Sep 22, 2021 · post

Automatic Summarization from TextRank to Transformers

Automatic summarization is a task in which a machine distills a large amount of data into a subset (the summary) that retains the most relevant and important information from the whole. While traditionally applied to text, automatic summarization can include other formats such as images or audio. In this article we’ll cover the main approaches to automatic text summarization, talk about what makes for a good summary, and introduce Summarize. – a summarization prototype we built that showcases several automatic summarization techniques.

Automatic text summarization allows users to glean the most relevant information in large volumes of text, a task that has become increasingly relevant as more and more text data is mined for insights. This application thus has broad appeal for many business use cases like distilling financial statements into manageable summaries, paraphrasing legal documents, or collating major themes from a collection of corporate documents. While some of these use cases are more advanced, in this post we’ll talk about the foundations: techniques for summarizing individual documents into short summaries.

Approaches

There are two main approaches to automatic summarization: abstractive and extractive.

Extractive

In extractive summarization, the goal is to identify and extract subsets of the original text that best represent the most relevant information. These extracted subsets could be keywords or phrases, but are often whole sentences. Models that perform extractive summarization have been around for decades, including supervised and unsupervised approaches (more on this below). These models have one thing in common: they each seek to essentially rank every subpassage (e.g., each sentence) in the document according to some metric of importance. Summaries are then constructed by selecting the most important subpassages.

Extractive summaries are attractive because they pull text verbatim from the document, allowing the summary to faithfully reproduce the wording of the original content. On the other hand, summaries constructed this way can suffer from a lack of context: sentences can be extracted from all over the document and, when strung together, they often lack important contextual references. For example, a sentence in the summary might refer to “she” or “they” but may fail to include the sentence that clarifies the reference. Thus extractive summaries can sometimes be difficult to read or follow.

Abstractive

The goal of this approach is to paraphrase the original text, rather than extracting representative segments. This is more akin to how a human would summarize a document or article. Models that perform this type of summarization well have only recently emerged. These are, of course, deep learning models, specifically the Transformer architecture (we’ll cover more below). In this approach, the model ingests the document and then generates a summary word by word. Often this summary contains specific phrases from the document verbatim, but other times the verbiage is paraphrased.

While this style of summarization suffers less from contextual inconsistencies, automatic text generation is far more susceptible to misrepresentation errors. This happens when the model’s paraphrase twists the context of the original text. We’ll touch on this more in a later section.

Models for automatic summarization

Let’s learn more about some of the models that can perform automatic text summarization. In this section we cover the models that we deployed in our prototype Summarize. These models range from classic unsupervised approaches, to deep learning-based Transformer models, and even a hybrid approach.

