Nov 15, 2020 · post

Representation Learning 101 for Software Engineers

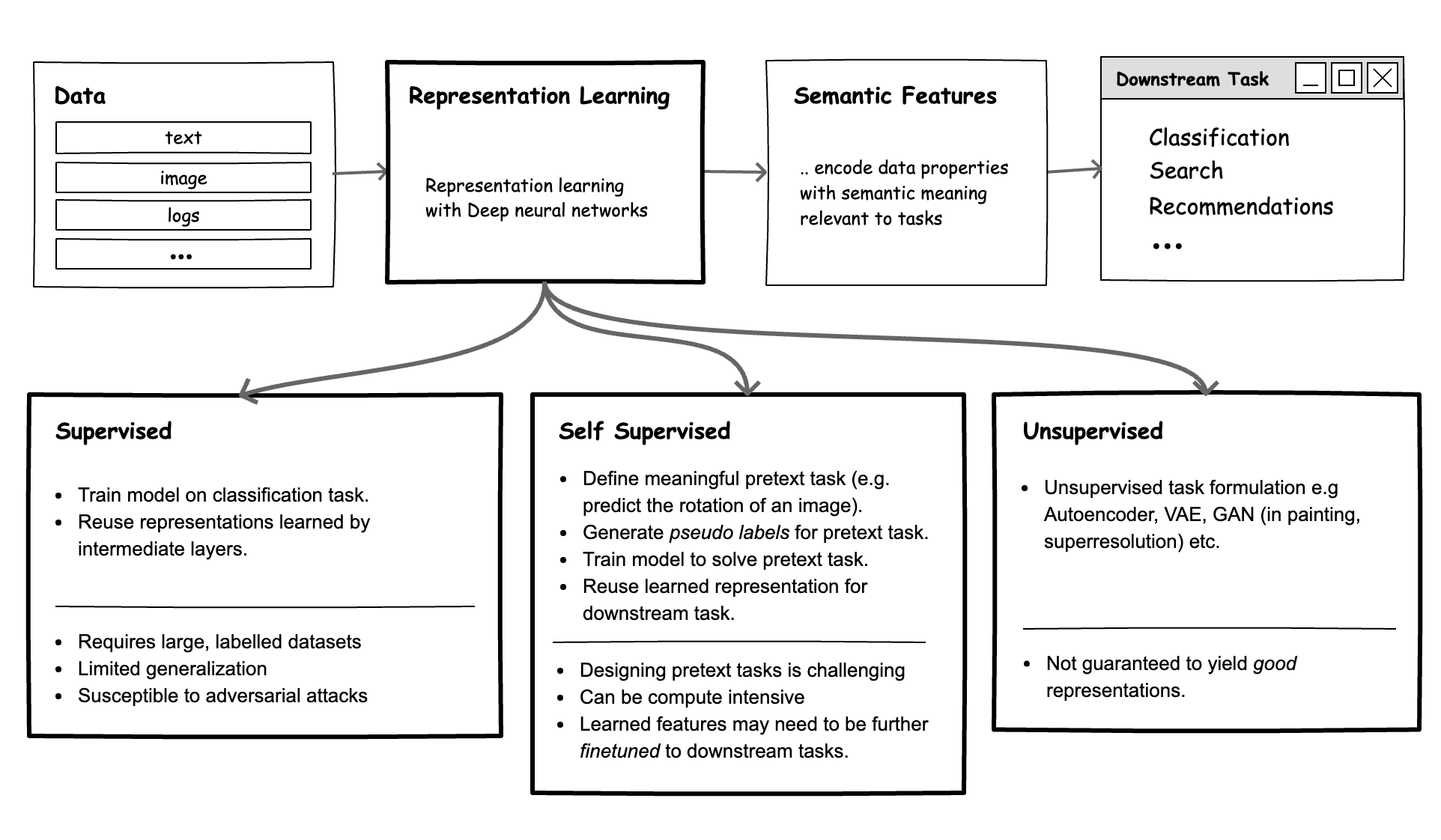

Figure 1: Overview of representation learning methods.

