Sep 20, 2021 · post

How (and when) to enable early stopping for Gensim's Word2Vec

The Gensim library is a staple of the NLP stack. While it primarily focuses on topic modeling and similarity for documents, it also supports several word embedding algorithms, including what is likely the best-known implementation of Word2Vec.

Word embedding models like Word2Vec use unlabeled data to learn vector representations for each token in a corpus. These embeddings can then be used as features in myriad downstream tasks such as classification, clustering, or recommendation systems. Gensim’s documentation and tutorials are sufficient for straightforward applications, e.g., training on a corpus of documents composed of plain text. But they don’t cover what to do if your use case is more complex, like how to choose the number of training epochs or other hyperparameter values. This is especially crucial if you’re trying to learn vector representations for non-natural language tokens, e.g., learning embeddings for products or users or books or music. And what does early stopping have to do with any of this?

In this post, we’ll first cover why and when you should and shouldn’t do early stopping with Gensim’s Word2Vec, and we’ll finish up with how to do it with code. Because we’re no fun, let’s start with the “don’t” before getting to the “do"s.

Don’t use early stopping to prevent overfitting

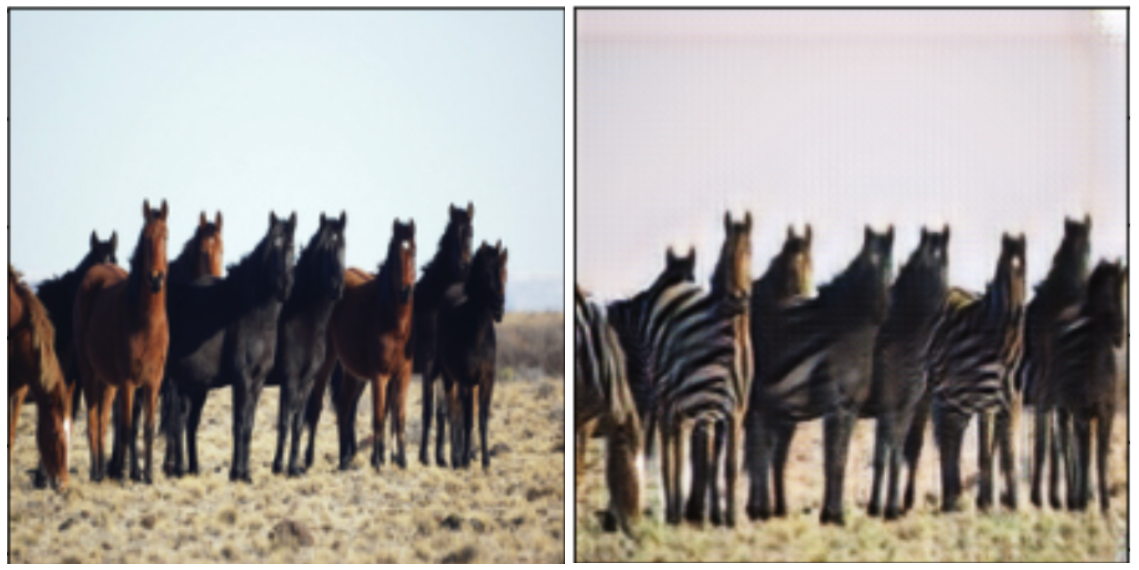

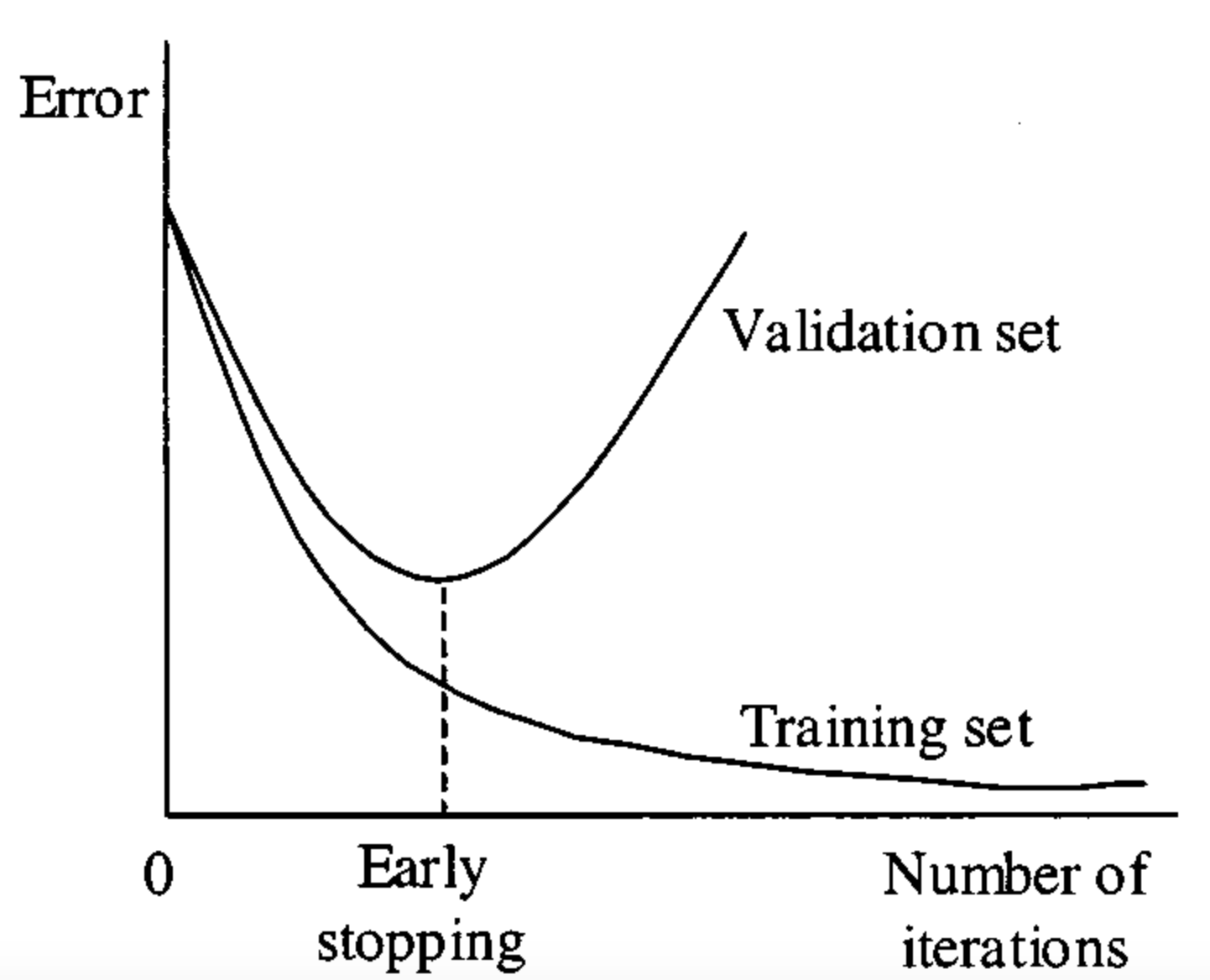

What do we mean when we say “early stopping”? Early stopping was developed as a regularization technique to prevent model overfitting. One would monitor the prediction error on both the training set and the validation set during training. As training progressed, both types of errors would reduce, but eventually, the validation error would start to increase. This is a classic instance of overfitting and one solution was early stopping — terminating training at the point when the validation error reached its minimum.

Image credit: paperswithcode

Image credit: paperswithcode

While this is a perfectly valid technique for all kinds of models, Word2Vec isn’t one of them for a couple of reasons:

- Training loss in Word2Vec doesn’t mean a whole lot. It’s buggy and misleading; even the Gensim maintainers know this! It’s been on their To-Do list of open Issues for years (and we don’t begrudge them that — it’s a small core team doing good work!).

