Thoughts

There’s a big world of privacy-preserving machine learning out there and this article just scratches the surface. The important take-away is that data privacy is a big deal - and getting bigger each year - as more and more high profile data breaches occur. It’s important to make thoughtful choices about how your ML applications will put privacy into practice. Different ML workflows will require different privacy paradigms, so thinking about this before jumping in is critical. The big questions you should ask of your ML application:

- Who holds the data and what level of security is appropriate?

- Who computes on the data (trains the ML model) and should they have access to the data?

- Who hosts the trained ML model and does it require additional security to prevent inadvertent information leakage?

The answers to these questions will hopefully point you in the direction of one (or more!) of the privacy-preserving solutions presented above.

Here’s to a more secure world!