TextRank

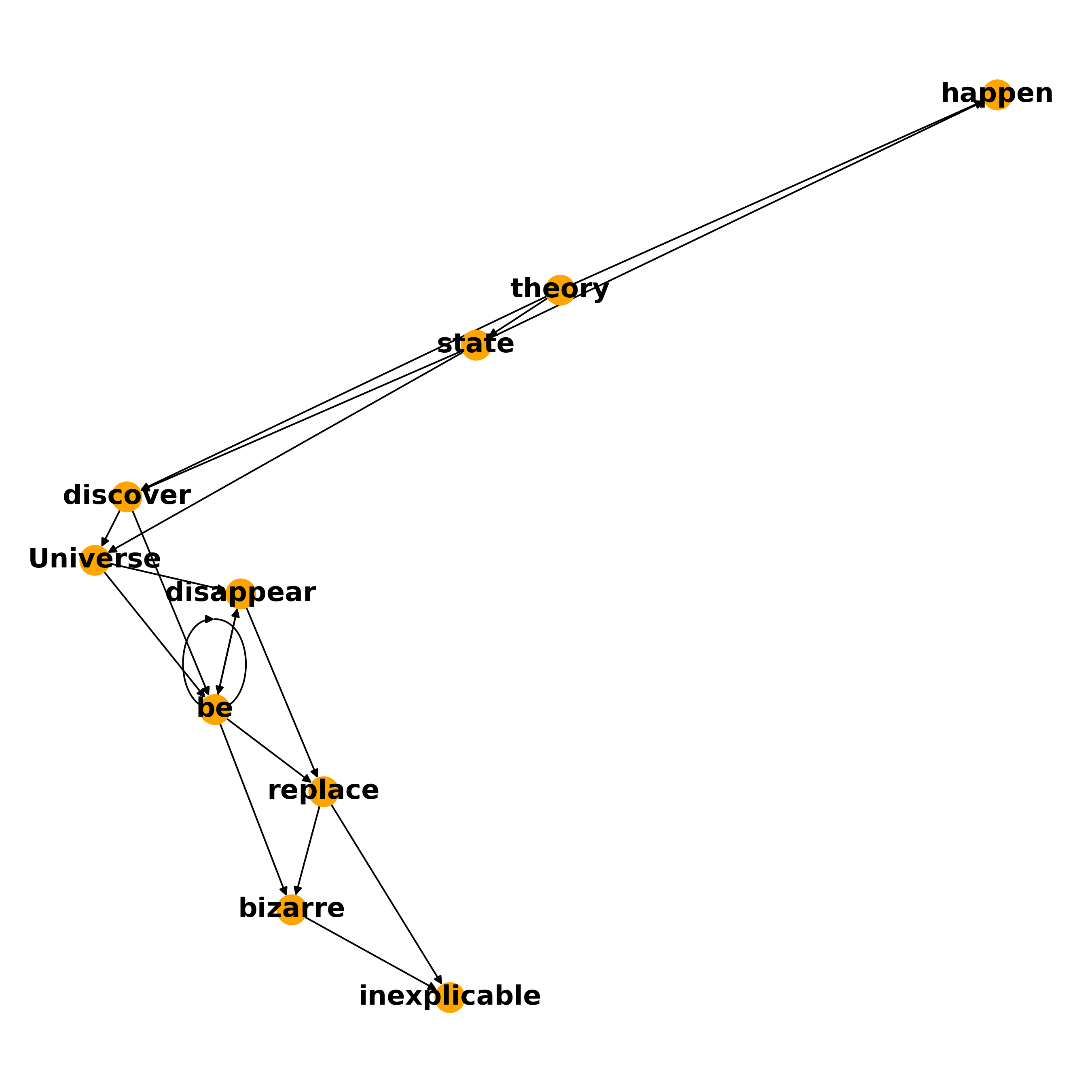

TextRank is a classic graph-based ranking algorithm that assigns text to each node of a graph. The edges are assigned a value that represents a notion of similarity between two vertices. For example, in the classic version of this model, each vertex is assigned a word from the document, and the edges are the co-occurrence of those words within a given context window size passed over the document. We can visualize this graph by considering the following passage (from the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy):

There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.

After discarding stop and other filler words, and lemmatizing (reducing words to their root), a TextRank graph with a context window size of 2 would look like this:

Fig. Example of a TextRank graph. Each node is a word and has a connection to another word if that word is within a context window of 2 in the original text.

Fig. Example of a TextRank graph. Each node is a word and has a connection to another word if that word is within a context window of 2 in the original text.

Once the graph is constructed, the next step is to compute the “importance” of each vertex given global information about the entire graph. The basic idea is that of voting: when two vertices are linked, they “vote” for each other, and votes from important vertices (those with many votes) count for even more. These importance scores are computed by running the PageRank algorithm (of search engine fame) on the text graph. Vertices with the highest scores are used to determine the most important words and phrases, and a summary is constructed by extracting sentences containing these top words and phrases.

This model is attractive due to its simplicity, and because it’s an unsupervised approach – it doesn’t require labeled training data. It can also be used on documents of any length, something that our next family of models struggles with.

Transformers

The Transformer architecture has revolutionized natural language processing, producing dramatic results in myriad tasks from text classification, to question answering, and, of course, summarization. Transformer architecture is composed of one or two stacks: all Transformers have an encoder stack, which processes input text into numerical representations. Some Transformers also have a decoder stack, which generates text word by word. All Transformers are first trained on a massive amount of text in an unsupervised fashion to become Language Models (LMs), models that have learned the syntactic and semantic relationships of a language.