- Even once that issue is resolved, the final training loss has little to do with how well the resulting embeddings will perform on downstream tasks. For example, let’s suppose we trained a Word2Vec model on a small dataset and noted its final training loss. We then trained a second model using the exact same data, but this time we increased the size of the embedding vectors. Model 2 now has more dimensions to “learn.” However, since our dataset was very small, this larger model would simply resort to memorization. This would yield a lower training loss, but would ultimately result in worse embeddings that aren’t able to generalize to unseen data!

The moral of the story is that early stopping for Word2Vec should not be done to prevent overfitting. The concept of overfitting is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge by considering the training loss alone. If overfitting is your concern, embeddings should be assessed against the end application, e.g., the classification, clustering, or recommendation task you ultimately want to use your embeddings for. Experimenting with various vector sizes for a fixed amount of data will do more to prevent overfitting than early stopping.

With that out of the way, let’s look at times when early stopping Word2Vec does make sense.

Do use early stopping to save compute

Instead of preventing overfitting, there are times when we simply wish to interrupt Word2Vec’s training loop before it completes the specified number of epochs in order to conserve computational resources. We thought of two situations where this could come in handy: during hyperparameter optimization, and as a way to train for a sufficiently large number of epochs without having to include epochs as a hyperparameter.

Hyperparameter tuning

Word2Vec has a host of hyperparameters, from the embedding vector size to the learning rate, to more esoteric quantities like the context window size and negative sampling exponent. The defaults stored in Gensim’s Word2Vec implementation come directly from the academic literature in which the authors empirically determined hyperparameter values that work well for most natural language tasks.

But what if you aren’t learning embeddings for word tokens? In the paper Word2Vec applied to Recommendations: Hyperparameters Matter, the authors use Word2Vec to learn embeddings for all kinds of entities: songs in a music queue, articles browsed on a news website, and products purchased on an e-commerce store. They demonstrate that tuning Word2Vec is crucial for achieving useful embeddings.

But hyperparameter optimization is expensive, especially on very large corpora. And Gensim’s implementation, while fast, is not implemented for GPUs, so you’ll want to make the most of the CPUs at your disposal. One way to do this is to identify poorly-performing hyperparameter configurations during the optimization phase and terminate them early.

