Dec 14, 2021 · post

An Introduction to Video Understanding: Capabilities and Applications

Video footage constitutes a significant portion of all data in the world. The 30 thousand hours of video uploaded to Youtube every hour is a part of that data; another portion is produced by 770 million surveillance cameras globally. In addition to being plentiful, video data has tremendous capacity to store useful information. Its vastness, richness, and applicability make the understanding of video a key activity within the field of computer vision.

“Video understanding” is an umbrella term for a wide range of technologies that automatically extract information from video. This blog post introduces video understanding by presenting some of its prominent capabilities and applications. “Capabilities” describe ways in which video understanding is made concrete by machine learning practitioners. “Applications” are the specific ways in which these technologies are used in the real world.

Concurrent with the publication of this blog post, Cloudera Fast Forward Labs is also releasing an applied prototype focused on video classification, which is one of the video understanding capabilities described herein.

What Is Video Understanding?

To better comprehend video understanding, it is useful to explore some of the capabilities (or tasks) associated with video understanding. Here, we describe five of them:

- Video Classification

- Action Detection

- Dense Captioning

- Multiview and Multimodal Activity Recognition

- Action Forecasting

Readers who are familiar with computer vision as applied to still images might wonder about the difference between image and video processing. Can’t we just apply still image algorithms to each frame of a video sequence, and extract meaning in that way?

While it is indeed possible to apply image methods to each frame in a video (and some approaches do), considering temporal dependencies results in tremendous gain in regard to capabilities. For instance, still image algorithms can predict whether or not there is a door in an image, but they’ll be poor at predicting whether the door is opening or closing. This gain in predictive capabilities comes at the cost of algorithmic complexity and computational requirements. Together, those capabilities and challenges make video understanding a fascinating area within the field of computer vision.

Video Classification

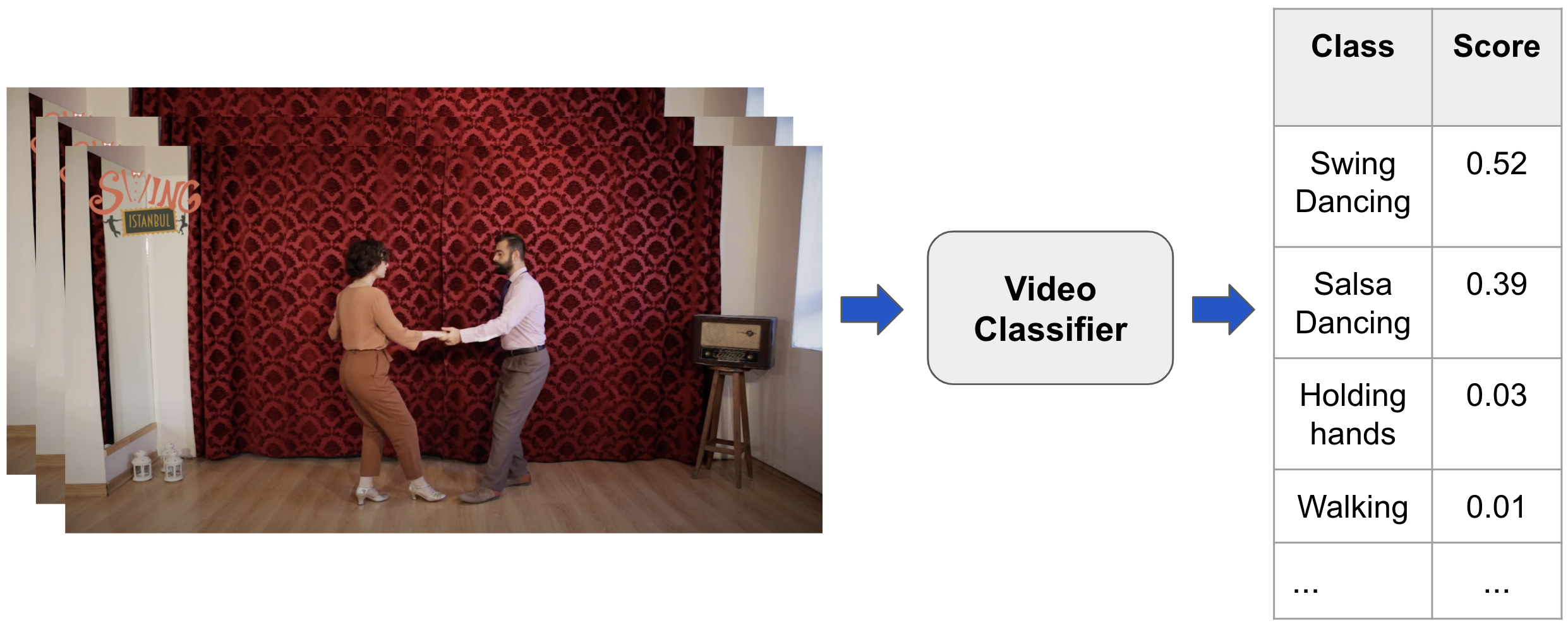

Video classification is one of the most basic video understanding tasks, wherein the goal is to identify an action in a video. A model achieves this by assigning to a video a set of scores, each corresponding to an action class. The score indicates how likely it is that the action is being performed at any point during the video.

