May 26, 2021 · post

Deep Learning for Automatic Offline Signature Verification: An Introduction

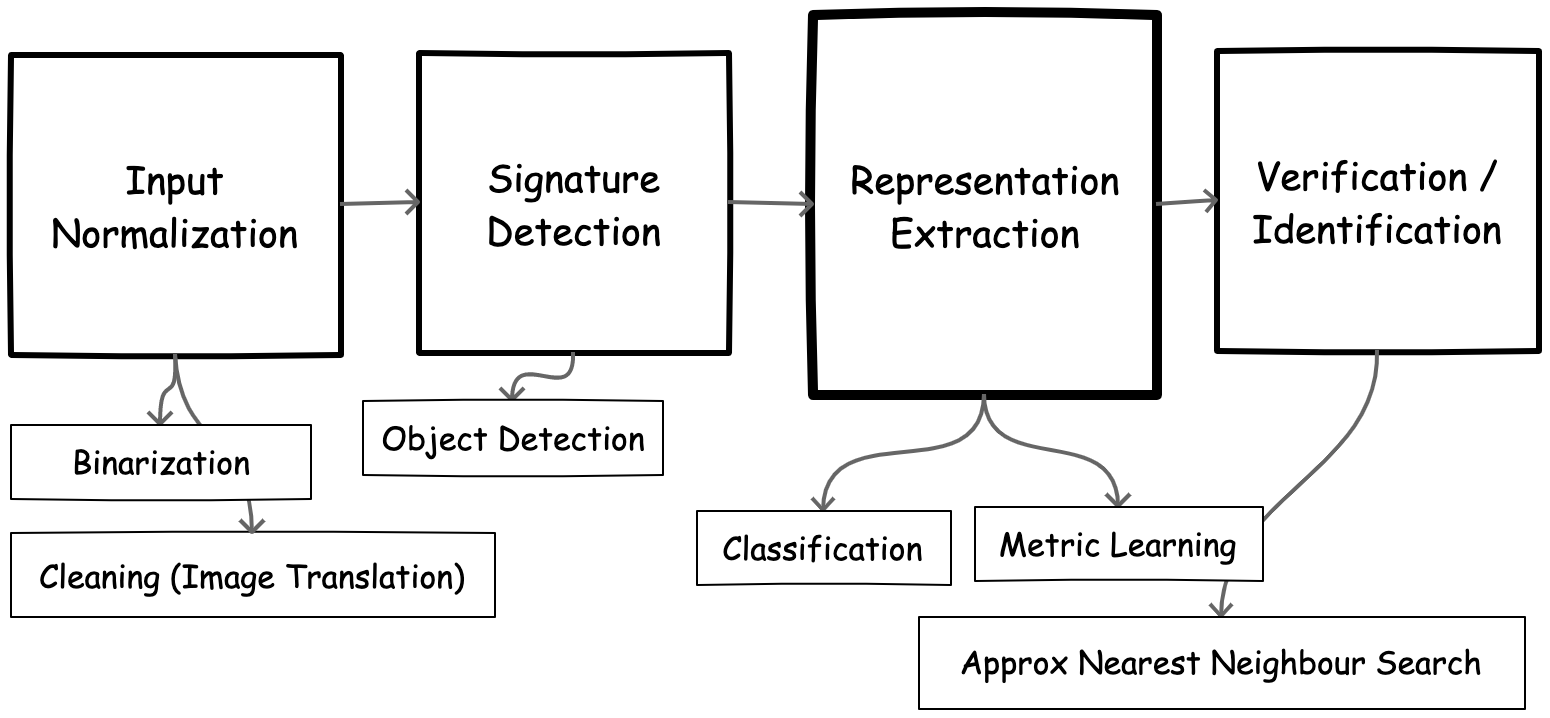