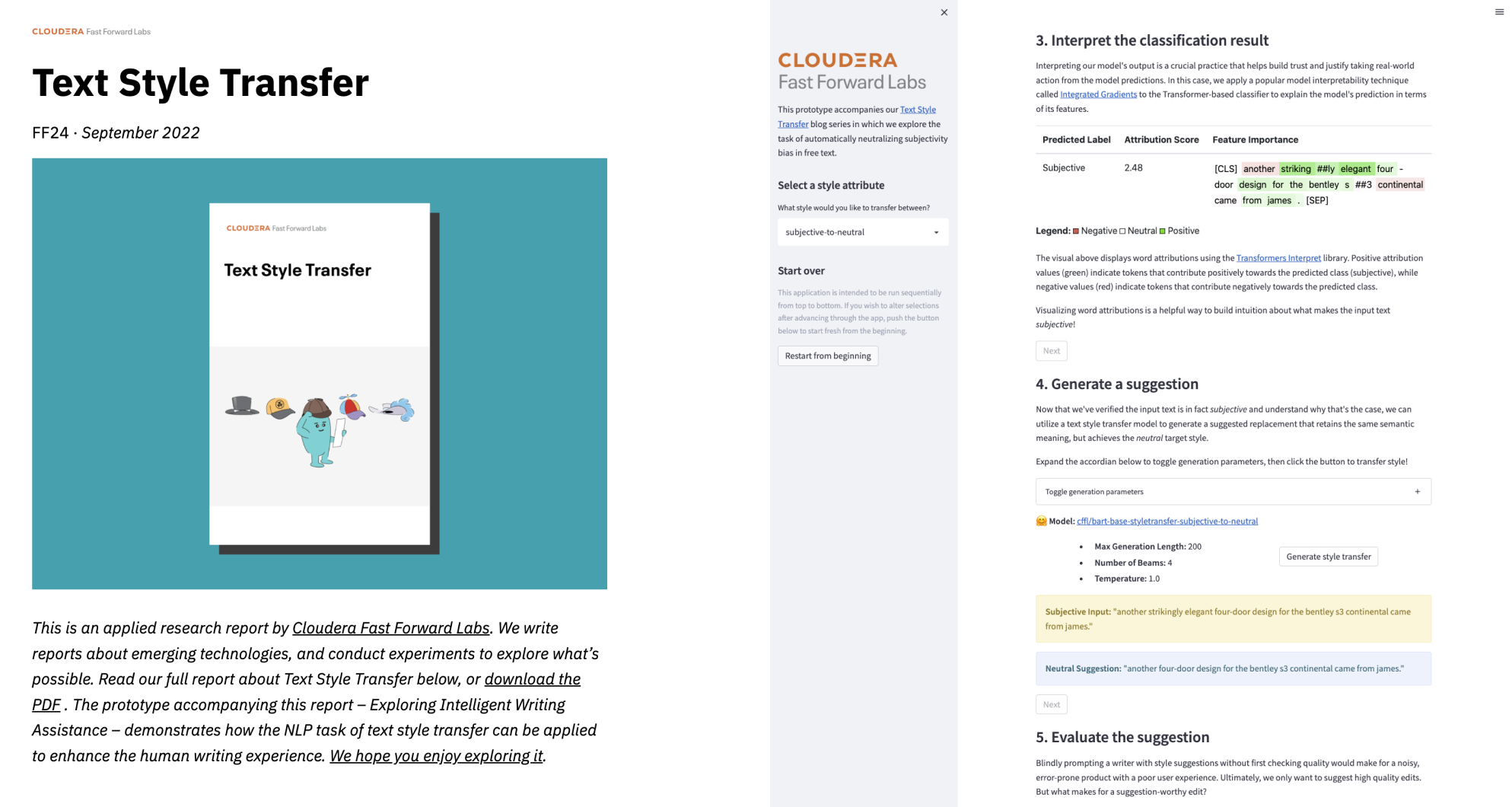

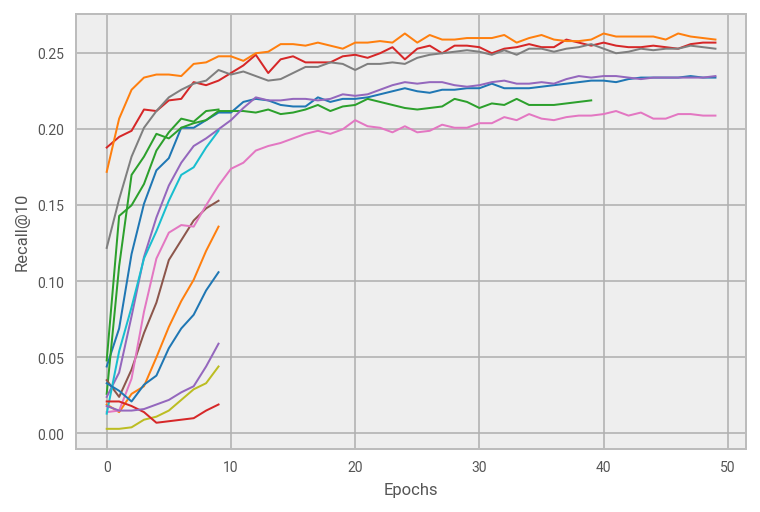

Here we show the results of early stopping during hyperparameter tuning for Word2Vec trained on product IDs for an e-commerce use case. Each colored curve represents a different hyperparameter configuration. We evaluate the embeddings we’ve learned up to that epoch on a metric appropriate for our downstream task (Recall@10 for providing recommendations). Using sophisticated scheduling algorithms provided by the Ray Tune library (more on this below), we can automatically terminate underperforming configurations in a principled fashion, thus saving loads of compute time: of the fifteen attempted configurations, only six were trained for a full fifty epochs.