From here, applications diverge. Used as-is, LMs are adept at computing numerical contextual text representations (“embeddings”) that can be used as features in a host of downstream tasks. LMs can also be fitted with classification or regression components and fine-tuned (supervised training on a labeled dataset) to perform a specific task, like question answering or sentiment analysis. LMs that have the decoder stack can perform language generation tasks such as translation or summarization.

In the Summarize. prototype, we used Transformers in all three ways! Here, we provide a bit more context on each method.

Transformers for abstractive summarization

Transformers with both the encoder and decoder architectures can ingest a document through the encoder and generate a summary word by word via the decoder. While these models currently represent the state-of-the-art in text summarization, they have some drawbacks. Of primary concern is the factual inconsistency problem that we mentioned earlier. These Transformer models occasionally generate a summary that no longer faithfully reproduces the intent of the original document.

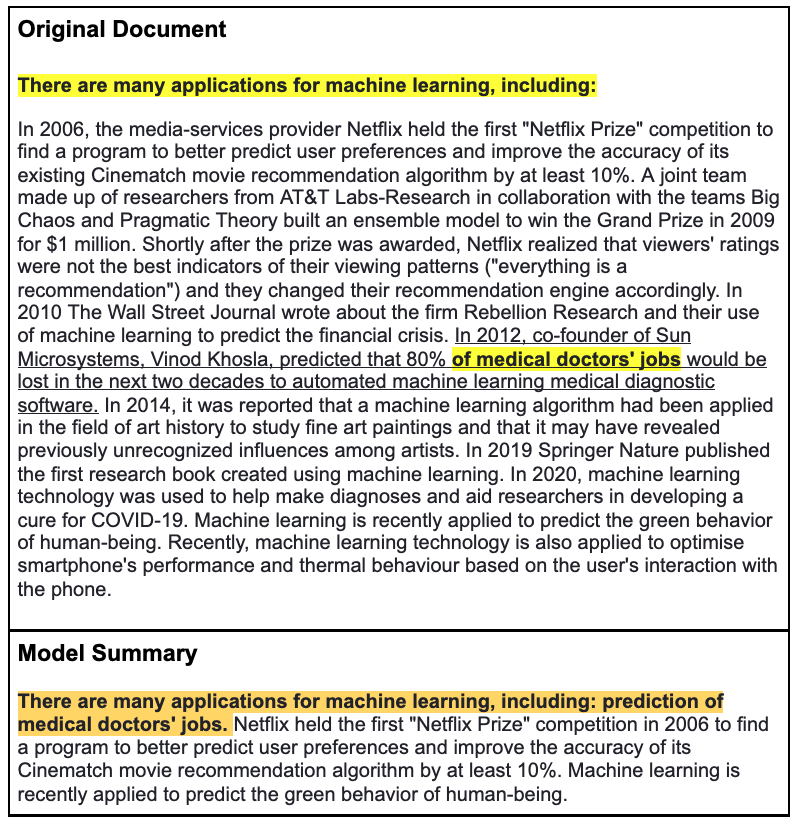

Consider the example below. In the top half we present an excerpt from the Wikipedia article on Machine learning. (The original excerpt included a bulleted list that was excluded by our text processing pipeline.) We’ve highlighted in yellow segments of the document that were included in the model’s summary. In the bottom half is the model’s summary, where we’ve highlighted the first sentence in orange.

The first sentence of the model’s summary is rather surprising: An application of machine learning is the prediction of medical doctors’ jobs? Not only is this confusing, it is not a faithful representation of the original document. While those phrases are found in the original (highlighted in yellow), the model has made an incorrect paraphrase that twisted the meaning of the original text. If we read the original document, we see that machine learning models are not predicting medical doctors’ jobs – instead, the co-founder of Sun Microsystems predicted that many medical doctors’ jobs will be replaced with machine learning models!