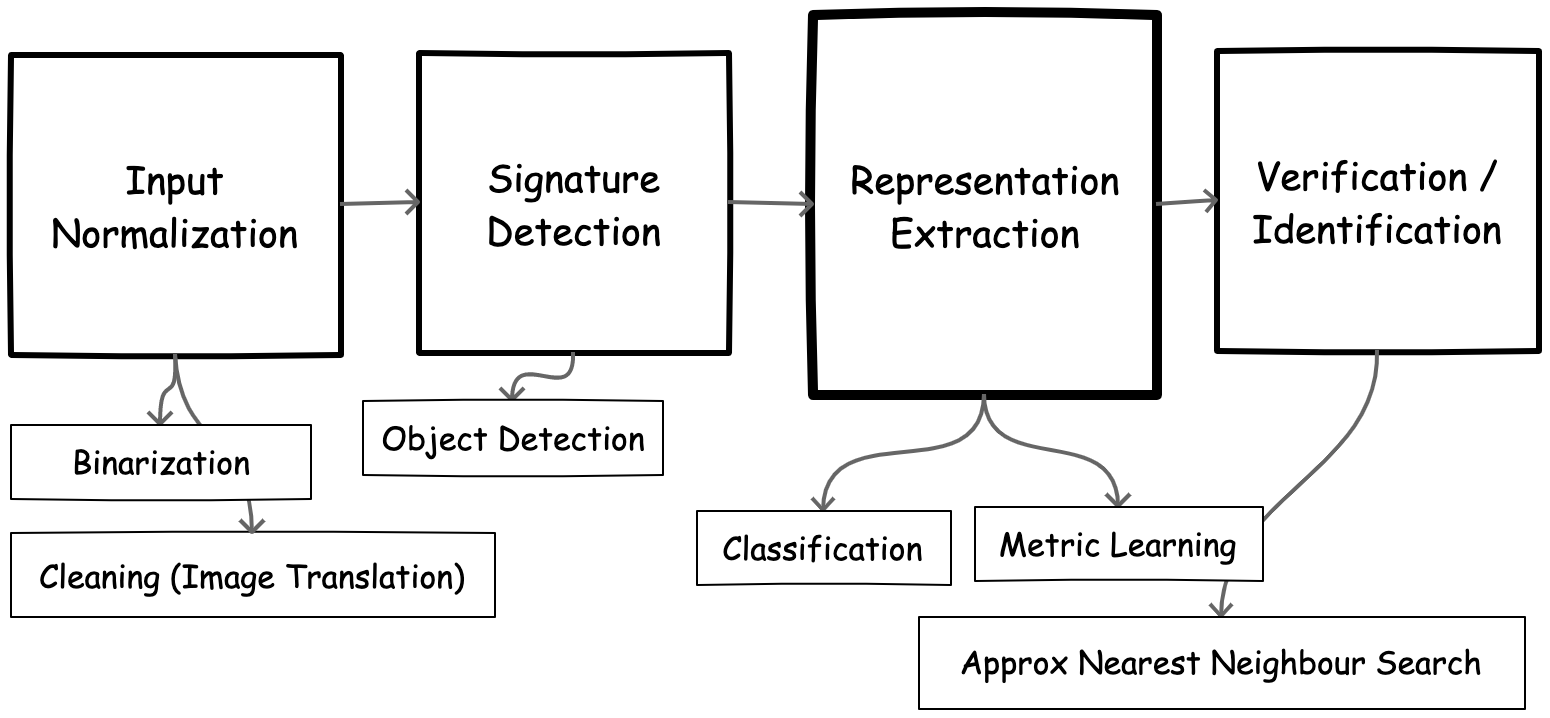

Figure 1. A summary of tasks that comprise the automatic signature verification pipeline (and related machine learning problems).