Avoid tuning the number of epochs

In the figure above we saw that the top hyperparameter configurations were each trained for fifty epochs. But how do you know how many epochs to train for?

This may seem like a simple question but it quickly becomes trickier when you consider that Word2Vec was designed to train with a learning rate that decays over the course of training. This is all worked out for you behind the scenes in the implementation details, but it means that you absolutely should not try to design your own training loop to control the number of epochs. (Related: see this StackOverflow post in which one of the Gensim maintainers illustrates why you shouldn’t do this.)

One option is to include epochs as a tunable hyperparameter during optimization, but that can quickly explode the number of configurations to validate. Thankfully, there’s another way.

We need to provide the model with a guesstimate of the number of epochs: too few and the model will underfit; too many and nothing really bad will happen — the model’s embeddings will converge and additional training won’t have much effect. Therefore, it’s safer to err on the side of more epochs. However, there are computational costs associated with this choice. Training for many more epochs than is necessary to achieve good results is wasteful and time-consuming. It would be better to train for exactly what you need. But since you don’t know that a priori, this is a time when you might enter in a very large number of epochs and then consider early stopping.

How do we know when to stop? Our goal is to achieve quality embeddings so we can monitor those embeddings on a downstream task and stop training once those metrics plateau. Refer again to the figure above. Only seven hyperparameter configurations moved past the first round of early stopping, and most of those had Recall@10 scores that plateaued after about thirty epochs of training. There may still be some additional upward trend in the blue, purple, and pink runs, but the orange, red and grey look quite flat. It’s likely that many of these runs have trained such that the embeddings are about as good as they’re going to get. We thus could have saved additional compute time by terminating training runs in which our desired metric has plateaued.

Of course, the drawback with this approach is that it only works if you have a downstream task in mind and appropriate metrics that can evaluate embeddings against that task.

Time for code!

As of Gensim 4.0, *2Vec models do not have an early stopping feature. While there has been discussion of including such functionality in the future (see this Issue), it’s not currently on the road map. We’ll need help from another library: Ray Tune. Ray Tune is a Python library for experiment execution and hyperparameter tuning at scale. It also supports state-of-the-art scheduling algorithms for efficiently handling hyperparameter optimization. (Interested in HPO? Check out our deep dive on the subject here!)

Callbacks

In order for Ray Tune to monitor our Word2Vec model and perform early stopping for us, we need to provide it with information on how the model is performing during training. For this, we’ll take advantage of Gensim callbacks. The examples on the Gensim documentation depict how to report information about the model or the training itself (the current epoch, for example). But we need something more sophisticated: we need to monitor how the embeddings we’ve learned so far are performing on a downstream task. This means we need to access the KeyedVectors method of the model during training. This is actually a bit tricky because we need to simulate training completion during which the embeddings are normalized for downstream use. To do this, we make a deepcopy of the model (so that the original model can continue training in the next epoch).

import copy

from gensim.models.callbacks import CallbackAny2Vec

class RecallAtKLogger(CallbackAny2Vec):

'''Report Recall@K metric at end of each epoch

Computes and reports Recall@K on a validation set with

a given value of k (number of recommendations to generate).