Figure 1 illustrates this task. On the left is a stack of images representing the video that is being classified. This video is fed into the Video Classifier, which outputs a table (shown on the right) with action classes and a score for each class. In this example, the classes are “swing dancing,” with a score of 0.52, “salsa dancing,” with a score of 0.39, plus a few other classes with lower scores. Visual inspection of the image (by a human) indicates that “swing dancing” makes sense as the proper classification.

Figure 1. Illustration of video classification. The image on the left represents the video being classified, which is taken from a YouTube video which forms part of the Kinetics 400 dataset. On the right are the predicted classes and their probabilities.

Figure 1. Illustration of video classification. The image on the left represents the video being classified, which is taken from a YouTube video which forms part of the Kinetics 400 dataset. On the right are the predicted classes and their probabilities.

Note that the set of scores is given for the video as a whole, rather than on the basis of individual frames (which is done for action detection, explained in the next section). In this basic form, video classification is intended to be used with video that has been trimmed, in advance, in such a way that it contains only one predominant action. This limits the direct applicability of the task. In practice, modifications need to be made for the task to be useful to solve real-world problems.

Action Detection

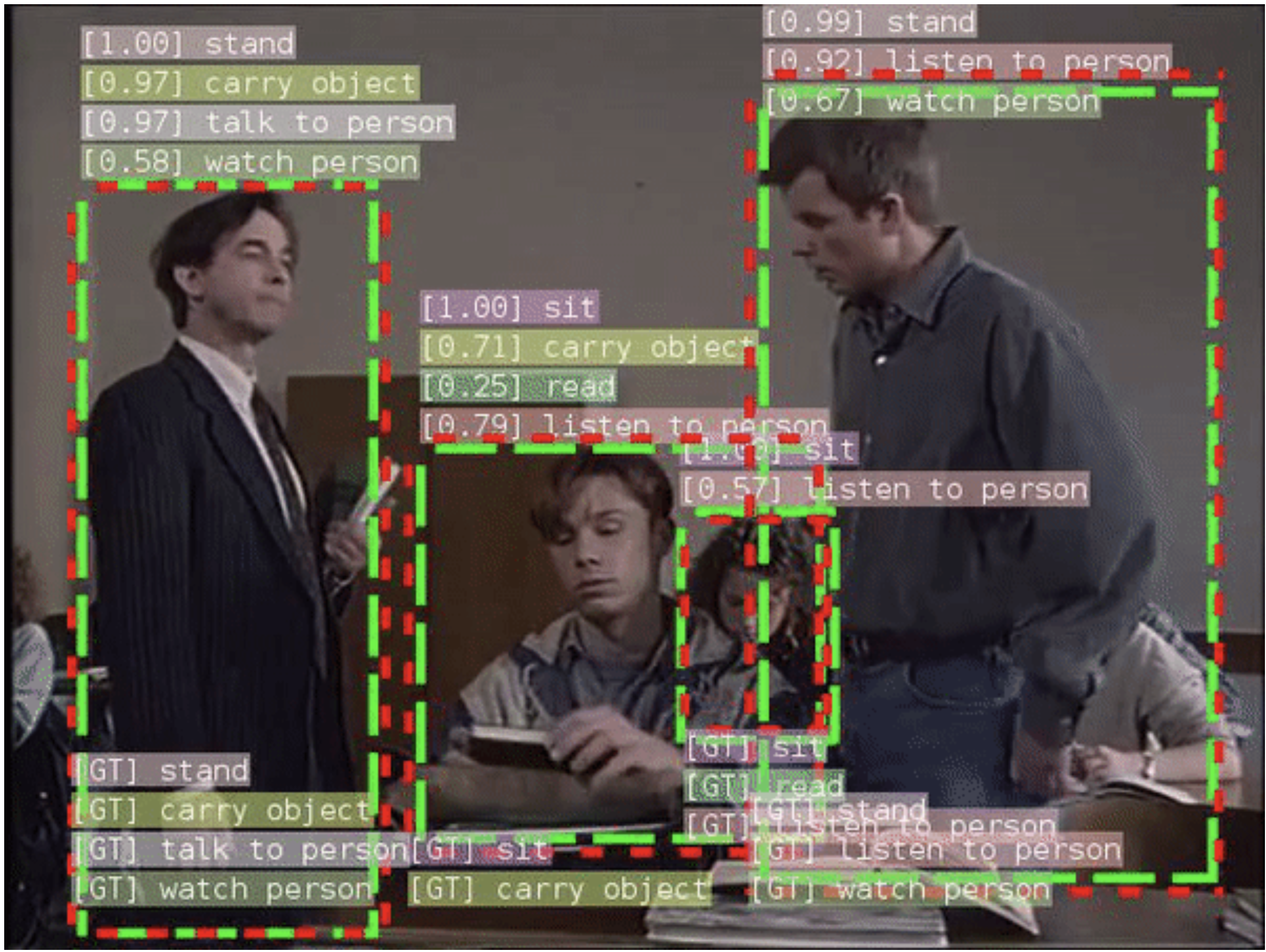

Action detection is a task with significantly higher complexity than video classification. Conceptually, it contains the sub-tasks of object detection (where the agents are located), object tracking (where the agents are moving to), and video classification (what actions the agents are performing), all in one. In practice, however, most techniques employed to perform action detection are not simply a combination of algorithms that perform these sub-tasks, but instead consist of dedicated methodologies. A detailed explanation of those methods is beyond the scope of this blog post; here we focus only on explaining the task itself.

Models for action detection take as input a video, and produce as output the following information on a per frame basis:

- Spatial location of agents, typically specified by bounding boxes, and

- For each of the detected agents, the probability that the agent is performing a particular action, among a set of predefined actions.