Given two signatures, automatic signature verification (ASV) seeks to determine if they are produced by the same user (genuine signatures) or different users (potential forgeries). This process, which has been traditionally performed by humans, can be tedious and almost impossible to scale without the use of automatic verification tools. To solve this task, we need a system that, at a high level, can produce measures of similarity between a pair of signatures. We can then exploit this measure of similarity in verifying or matching signatures - i.e., similar signatures are likely genuine; dissimilar signatures are likely forgeries. Given the complex requirements of this problem (understanding the content of images), deep learning models which have excelled in similar perception tasks are a good candidate tool of choice.

In practice, solving the signature verification task requires solving a set of adjacent subtasks (see Figure 1 above). Images of signatures may come in various colors, shapes, rotations, and scale transformations which we need to account for (normalization). They may be located in arbitrary parts of a document and might be occluded with text, stamps, or background noise (detection and cleaning). Once we have localized and cleaned our images, we then have to extract representations using appropriate methods, and efficiently match them against an existing database of known signatures.

In this post, we will:

- Provide an overview of signature verification: what it is and why it is important

- Discuss challenges with automatic signature verification

- Frame signature verification tasks as machine learning problems

This post is the first in a series of posts that will discuss the broader agenda of effectively applying deep learning to the task of signature verification.

Signature Verification: What and Why?

Signature verification falls within the broader field of user biometrics: capturing unique user data, such as behavioural traits (e.g., voice, handwritten signature, typing patterns) or physiological traits (e.g., fingerprints, face, iris, etc). These traits can then be used for security applications, such as identification (matching a user sample to a dataset of samples) and verification (matching a user to a claimed or known identity sample).

The problem of automatic signature verification is commonly modeled as a verification task: given a learning set

$D$, that contains genuine signatures from a set of users, a model is trained. This model is then used for verification: a user claims an identity and provides a query signature$x_{new}$. The model is used to classify the signature as genuine (belonging to the claimed individual) or forgery (created by someone else) 1