While state-of-the-art Transformer models have minimized the frequency of these errors, they remain an unsolved problem and are difficult to detect. These models are also saddled with additional drawbacks including increased computational complexity, and limitations on the amount of text that can be processed at a given time. However, the utility of readable, human-sounding summaries could outweigh these drawbacks for some use cases.

Transformers for extractive summarization.

But we can also train Transformers to perform extractive summarization by framing the task as a classification problem. To do this we outfit a Transformer with a classification module and fine-tune it on a labeled dataset. In this case, the dataset should consist of documents in which each sentence of every document is labeled with a 1 (include in the summary) or 0 (do not include in summary). We trained a model in just this way and wrote a much more detailed blog post on how we did it in Extractive Summarization with SentenceBERT. At inference time, the model computes a score for each sentence in the document. Those with the highest scores are extracted as the document summary.

Hybrid

The hybrid approach we explored combines elements from both TextRank and Transformers. In this approach we still use TextRank to build a graph, but each vertex represents a sentence from the document, rather than a single word. A Transformer model (SentenceBERT, specifically) is used to compute embeddings for each sentence. Rather than co-occurrence (which doesn’t have much meaning for sentences), the edges of the graph are the cosine similarity between each pair of sentence representations. As before, the PageRank algorithm computes the final importance scores for each sentence in the document, and sentences with the highest scores are selected as the document summary.

What makes for a good summary?

Let’s take stock. We have a general sense for the various types of summarization techniques and we’ve covered a few models that can perform the task. But how good are the summaries?

That’s a tricky question for many reasons. Summarization is hard in large part because “good” summaries are subjective. Furthermore, there is no single “correct” answer – any document will have several equally suitable summaries. Another challenge is that summarization is an inherently lossy endeavor. There is no way to encapsulate every pertinent piece of information, except to not summarize at all! This means that any summary – abstractive or extractive, classically obtained or state-of-the-art generated – will yield a summary that fails to include some piece of information that may have been relevant to some users.