Introduction

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have become a particularly useful tool in building intelligent systems that simplify cognitive tasks for users. Examples include: neural search systems that identify the most relevant results given a natural language or image query, recommendation systems that provide personalized recommendations based on the user’s profile, and few-shot face verification systems.

The performance of many of these systems is gated on their ability to create representations (or features) of data with semantic meaning - numbers that truly encode the meaning of each data point with respect to the current task. For example, suppose a customer has a picture of an outfit they like. To enable the customer to find relevant clothes like it in our database, we need good measures of relevance that compare the user’s picture and all items in the database. Similarly, to recommend the right products to users based on their profiles, we also need high quality measures of relevance e.g., a measure of similarity between a user and all products.

DNN models are the tool of choice in realizing such systems, because they excel at learning semantically meaningful representations. However, across many real-world use cases, these models need to be carefully designed to fit both the task and data.

In this article, we will discuss:

- What representation learning is, and why it’s valuable

- Methods for representation learning

- Learned Representations: how to evaluate good representations and when to use which methods

and share an example of implementation, using supervised representation learning for the task of semantic image search.

Deep Representation Learning: What and Why!

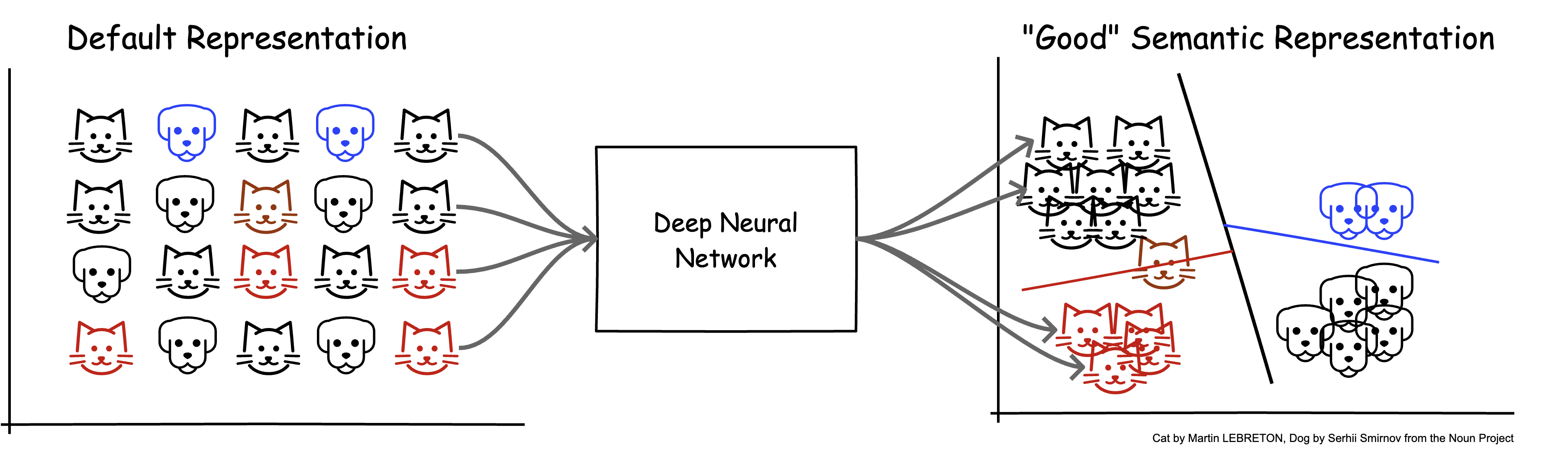

Figure 2: a.) Default representation of data (e.g., raw pixel values) do not encode semantic meaning b.) Features or representations provided by a good DNN model should encode meaning related to the current task (in this case, classification). With this representation, similar data items are closer to each other; the original non-linear problem is now linearly separable, and therefore easier to solve.