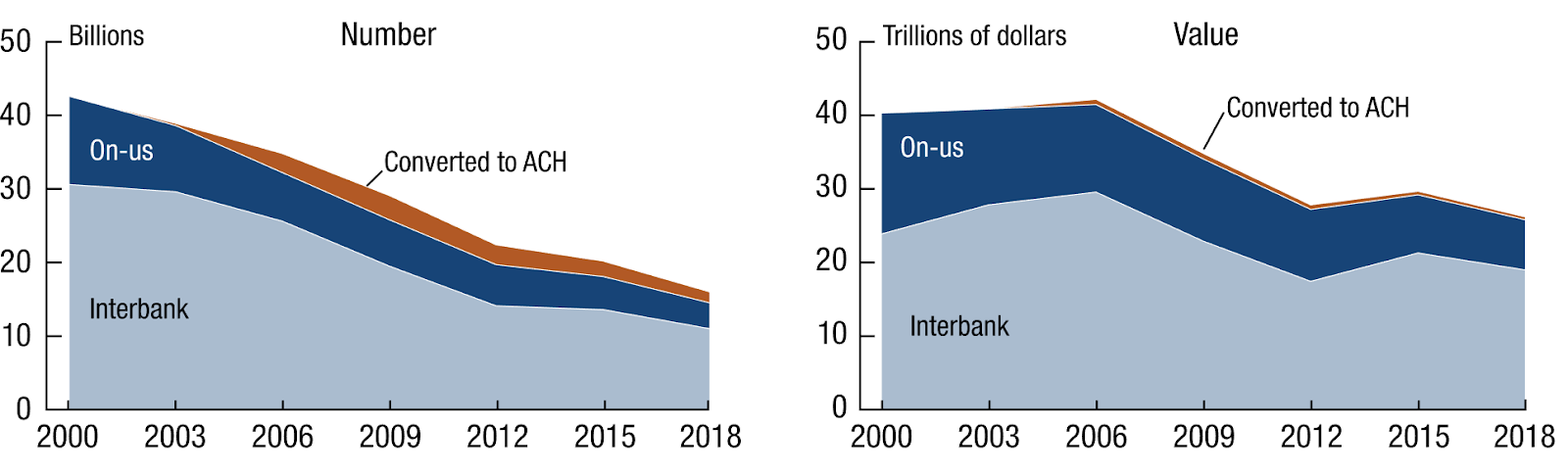

While the overall use of physical documents that contain signatures will likely be reduced as many platforms become digitized, handwritten signatures remain ubiquitous, as they are easy to collect, non-invasive, and useful across multiple daily activities. According to a 2019 study by the US Federal Reserve Payments 2 on checks, an estimated 14 billion checks were issued, with an estimated value of $26.8 trillion. While this represents an 8.2% decline in overall number of checks compared to the previous year, it still indicates a fairly large amount of check transactions. In addition, the rate of digitization varies across locales, with many companies maintaining support for both digital and physical signatures as a physical failsafe, resistant to digital attacks.

Figure 2. Trends in checks written. 14 billion checks were written in 2018 in the United States. (Image Source)

Relevant Terminology

Before we proceed, let’s define a few related concepts in the area of signature verification.

Online vs Offline Signatures

Signatures may be termed as online or offline depending on how signature data is captured. 1 “Online signatures” refers to the capture of signatures using digital devices (e.g., pressure-sensitive tablets, cameras, etc.) and may encompass a wide set of features (such as stroke sequence, pressure, timing, pen inclination, etc.) recorded during the creation of the signature. On the other hand, “offline signatures” are recorded signatures (e.g., scans of signatures on paper) that are subsequently processed.

While online signatures have richer features and are therefore easier/more accurate to verify, they are also expensive to capture. In addition, many use cases or regions do not have access to specialized digital data collection platforms; those with some digital capabilities may fall to passwords. Offline signatures are easier to capture and more ubiquitous, but retain significantly fewer distinguishable features, and hence are harder to verify.

In this work, we will be focusing on offline signature verification, due to its broad applicability in society today.

Skilled vs Unskilled Forgeries

Signature forgeries can be classified into two categories depending on the information available to the forger. Unskilled forgeries represent situations where the user has very little or no information on the user. For example, the forger may produce a random signature, or have access to the genuine signer’s name and offer their own signature of the same name. Skilled forgeries have access to more information - the user’s name and signature samples - and time to practice the reproduction of signatures. In general, skilled forgeries are harder to detect compared to unskilled forgeries, especially in the offline paradigm.

Use Cases

Signature verification is useful across many domains. Let’s explore a set of common use cases.

Banking Check Signature Verification

Banking institutions typically have to verify that a submitted check was authorized by the associated account owner. To achieve this, they rely on matching the signature in the check to a signature they have on file for the account owner.

Administrative Documents

Formal administrative documents such as memos, letters, memorandas, etc. frequently bear the signature of their authors as a proof of authorship. In some cases, it is useful to automatically verify these signatures.

Legal Contracts

Legal contracts (e.g., the sale or lease of property) typically become binding with the provision of signatures from each participating entity. Across the lifetime of these contracts (extensions, renewals, suspensions events, etc.), it may be useful to ensure that the expected parties are privy to each of these events and their identities verified.

Beyond security applications, ASV opens up new opportunities for organisations seeking to automatically group, catalog, and search their documents based on signatures or identities (e.g., “show me all documents signed by a given entity”).

Challenges with Automatic Signature Verification

While ASV is useful, there are several issues that make the task particularly challenging.

High Intra Class Variability

A single signer may sign their own signature in different ways, leading to high variability within genuine signatures produced by a user. Signatures across sessions can differ - and even within the same session, signatures may vary due to fatigue. This makes the task of detecting skilled forgeries particularly challenging.

Supporting Writer-Independent Verification Methods

One way to account for high intraclass variability is to build writer-specific solutions that learn variations for each signer. However, this approach does not scale well, given the requirement to assemble extensive data for each user. Thus, signature verification methods must be writer-independent: they must learn representations that discriminate across writers, generalize well to new types of writers, and not depend on any writer-specific features. This makes for a rather challenging problem overall.