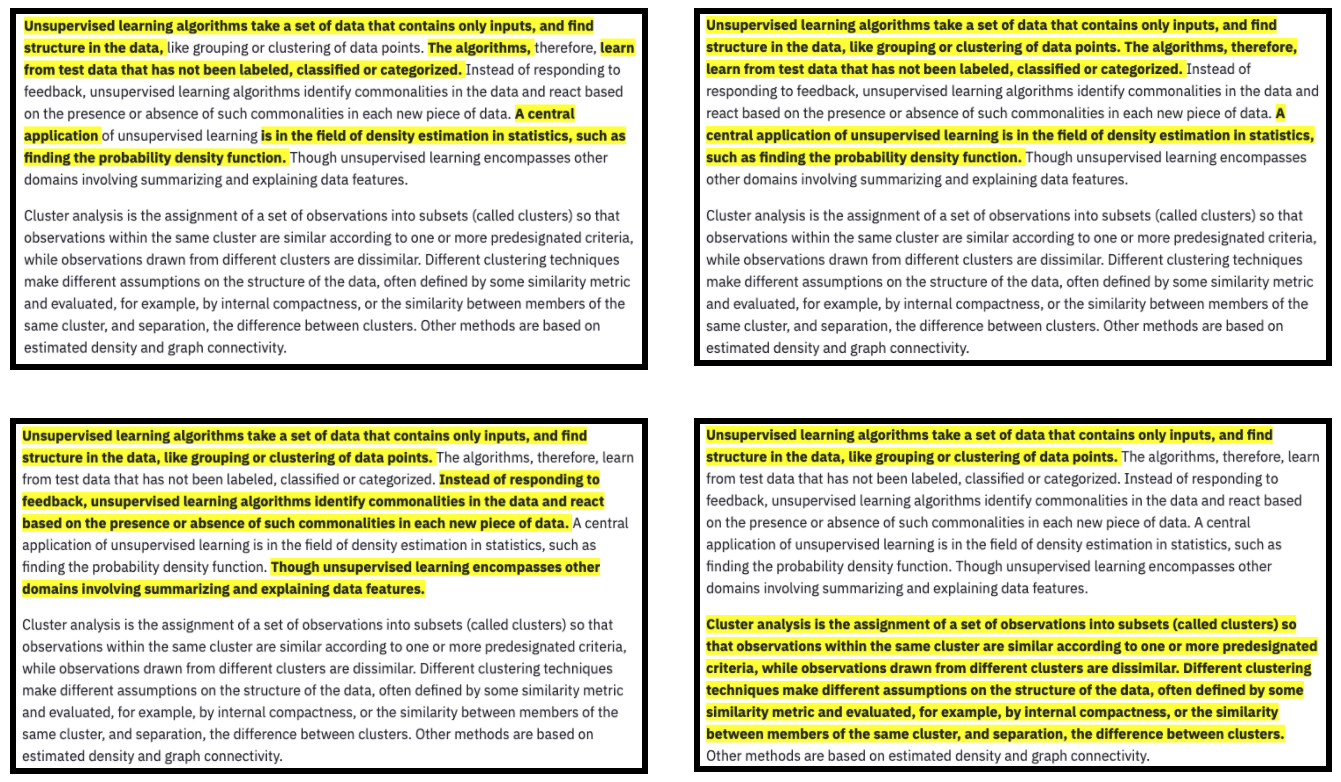

Below is an excerpt of a Wikipedia article about machine learning. We applied four different summarization models to the text and highlighted the resulting summary from each model. As you can see, each summary identifies starkly different information from the others. None of them would be inherently wrong and, ultimately, it’s up to the user to determine the utility of each model.

Fig. Four models yield four very different summaries (highlighted). Ultimately, humans must determine which yields the most utility.

Fig. Four models yield four very different summaries (highlighted). Ultimately, humans must determine which yields the most utility.

Of course, when building a summarization model for a specific use case we need a way to systematically compare models in order to identify which has the greatest utility for our situation. And that means gold standard summarization datasets.

Evaluating summarization models

Most summarization datasets facilitate abstractive summarization, rather than extractive. For example, the canonical CNN/Daily Mail dataset includes nearly three hundred thousand news articles, each paired with a summary written by a human journalist. While providing a powerful training resource, this dataset is nevertheless imperfect because each news article has only a single summary, and was written by a journalist with a specific writing style and preconceived notion of what constitutes the most important aspects of the full-length article.

An extractive summarization dataset, on the other hand, would have documents labeled with which text segments should be included in the summary and which should not. These are harder to come by, and often abstractive datasets are repurposed for extractive summarization, which adds another caveat to the evaluation process. (You can read more about how we performed this repurposing ourselves in our technical blog post.)

Keeping these caveats in mind, we can assess a summarization model against one of these datasets by comparing the model’s summary to the gold standard summary of a test set via a ROUGE score. Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation may not sound like an intuitive name but the important part is the first word: recall. While there are half a dozen flavors of ROUGE score, at their core each is a measure of recall between the model’s summary and the gold standard summary. The most common versions compute recall on unigrams (splitting the summaries into individual words), or bigrams (splitting the summaries into pairs of words). These versions don’t consider the sentence structure or the order of words in the summary. To that end, the ROUGE-L score considers the longest common subsequence between the summaries.

While the ROUGE scoring framework provides a standardized way to compare models, ROUGE scores alone cannot evaluate a summary for readability, writing style, consistency, or factual correctness. As always, additional human evaluation of the summaries in these categories is recommended.