'''

def __init__(self, validation, k=10, ray=False):

self.epoch = 0

self.validation = validation

self.k = k

self.ray = ray

def on_epoch_end(self, model):

# make deepcopy of the model and emulate training completion

mod = copy.deepcopy(model)

mod._clear_post_train()

# compute the metric we care about on a recommendation task

# with the validation set using the model's embedding vectors

score = 0

for query_item, ground_truth in self.validation:

try:

# get the k most similar items to the query item

neighbors = mod.wv.similar_by_vector(query_item, topn=self.k)

except KeyError:

pass

else:

recommendations = [item for item, distance in neighbors]

if ground_truth in recommendations:

score += 1

score /= len(self.validation)

if self.ray:

tune.report(recall_at_k = score)

else:

print(f"Epoch {self.epoch} -- Recall@{self.k}: {score}")

self.epoch += 1

Early Stopping with Ray Tune

Once we have our Gensim Callback, early stopping with Ray Tune is easy!

from gensim.models.word2vec import Word2Vec

from ray import tune

from ray.tune.schedulers import ASHAScheduler

from ray.tune.stopper import TrialPlateauStopper

# this helper function is what Tune uses to optimize hyperparameters

def tune_w2v(hyperparameters:dict):

""" Hyperparameter optimization wrapper for Ray Tune"""

# instantiate our callback logger

ratk_logger = RecallAtKLogger(valid, k=10, ray_tune=True)

# instantiate our model and pass our callback and hyperparameters

model = Word2Vec(sentences=train, callbacks=[ratk_logger], **hyperparameters)

# define the search space of hyperparameters (we're performing a random search)

# we conclude the search space with some fixed hyperparameters that we want

# passed to the model every time, including the number of epochs ("iter")

search_space = {

"size": tune.randint(10, 100),

"window": tune.randint(3, 25),

"ns_exponent": tune.quniform(-1.0, 1.0, .2),

"alpha": tune.loguniform(1e-4, 1e-2),

"negative": tune.randint(1, 25),

"iter": 50, # number of epochs

"min_count": 1, # number of instances a token appears before word2vec creates an embedding vector for it

"workers": 6, # number of CPU workers

"sg": 1, # trains the skip-gram version of word2vec

}

# ASHA terminates under-performing hyperparameter configurations in a principled way

asha_scheduler = ASHAScheduler(max_t=100, grace_period=10)

# terminates training sessions in which the monitored metric has plateaued

stopping_criterion = TrialPlateauStopper(metric='recall_at_k', std=0.002)

# Let Ray Tune optimize!

analysis = tune.run(

tune_w2v,

metric="recall_at_k",

mode="max",

scheduler=asha_scheduler,

stop=stopping_criterion,

verbose=1,

num_samples=15, # number of trials to attempt

config=search_space

)