Data Quality Issues

Training data for machine learning models is frequently not available in a standardized usable format. For example, signatures in the wild may have noisy background text or stamps, be occluded, be located at arbitrary portions of a document, or have arbitrary scale, rotation, or color transforms applied. These issues can degrade verification accuracy, and need to be addressed upfront.

Data Availability Issues

There are not many public datasets for the task of signature verification. In addition, signatures are sensitive private PII data, making it more challenging to curate, share, or use a dataset for the ASV task. In cases where these datasets exist, privacy laws and regulations (e.g., GDPR) may preclude their use.

Framing Signature Verification as a Machine Learning Problem (Representation Learning)

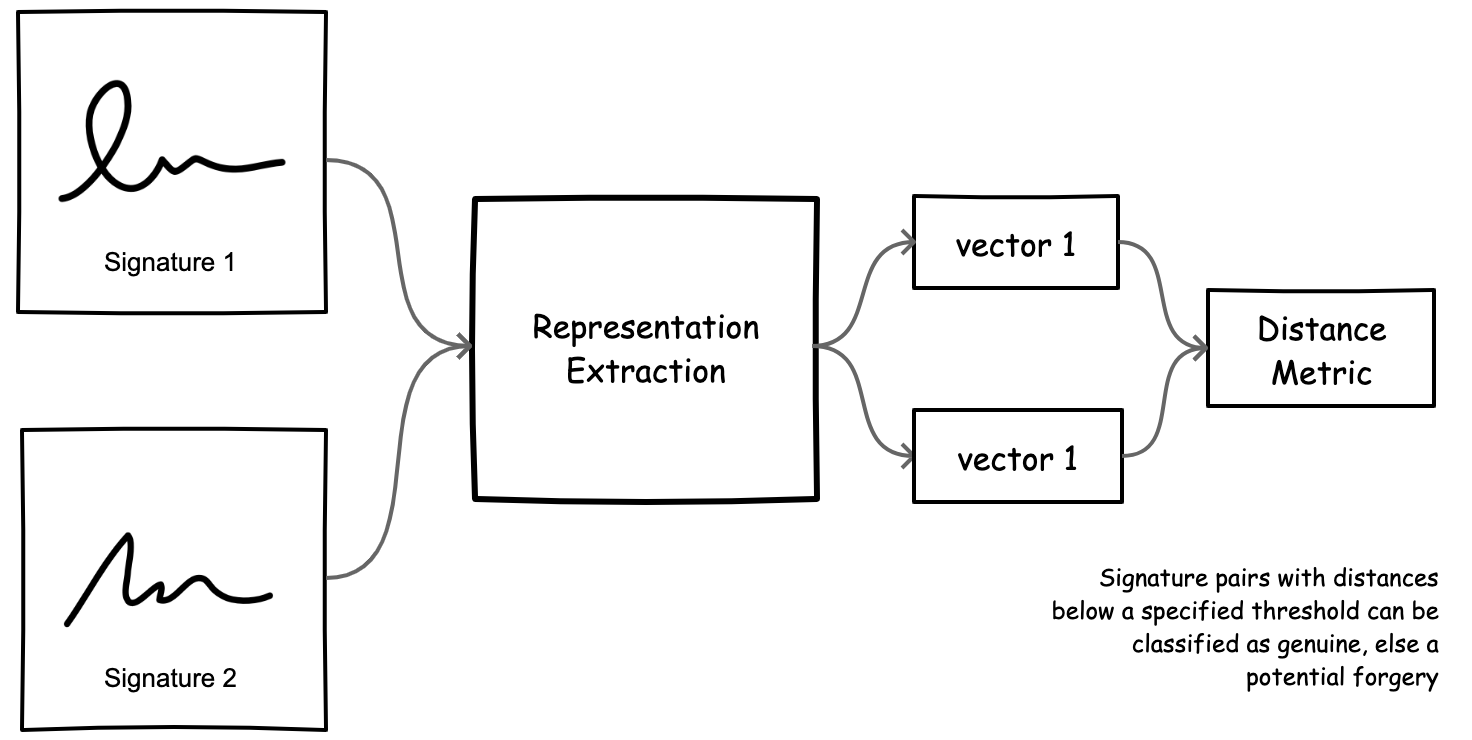

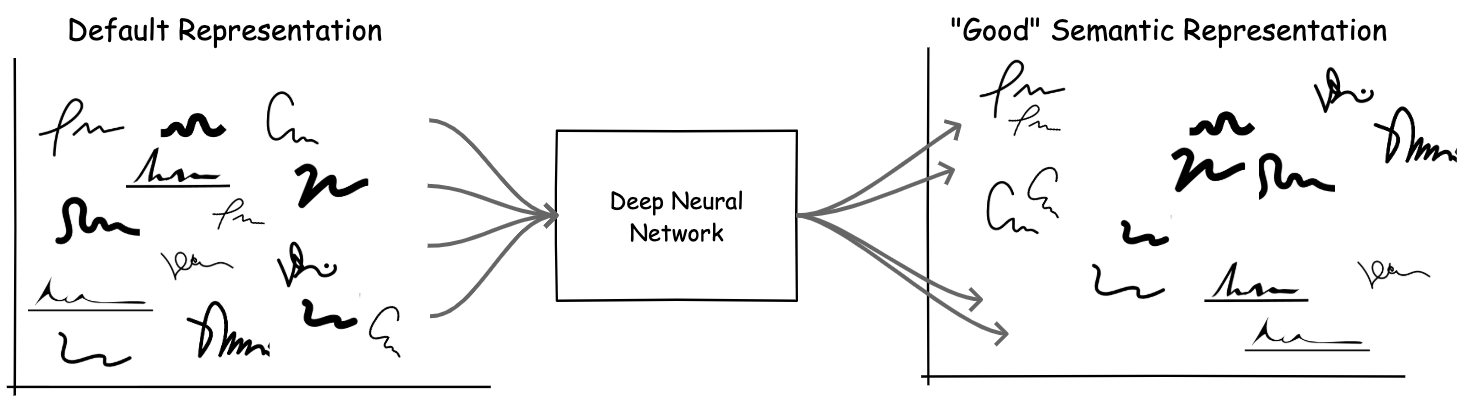

At its core, we can cast signature verification as a representation learning problem, where we train a model that yields semantically meaningful representations of signatures such that vectors for similar signatures are close and dissimilar signatures (likely forgeries) are far apart, using some distance metric.

Figure 3. We can treat signature verification as a representation learning task, where we train a model that outputs semantically meaningful representation vectors for signature images.

However, in practice, signature verification typically entails multiple subtasks that need to be addressed before and after we obtain semantic representations of each signature. These tasks include input normalization, signature localization, representation extraction, and matching/verification.

Figure 4. A summary of tasks that comprise the automatic signature verification pipeline (and related machine learning problems).

Input Normalization

Offline signature images can be noisy. More importantly, they can contain spurious information that might cause a machine learning algorithm to utilize features that do not generalize to new test distributions (e.g., background color of images, stroke color, marks, or ticks that might appear in a subset of training data, etc.). To address this, input images should be normalized. In our experiments, we explored a three-step process, following existing ASV research 1: grayscale conversion to reduce color channels, image binarization using a thresholding method, and cleaning (removal of background artifacts such as text, rubber stamps, etc.).

Note that cleaning can be framed as an image translation problem, where we translate from a dirty image to a clean image, using models such as Autoencoders and GANs (e.g., cycleGANs3). Also note that in other domains (e.g., natural images), color and some types of noise may be beneficial to accurate classification, but are more likely to contribute biases in this use case.