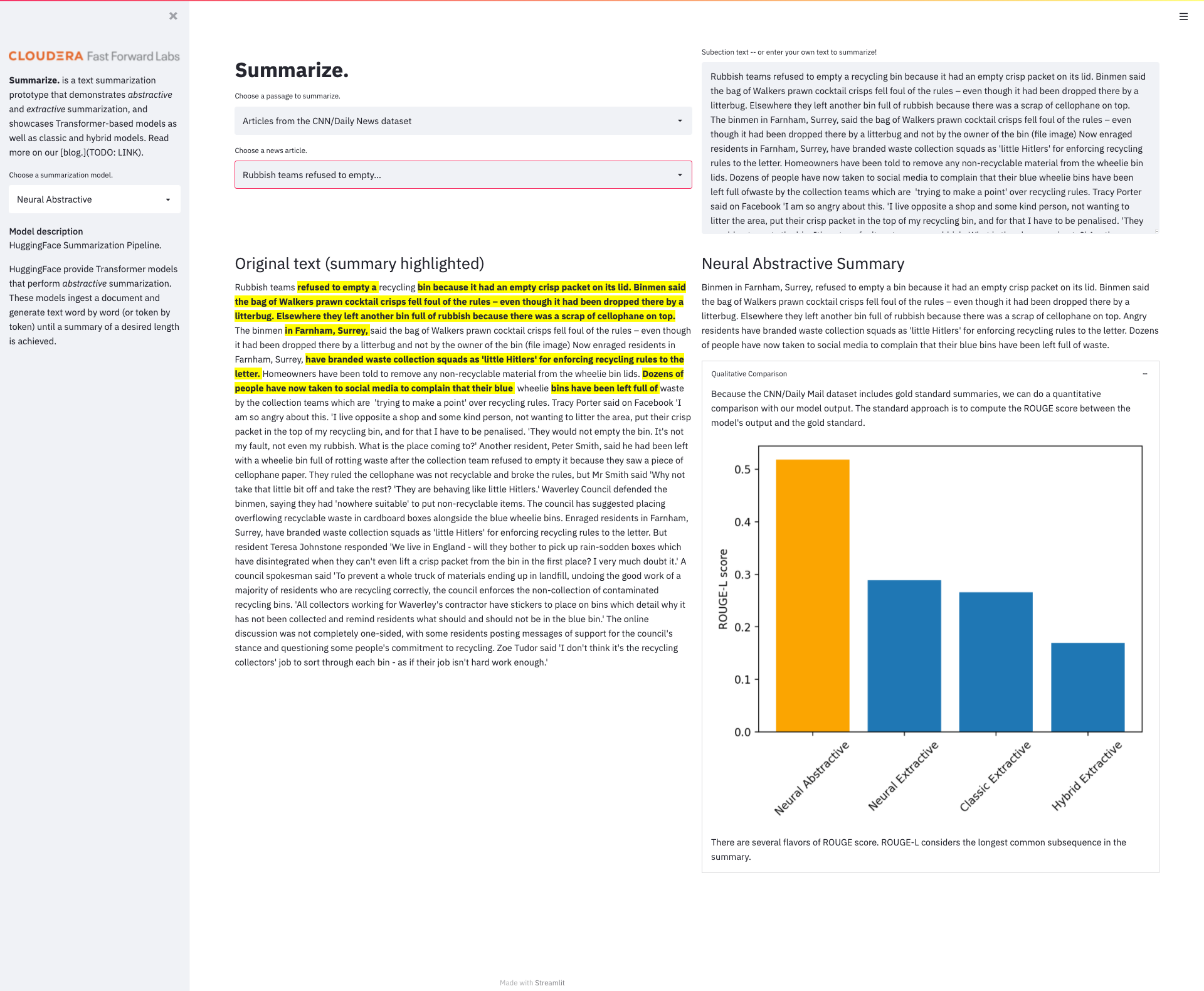

New Applied Machine Learning Prototype

We crammed everything we talked about in this article into a new applied machine learning prototype called Summarize. Summarize. allows the user to interact with the four different summarization models discussed above. We include several example articles from Wikipedia and the CNN/Daily Mail dataset to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each model. We’ve also computed the ROUGE-L scores for each model against the gold standard summary provided by the CNN/Daily Mail dataset. Additionally, you can enter your own text for summarization!

Summarize. is a simple Streamlit application and you can try it out for yourself by heading to this repo. It can be run locally or spun up as a CML Application via the CML AMP Catalog. Installation and other details can be found in the repo.

Happy summarizing!