Figure 2 illustrates action detection. It contains one frame from the video that is fed to the detection model. Superimposed on the frame are the bounding boxes and the labels that are produced by the model. The boxes are used to specify the location of the agents in space: red boxes represent the location of the agents as predicted by the model; green boxes represent the agents’ “ground truth” locations as determined by a human being (noted in the figure as [GT]), and are shown to demonstrate the accuracy of the model. The image is taken from Facebook’s SlowFast repository, which implements several state-of-the-art video classification and action detection algorithms.

Figure 2. Illustration of video action detection. The image was extracted from a video that is fed into an action detection model. Superposed on the image is an illustration of the output of the model, namely a set of bounding boxes (indicating the location of agents) and sets of labels (indicating the actions that the agent is executing).

Figure 2. Illustration of video action detection. The image was extracted from a video that is fed into an action detection model. Superposed on the image is an illustration of the output of the model, namely a set of bounding boxes (indicating the location of agents) and sets of labels (indicating the actions that the agent is executing).

In addition to the location of the agents, a set of scores is produced: one for each action in a predefined set of possible actions. Each of the scores indicates the probabilities that the agent is executing the action.

In the figure, the predicted scores are shown at the tops of the bounding boxes, while the ground truth labels are at the bottom. The predictions are that the person on the left has a probability equal to 1.00 of being standing, 0.97 of carrying an object, 0.97 of talking to a person, and 0.58 of watching a person. The ground truth labels indicate that those predictions are correct, as judged by a human being. Analogous labels and bounding boxes are predicted for other persons in the image.

In addition to locating multiple agents in space, each of which have multiple action labels, the algorithm also detects when those actions are happening. This temporal aspect of the detection is done by assigning action labels on a per frame basis. This means that action detection has finer temporal and spatial granularities than video classification (in which only one label is given to a full video clip, without specifying when and where the action is performed, or by whom).