Signature Detection

Documents containing signatures may be of arbitrary sizes and structure, and the location of signatures in these documents may vary. This task (also referred to as signature extraction 1), focuses on identifying the location of each signature, given a document. In this work, we will frame this task as an object detection machine learning (ML) problem where an ML model outputs a list of bounding boxes for signatures, given an image.

Representation Extraction

This task explores the extraction of semantic features (aka representations or embeddings) for signature images. As mentioned earlier, we can cast this task as a representation learning task, where our goal is to attain a model that yields semantically meaningful vector representations of signature images. In theory, this model can be achieved via supervised, semi-supervised, or unsupervised methods.

For an extensive treatment of these areas, see our previous article on methods for representation learning.

Figure 5. a.) Default representation of data (e.g., raw pixel values) do not encode semantic meaning. b.) Features or representations provided by an appropriate DNN model should encode meaning related to the current task (in this case, signature similarity). With this representation, similar data items are closer to each other in the embedding/representation space; the original non-linear problem is now solvable by computing similarity distance metrics.

In this work, we will explore how supervised methods can be used as feature extractors. Specifically, we will evaluate the performance of features extracted, using a pretrained classification model and a metric learning model.

Note: While we are focusing on deep learning approaches for representation extraction, it is important to note that these representations may also be hand crafted features. See 1 for additional references on non-deep learning techniques like SIFT, SURF, or HOG. While hand-crafted features may be relatively fast to compute, they have been shown to be less performant compared to features/representations learned by deep neural networks.1

Ideally, a good representation should be robust to rotation, scale, and other transformations.

Matching & Verification

Assuming we have come up with a representation space that appropriately encodes semantic similarity for each signature, we can then explore verification and identification tasks via a set of simple steps:

- Verification (user claims an identity and provides a signature)

- Retrieve signature representation for claimed identity

- Compute representations for provided signature

- Compute similarity between retrieved and computed signatures. If similarity score lies above a defined threshold, we can classify as genuine or otherwise.

- Identification (user provides a signature with which we would like to identify them)

- Compute representation for provided signature

- Compute similarity score between the provided signature and a precomputed representation database of known identities. This can be modeled as an approximate nearest neighbour search 4 problem, and we can quickly identify the signature in our database that is closest to the provided signature.

Verification (matching two signatures) can be relatively fast, while identification (matching a signature to an arbitrarily large dataset) can be more compute intensive. To enable identification, we can rely on approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search tools like Annoy 5, FAISS 6, and ScaNN 7.

Conclusion

In this post, we have provided an overview of automatic signature verification, use cases and challenges, and how ASV can be framed as a machine learning (deep learning) problem. We have also outlined a list of subtasks that need to be solved in order to implement signature verification in practice: normalization, detection, representation extraction, and matching.

However, there are still several open questions regarding the implementation of an ASV pipeline. How might we design a compelling and strong baseline? Are pretrained CNN models good baselines? How do we evaluate an ASV method? How do we implement each of the subtasks in Python?

In our next two posts, we will address these questions, as well as results from our experiments in implementing each of these tasks.

References

-

Hafemann, Luiz G., Robert Sabourin, and Luiz S. Oliveira. “Offline handwritten signature verification—literature review.” 2017 Seventh International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA). IEEE, 2017. ↩︎

-

Federal Reserve Payments Study on checks, 2019 https://www.frbservices.org/news/research.html#19 ↩︎

-

Zhu, Jun-Yan, et al. “Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks.” Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2017. ↩︎

-

Nearest neighbor search, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nearest_neighbor_search ↩︎

-

Annoy - a C++ library with Python bindings to search for points in space that are close to a given query point https://github.com/spotify/annoy ↩︎

-

FAISS - a library for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors https://github.com/facebookresearch/faiss ↩︎

-

ScaNN - a method for efficient vector similarity search at scale. https://github.com/google-research/google-research/tree/master/scann ↩︎