Based on the above, we can define deep representation learning as training DNN models that yield numerical representations of data, suitable for solving a set of tasks.

To build intuition on why representation learning is valuable, we can review the question of how humans solve cognitive tasks. In many cases, we rely on heuristics - a set of fairly simple rules relevant to the task. For example, to identify if an image is a cat, we might perform the following checks: does it have four legs, two pointy ears, fur, whiskers, etc.? Based on the presence/absence of these salient features, we might determine with some level of confidence that it is, indeed, a cat.

Similarly, a neural network that succeeds at this same task should allocate its capacity (layers) such that it successfully translates (or disentangles) raw input data (e.g., image pixels) into a set of representations (e.g., eyes, ears, legs, whiskers) that are useful for the task.

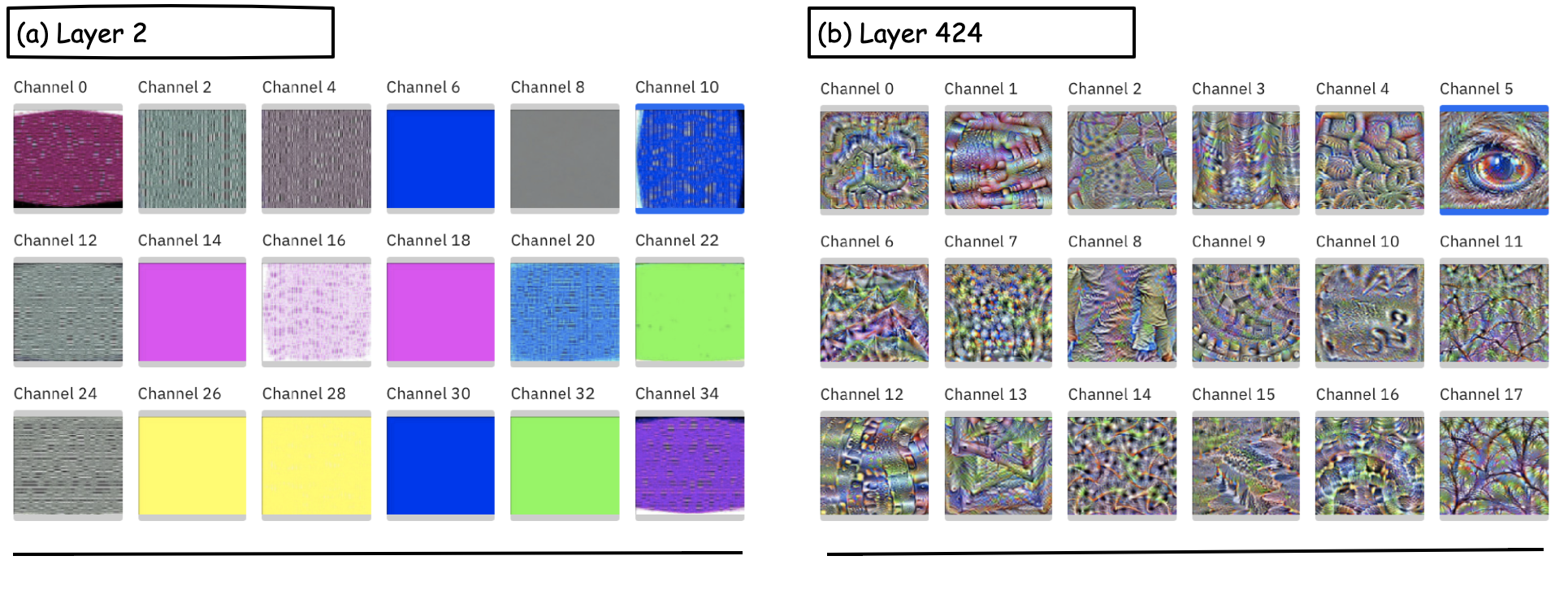

Figure 3: Layers in a pretrained DenseNet121 model. a.) Layer 2 contains neurons that mostly respond to colors and simple textures. b.) Layer 424 contains neurons that respond to more complex, level concepts such as tree patterns and an eye. You can visually explore more representations learned by pretrained models here.