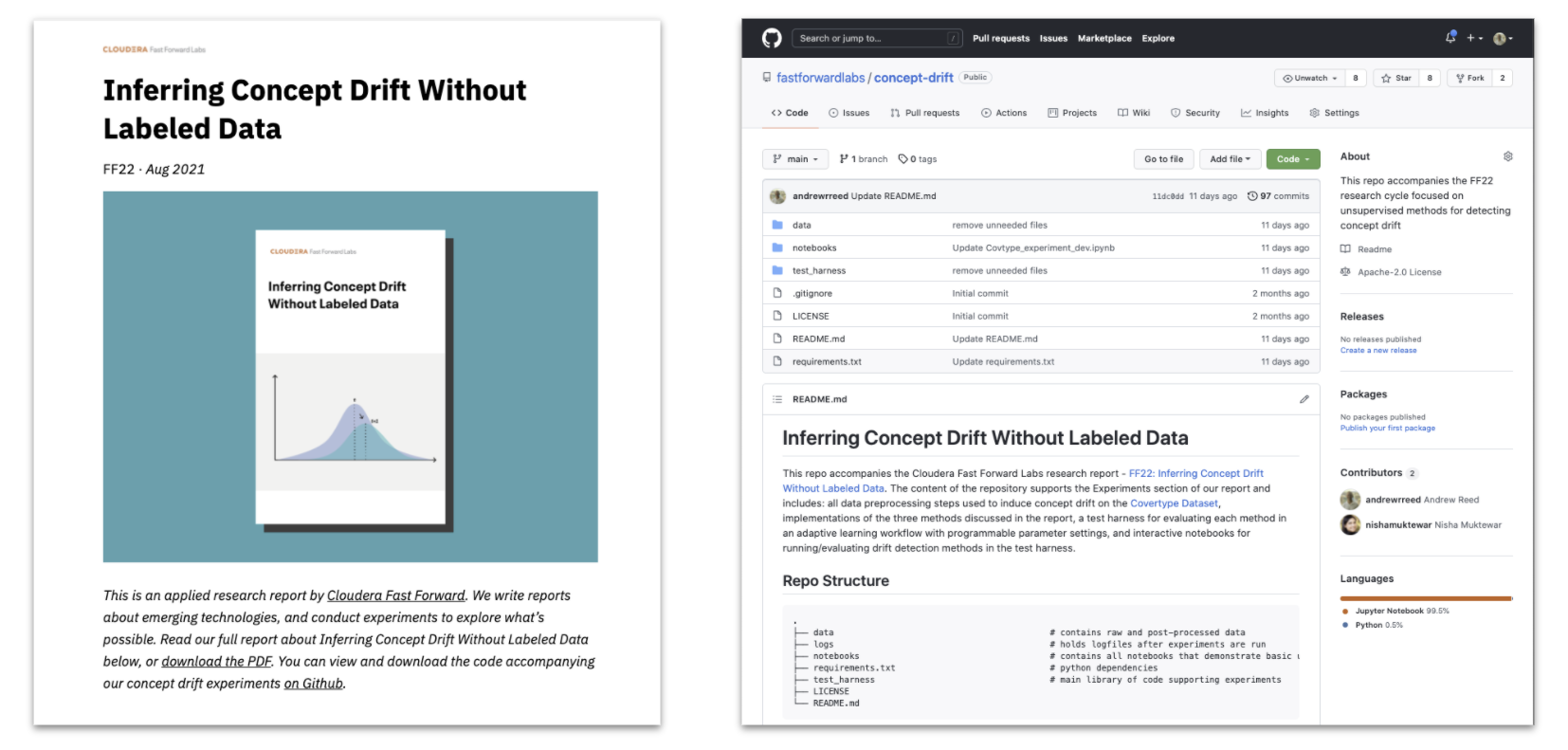

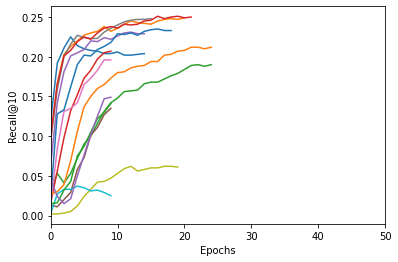

Look at the results now! We’ve plotted them on the same scale as the figure above and the difference is striking. Not a single training run ran for the full 50 epochs! Some were stopped by the ASHA Scheduler due to suboptimal hyperparameter values; others were stopped due to a plateau in the downstream metric we were monitoring. And if we examine the best performing model in both experiments, each yields embeddings with roughly the same amount of predictive performance for our downstream recommendation task, indicating that we didn’t have to sacrifice quality for speed-up.

There are, of course, many caveats, mostly due to randomness in these experiments. The hyperparameter optimization we perform uses a random search so the resulting models are certainly not identical. Even if we fixed the hyperparameter values (say, via a grid search), there would still be minor differences since Word2Vec is randomly initialized before training.

These methods also rely on a crucial requirement: that you have a downstream task in mind and have chosen a metric suitable for measuring its success. We demonstrated that through a simple recommendations application: we learned product embeddings and then evaluated how successful they were against a set of ground truth user data.

Conclusion

We did it! We performed two kinds of early stopping on Gensim’s Word2Vec in a principled way using the algorithms provided by the Ray Tune hyperparameter optimization library. What embeddings are you going to train next?