Dense Captioning

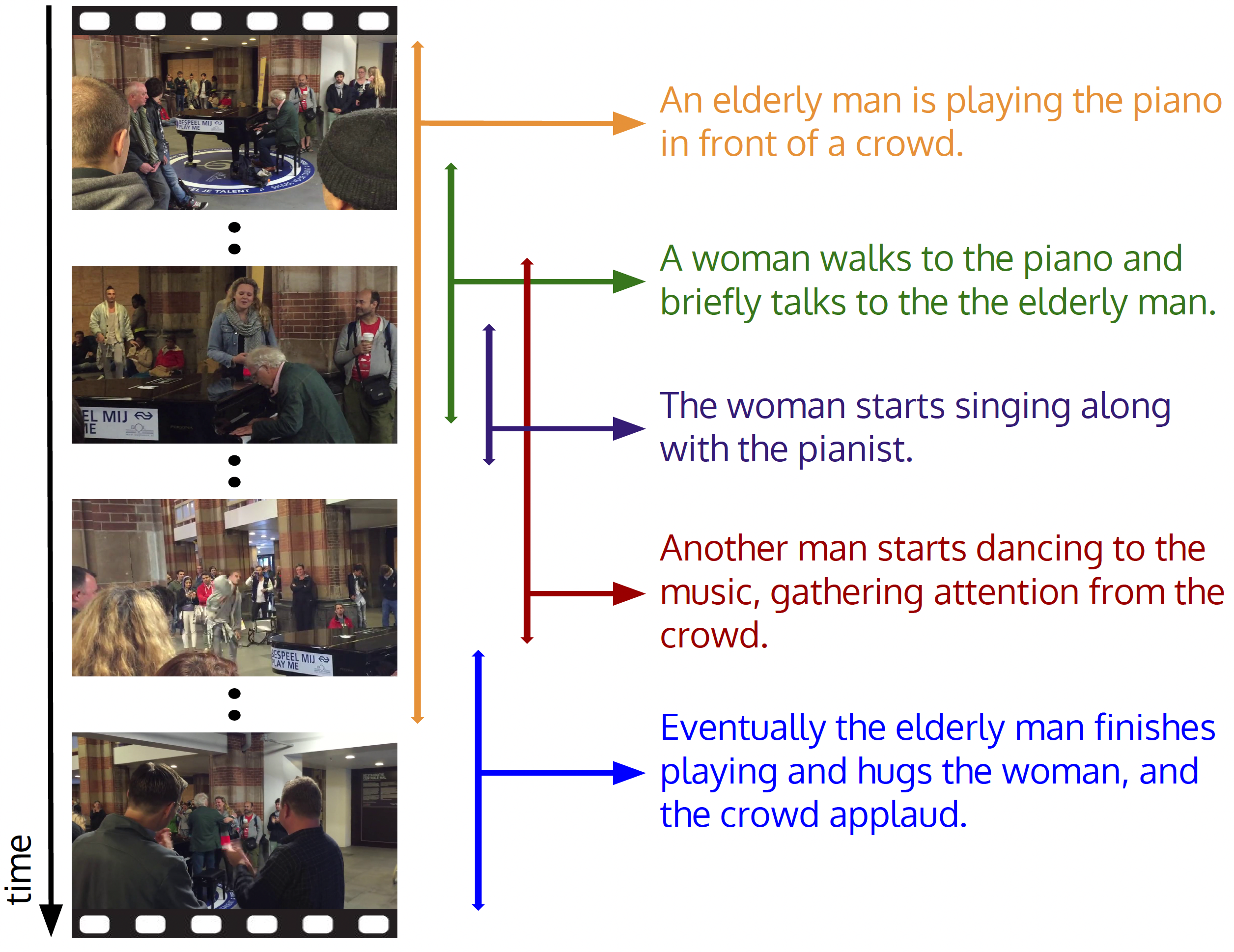

The two tasks described above — video classification and action detection — produce scores for predefined categories of actions: video classification produces one set of scores for a whole video clip, and action detection produces a set of scores for each detected agent on a per frame basis. Dense captioning goes beyond categories and assigns natural language descriptions to subsets of frames in videos.

Figure 3 illustrates the task of dense captioning. The images on the left are frames taken from a video that is fed into the algorithm. On the right are the captions for subsets of frames produced by the algorithm. Note that the captioned video segments (each of which is indicated by descriptions in varying colors) may be of different durations and may overlap with each other. For increased resolution, we recommend watching the first minute of the video from which the frames in the figure were taken.

Figure 3. Illustration of dense video captioning. Given a video, the task consists of producing a set of natural language annotations that describe what is happening at different times throughout the video. The image above is taken from [1].

Figure 3. Illustration of dense video captioning. Given a video, the task consists of producing a set of natural language annotations that describe what is happening at different times throughout the video. The image above is taken from [1].