Keep in mind that layers within a DNN are stacked units of computation comprised of weights and bias terms, whose values are learned during training. Thus, if we formulate our training objective carefully, a DNN can yield representations that are then useful for a family of related tasks. Depending on the availability of labeled data, compute capacity, and distribution of data, there are several useful strategies for learning representations.

Methods for Representation Learning

Supervised Learning

When we train a DNN on a supervised learning task (e.g., classification), the training objective naturally yields representations that are useful for solving the task. In practice, this approach takes two main forms:

- Generic Classification: The most common examples of this are the use of models pretrained on the ImageNet dataset (1 million images, 100 classes) and, more recently, the Google BiT model trained on the JFT-300M dataset (300 million images, 18,291 classes)[13]. Extensive experiments have shown that the representations learned by these pretrained models (layers before the final softmax classifier layer) yield representations that are suitable for many other image processing tasks (transfer learning).

Figure 4: A 2D UMAP plot of features extracted using intermediate models constructed from a pretrained EfficientNetB0 model for a set of 200 natural images across 10 classes (arch, banana, Volkswagen beetle, Eiffel Tower, Empire State Building, Ferrari, pickup truck, sedan, Stonehenge, tractor). Given that the salient attributes for this specific set of natural images are high level features (e.g., wheels, doors), we see that the layers closest to the final classifier show the best performance, i.e., clean separation between classes.

-

Metric Learning: Metric learning approaches aim to learn a good embedding space, such that the similarity between samples are preserved as distance between embedding vectors of the sample [9]. To this end, we can train DNN models with loss functions that yield this embedding space. Traditional metric loss functions include contrastive loss [8] and triplet loss [7], which are formulated to minimize intra-class distances and maximize inter-class distances.” One limitation here is that we frequently need to build training data pairs (consisting of positive and negative pairs), which can be challenging in practice. Furthermore, the performance of the model is sensitive to the strategies used for sampling these pairs [10]. To address this issue, variants of the softmax loss function (e.g., large margin softmax [11], angular softmax [12]), optimized for reducing the intra-class variation (i.e., making features of the same class compact) have been proposed, and yield state of the art results, with minimal complexity. Existing research also shows it is valuable to add L2 normalization prior to the softmax loss, as this more explicitly optimizes for cosine similarity [4][10]. Finally, researchers have also explored ensembling (training and combining results from multiple learners) [3] for even better performance, but with drawbacks in system complexity, and additional hyperparameters that need to be optimized.

Note: while much of the academic literature on metric learning focuses on applications in face recognition/verification, they can be adapted to other media modalities.

In general, a supervised approach assumes the availability of large labeled datasets - a requirement that is rarely achievable in practice. It also yields representations that may not generalize out-of-the-box, and may be susceptible to adversarial attacks.

Some applied examples include: Pinterest Pintext [14] - a multitask model trained using engagement data (clicks and repins) as labels (a measure of similarity between text queries); Visual metric learning at Pinterest - in which millions of Pinterest images with labels are used to learn a similarity metric for content-based image retrieval [9], [18]).

Self-Supervised Learning (Pretext Tasks)

In this paradigm, the goal remains to train a supervised learning model, but find creative ways of automatically generating meaningful labels. Historically, this is done by designing pretext tasks - tasks that, if solved, yield semantically meaningful representations as a side effect. Some example pretext tasks used in the image domain include:

- Predicting the angle of rotation (geometric transformations)

- Predicting if two images with transformations (e.g., color transformations, or random crops) are the same (constrastive) [2]

- Predicting if two image patches come from the same image (image jigsaw puzzles) [16]

- Predicting the order of image frames from a video sequence (temporal)

For an extensive treatment on methods for self-supervised visual feature learning, see the survey paper [15].

Note that the self-supervised approach (commonly known as pretraining) is also well-known in the NLP field:

- Predicting the next word from a sequence of words

- Predicting the masked word in a sentence

- Given two sentences, predicting if one follows the other

A good pretext task is one which requires semantic understanding (or knowledge of important patterns) to solve (as seen in the examples above). The pretext task also takes advantange of known properties of the data in generating a training dataset; e.g., for the task of predicting the angle of rotation for an image, we can apply rotation transforms to images, and the labels are the rotation angles. If we construct pretext tasks that are inherently meaningful, then we can provide some signal (impose constraints) for the network to build notions of meaning. The harder the task, the more relevant the representations learned [16]. In general, a model is trained to solve the pretext task on a large dataset of unlabeled images, and the representation it learns is transferred to other downstream tasks.

Advances in self-supervised representation learning are particularly exciting. Recent research, which explores a contrastive formulation for pretext tasks, shows that self-supervised methods can achieve results at par with supervised learning! For example, SwAV[2] is only 1.2% below the performance of a fully supervised model.

Unsupervised Learning

In some situations, it may be challenging to design good pretext tasks (e.g., data augmentation strategies or transforms are not meaningful, sampling negative or positive pairs is hard, etc.). For these situations, fully unsupervised methods can be explored. Many of these methods fall under the class of generative models, where the objective is to model a data distribution that can be subsequently sampled. Some examples of these models include an autoencoder, denoising autoencoder, VAE, and GANs (generation, inpainting, superresolution, colorization)[15]. While there is no explicit pretext task, the training objective still requires the model to disentangle input into salient features which may sometimes have semantic meaning. Strictly speaking, however, unsupervised learning is uncertain, and does not provide guarantees that the representations learned are particularly good.

Learned Representations: Evaluation and Use

Evaluation

How do we know if we have good representations? How can we verify that a model has learned the underlying causal structures with respect to a task? This is hard to mathematically quantify, and historically has been evaluated based on downstream task performance (e.g., image classification, semantic segmentation, object detection, and action recognition) [15]. For example, representations learned using any of the methods listed above can be evaluated by using them as input for a linear logistic regression classifier on a downstream task. There have also been some interesting ideas put forth on ways to improve learned representations using clustering and pseudo labels; see [16], SwAV[2].

When to Use What? Practical Considerations

Selecting an approach for representation learning is largely a tricky excercise in balancing effort (compute, time) and expected quality of representations. On the one hand, fully supervised methods yield the best performance for a specific task (e.g., see results from Pinterest [9]), but require the effortful curation of very large labeled datasets. On the other hand, fully unsupervised methods require no labeling effort, but do not provide strong guarantees for learning robust representations, resulting in varied performance.

The following high level notes are perhaps useful:

- Pretrained model baselines: Where possible, begin explorations using pretrained models. This may involve directly using features from a pretrained model (as seen in the next section) or finetuning the pretrained model, using a small amount of labeled data (transfer learning). Of course, this approach only works if the target task data distribution is similar to the data used to create the pretrained models.

- Self-supervised baselines: Where a large amount of unlabeled data exists, self-supervised methods are particularly useful. Explore pretext task strategies pertinent to the data in learning an initial set of representations, that can then be finetuned using pseudo labels [16] and/or a small amount of labeled data.