Multiview and Multimodal Activity Recognition

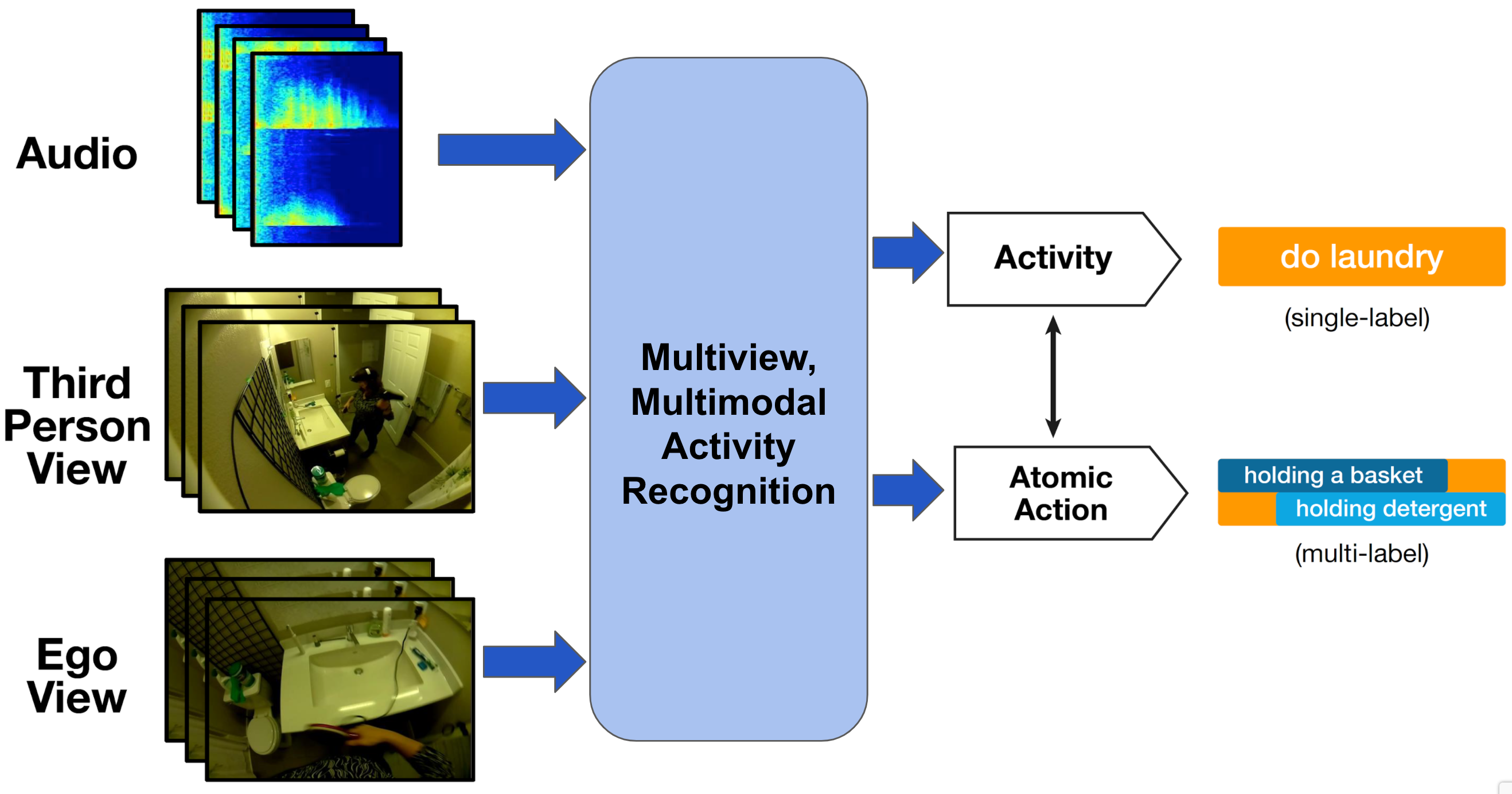

Video understanding is not restricted to using visual information from a single camera. Signals from multiple cameras can also be used, and other types of signals (like sound) can also be used in combination with visual information. Using video from multiple cameras is referred to as multiview video understanding. When the predictive models use non-visual signals, the tasks are known as multimodal.

Figure 4 illustrates a task that is simultaneously multimodal and multiview. The signals used are:

- Audio: sound captured by a microphone in a scene.

- Third-person View: video from a camera that captures the agent performing the action.

- Ego View: video captured by a camera attached to the agent performing the action, intended to capture what the agent sees.

Figure 4. Illustration of multiview, multimodal activity recognition. Three signals are fed into the predictive model, namely: audio, third-person view, and ego view. The model predicts the actions performed by the agent. The image used has been adapted from [2].

Figure 4. Illustration of multiview, multimodal activity recognition. Three signals are fed into the predictive model, namely: audio, third-person view, and ego view. The model predicts the actions performed by the agent. The image used has been adapted from [2].

In the example illustrated in this figure, the three signals are used together to make predictions about human activity. The activity consists of the high-level action “doing laundry,” as well as two low-level atomic actions, namely “holding a basket” and “holding detergent.”

Action Forecasting

Action forecasting predicts actions performed in future frames of a video, given the present and past frames. There are many variants of this task. In one of its simplest forms, a single, future, global action performed by a single agent in a video is predicted. This is analogous to video classification, but predicts probabilities of future, unobserved actions (rather than past, observed actions). A more complex variant involves determining the locations and actions of multiple agents. This is analogous to action detection, but applied to future, unobserved locations and actions (rather than present, observed locations and actions).