Semantic Image Search with Pretrained Neural Network Models in Tensorflow

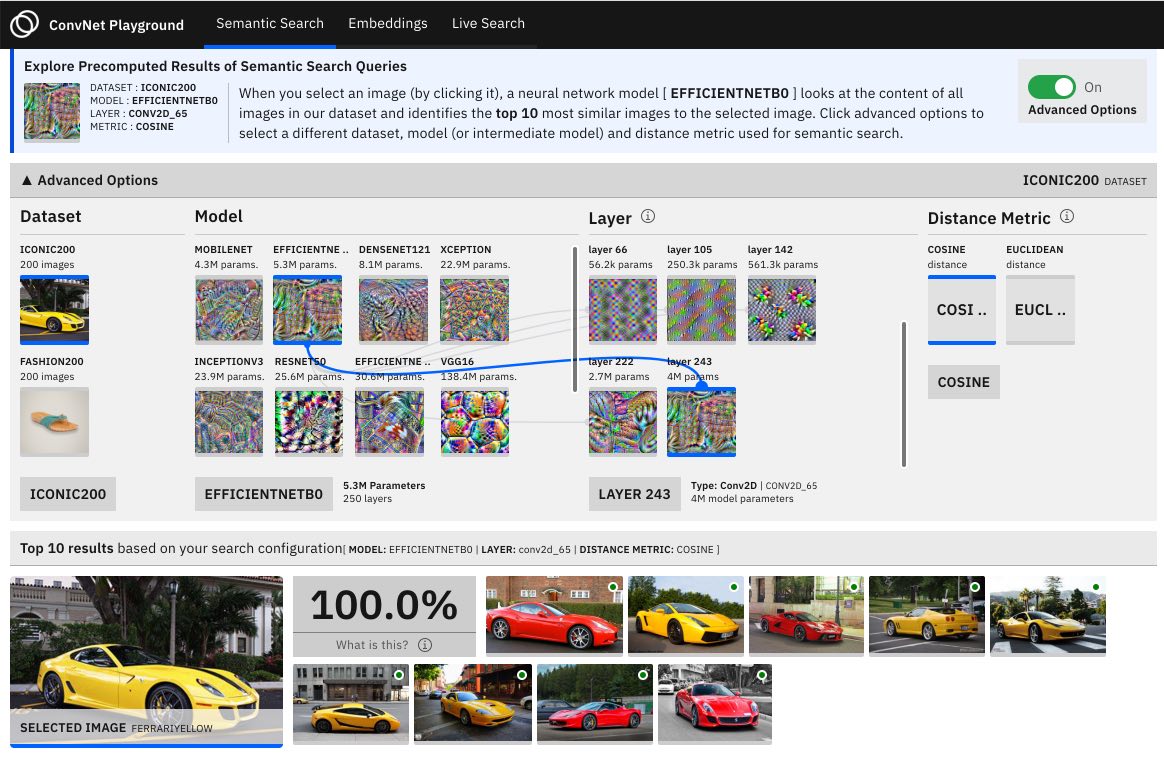

Figure 5: Screenshots from a web application we built which allows you to delve into semantic search query results, explore a visualization of embeddings, and perform live search. (Full source code here.)

To demonstrate how representations can be used for a concrete task, let us consider the task of semantic image search (also known as content-based retrieval, image retrieval, or reverse image search). We define semantic search as follows:

Here is a simplified implementation of semantic search outlined as a three-step process:

- Feature Extraction: First, a pretrained CNN model is used to extract features (vector representation) for each image in the dataset. Note that, depending on the layer within the model, we may have vectors of varied sizes. In the example snippet below, we load an EfficientNetB0 model from the keras model zoom, and use its last layer before (

include_top=False) its linear classifier as a feature extractor. This yields a vector of size(1, 7, 7, 1280)or62720when flattened, per image.

|

|

- Indexing: Once we have our feature vectors for each image, we need infrastructure ( an index) that enables us to efficiently store these representations, such that we can subsequently run search queries.