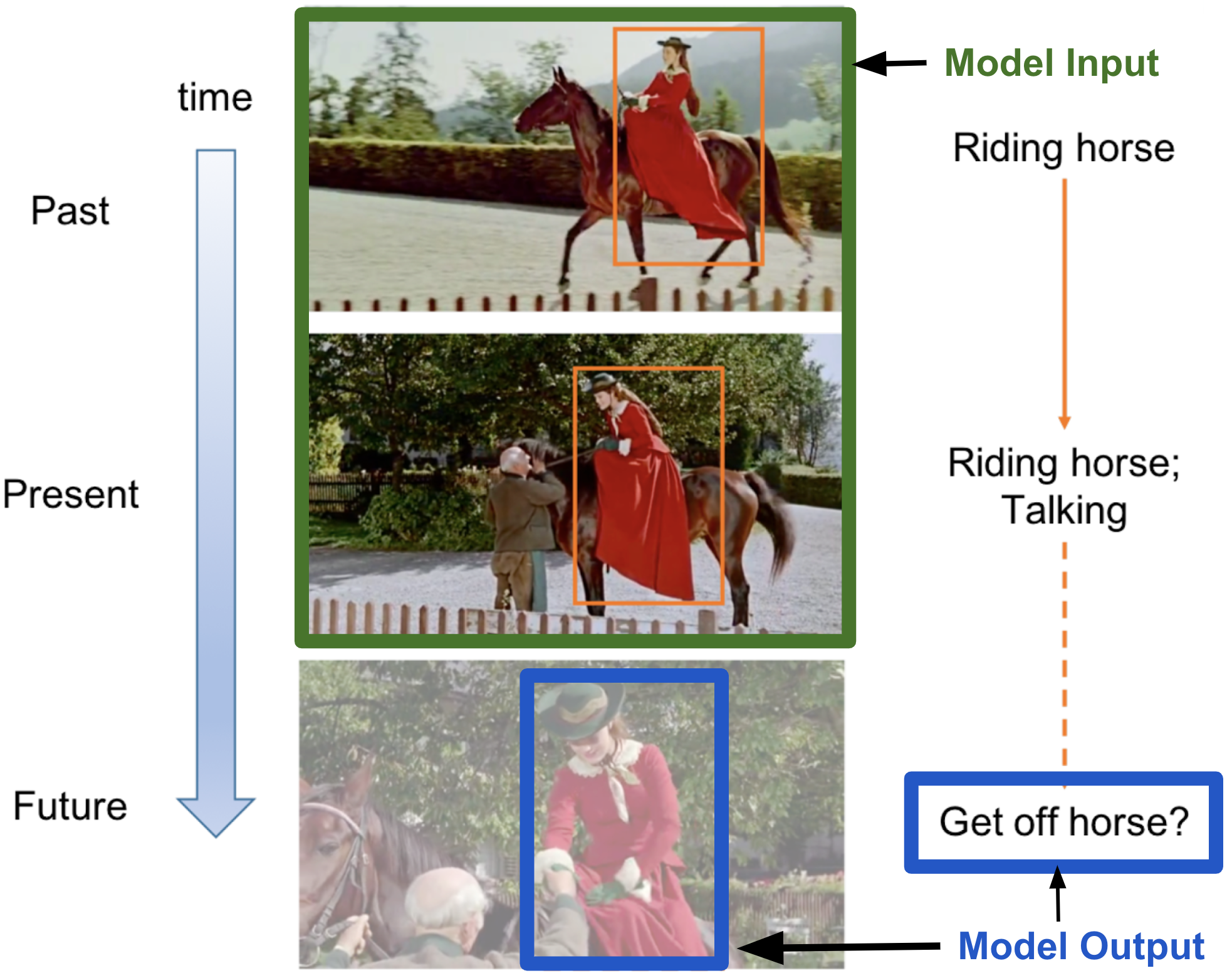

The following figure illustrates this second, more complex variant. The model takes as input the present and past frames (outlined in green), and outputs the location of the woman and probabilities of the action she might be performing next (outlined in blue). In this case, a possible future action by the woman is “get off horse,” and is shown for illustration purposes in the frame at the bottom of the figure (but that frame is not shown to the algorithm).

Figure 5. Illustration of action forecasting. Given past and present frames in a video, the task consists of predicting what action the agent will perform next, and its location. The image is adapted from [3].

Figure 5. Illustration of action forecasting. Given past and present frames in a video, the task consists of predicting what action the agent will perform next, and its location. The image is adapted from [3].

It is worth mentioning the importance of temporal dependencies for action forecasting. For example, it is more likely that the woman will dismount if she has just ridden towards the man than if she had just mounted. Only showing the frames where the woman is talking to the man does not provide all the relevant information about the past, and introduces a higher error rate in the prediction of the future.

Other Tasks

We have thus far presented five different tasks associated with video understanding. Here are some others:

- Story extraction: given a video, produce a complete description — or story — of a video, expressed in natural language.