As the size of the dataset becomes larger, two challenges emerge. First, a significant amount of space is needed to store vectors of size

62720each, for millions of images. Second, it becomes computationally slow to exhaustively search over all images in our dataset (i.e., computing a similarity distance metric between the query and all dataset images and sorting results by distance). The first challenge can be addressed by applying transforms (e.g., dimensionality reduction, quantization) to our feature vectors. The second challenge can be addressed by using approximate nearest neighbour (ANN) methods [17]. Both of these solutions, while practical, result in some accuracy trade off. In the example below, we use the FAISS library which implements both exhaustive search and ANN search, as well as supports dimensionality reduction and quantization. (For a comparison of methods and libraries for ANN, see this blog post.)

|

|

- Search: Finally, to return results for a search query, we retrieve the precomputed distance values between the searched image and all other images, sorted in the order of closest to farthest.

|

|

Full source code for the steps above is provided here.

Conclusions

This article provides a high level overview of methods for representation learning and a simplified example of how good representations extracted using pretrained models can be used for a downstream task such as semantic image search. The reader is encouraged to explore the references provided for additional details on the theory/implementation for the methods discussed.

References

[1] Bengio, Yoshua, Ian Goodfellow, and Aaron Courville. Deep learning. Vol. 1. Massachusetts, USA, MIT press, 2017. https://www.deeplearningbook.org/contents/representation.html

[2] Caron, Mathilde, et al. “Unsupervised Learning of Visual Features by Contrasting Cluster Assignments.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020).

[3] Opitz, Michael, et al. “Deep Metric Learning with BIER: Boosting Independent Embeddings Robustly.” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence (2018).

[4] Ranjan, Rajeev, Carlos D. Castillo, and Rama Chellappa. “L2-constrained Softmax Loss for Discriminative Face Verification.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.09507 (2017).

[5] Fefferman, Charles, Sanjoy Mitter, and Hariharan Narayanan. “Testing the Manifold Hypothesis.” Journal of the American Mathematical Society 29.4 (2016): 983-1049.

[6] Nguyen, Binh X., et al. “Deep Metric Learning Meets Deep Clustering: An Novel Unsupervised Approach for Feature Embedding.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.04091 (2020).

[7] Hoffer, Elad, and Nir Ailon. “Deep metric learning using Triplet network.” International Workshop on Similarity-Based Pattern Recognition. Springer, Cham, 2015.

[8] Chopra, Sumit, Raia Hadsell, and Yann LeCun. “Learning a Similarity Metric Discriminatively, with Application to Face Verification.” 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR'05). Vol. 1. IEEE, 2005.

[9] Zhai, Andrew, and Hao-Yu Wu. “Classification is a Strong Baseline for Deep Metric Learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.12649 (2018).

[10] Wang, Feng, et al. “Additive Margin Softmax for Face Verification.” IEEE Signal Processing Letters 25.7 (2018): 926-930.

[11] Liu, Weiyang, et al. “Large-Margin Softmax Loss for Convolutional Neural Networks.” ICML. Vol. 2. No. 3. 2016.

[12] Liu, Weiyang, et al. “Sphereface: Deep Hypersphere Embedding for Face Recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017.

[13] Kolesnikov, Alexander, et al. “Big Transfer (BiT): General Visual Representation Learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.11370 6 (2019).

[14] Zhuang, Jinfeng, and Yu Liu. “PinText: A Multitask Text Embedding System in Pinterest.” Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 2019.

[15] Jing, Longlong, and Yingli Tian. “Self-supervised Visual Feature Learning with Deep Neural Networks: A Survey.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2020).

[16] Noroozi, Mehdi, et al. “Boosting Self-supervised Learning via Knowledge Transfer.” Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018.

[17] Johnson, Jeff, Matthijs Douze, and Hervé Jégou. “Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs.” IEEE Transactions on Big Data (2019).

[18] Zhai, A., Wu, H. Y., Tzeng, E., Park, D. H., & Rosenberg, C. (2019, July). Learning a Unified Embedding for Visual Search at Pinterest. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (pp. 2412-2420).