- Object tracking: given a video and a set of object detections (locations of objects) in an initial frame and unique identifiers for each object, detect the location of each object in future frames.

- Text-video retrieval: given text that describes an action (e.g., “child playing football”), find all the videos in a video dataset where the action occurs. (YouTube’s search tool is an example of this task.)

The prestigious 2021 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition held two events on video understanding. The International Challenge on Activity Recognition included a competition in 16 video understanding tasks, including several of the tasks described above (and some variations of them). The Workshop on Large Scale Holistic Video Understanding focused on the recognition of scenes, objects, actions, and attributes of videos (including multi-label and multi-task recognition of different semantic concepts in real world videos). These events illustrate the intense level of activity in the field — activity that is likely to grow, as research continues to push the boundaries of video understanding capabilities.

Now that we have a better grasp on tasks associated with video understanding, let’s look more closely at some of their applications in the real world.

Video Understanding in the Real World

Video understanding has a wide range of applications. While in no way an exhaustive list, here we consider four domains of applications in particular: manufacturing, retail, smart cities, and elderly care.

Manufacturing

Video cameras are already used in many manufacturing settings, and provide a wealth of benefits. These include:

- Monitoring remote facilities

- Mitigating workplace hazards

- Improving security and detecting intrusion

- Auditing operations

- Monitoring and safeguarding inventory levels

- Ensuring safe delivery of materials

- Controlling and ensuring quality

Many of these benefits are gleaned simply by installing cameras and having humans review the footage. Often these cameras work in conjunction with additional sensors to augment and automate some of the processes mentioned above, but the utility of just about any of these tasks could be amplified with the addition of video understanding algorithms, in support of existing surveillance initiatives. For example, rather than manually reviewing footage to perform an operations audit, dense captioning could be employed to summarize operations automatically. Action forecasting could be used to better manage and predict inventory levels and potential shortfalls. Action recognition could help pinpoint workplace hazards and pitfalls, creating safer job sites.

Quality assurance in assembly lines is another area where video understanding could bring considerable utility by analyzing each step of activity on the manufacturing floor in real time, in order to reduce assembly errors. Specifically, video understanding technologies could create prescriptive analytic tools to accumulate statistics from assembly workstations, including life-cycle times, first-time yield, error rates, and step-level timings. Video understanding could also be used to trace back-errors after a defective product has been detected, or a product recall has been issued. This provides additional benefits, such as enabling industrial engineers to perform root cause analysis.

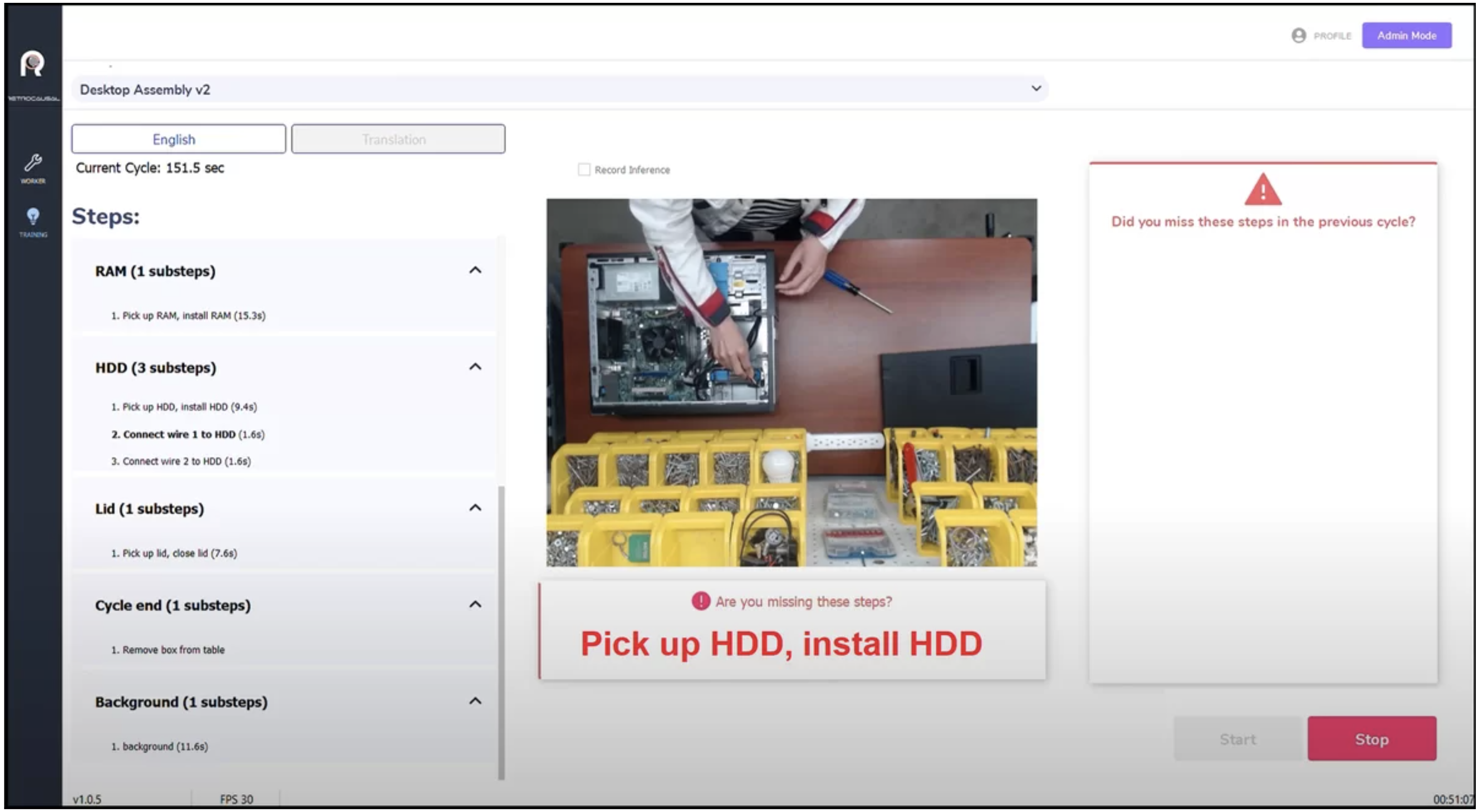

One example of how video understanding can contribute to increased product quality is an offering by Retrocausal.ai. The solution, called Pathfinder Apollo, can be used to detect when a worker makes a mistake in the assembly process. To illustrate how it works, on the left of Figure 6, below, is a list of the steps required to assemble a desktop computer, including the installation of different parts, like the RAM, the HDD, and the Lid. The list also includes steps required after the assembly, like removing the assembled piece from the table. Some of the steps have sub-steps.

Figure 6. Video understanding used in manufacturing. The system alerts a worker if an error may have been made in the assembly of a desktop computer. This image has been pulled from the Retrocausal site.

Figure 6. Video understanding used in manufacturing. The system alerts a worker if an error may have been made in the assembly of a desktop computer. This image has been pulled from the Retrocausal site.

The image at the centre of the figure is a frame taken from the video of the worker assembling the machine. It shows a workstation, the hands of the worker, parts of the desktop computer being assembled, tools, fasteners, and other pieces. The figure shows the moment at which the worker is being automatically alerted by the system that they might have missed one of the steps. The system detects this potential error in real time, and sends visual and sound alerts to the worker, asking them if they have missed a step, and indicating what that step might be — in this case, the installation of the HDD.

Retail

The retail sector has also long made use of video cameras in daily operations, and could benefit from video understanding in similar ways to many manufacturing scenarios — but unique to retail is the potential for video understanding to improve the customer experience, and to assess the efficacy of in-store advertisements.

To improve customer experience, for example, action forecasting combined with action detection could be used to better understand store layouts by considering the flow of customers throughout the store and their interactions with merchandise. This would then allow retail entities to better optimize their store layouts, including adjustments to aisle dimensions and product locations, to reduce bottlenecks and accommodate peak foot traffic hours.

Video understanding could also assess the effects of in-store advertisements. Analysis segmented by demographic data like age, gender, etc., can help correlate sales of specific products with advertisements, monitor “dwell time” (how long customers spend in each store area), and assess promotional campaign strategies.

One concrete example of how video understanding can contribute to the retail sector is the customizable dashboard offered by BriefCam as part of their video analytics solutions. The dashboard provides stores with information — like the number of visitors, the average duration of visits, and the maximum number of visitors per hour. In the example below, visitors are divided into three classes: women (who comprise 61.5% of the visitors), men (36.9%), and children ( 1.7%). Visitor counts are displayed per hour. Near the bottom right of the figure, trajectory maps and background changes are superposed on snapshots of the store, which help identify the areas most frequently visited, as well as customer flow.

Figure 7. Application of Video Understanding in retail. The

dashboard

image is taken from

BriefCam

provides information about a store’s number of visitors, average duration of a visit, typical customer trajectories within the store, and more.

Figure 7. Application of Video Understanding in retail. The

dashboard

image is taken from

BriefCam

provides information about a store’s number of visitors, average duration of a visit, typical customer trajectories within the store, and more.

Smart Cities

Smart cities aim to improve the quality of life in urban areas. To this end, they employ a wide range of electronic and digital technologies. The AI boom over the last ten years has accelerated the development of smart cities, and this is, in part, due to the capacity of AI to extract meaning from unstructured data like video footage. Video is particularly useful for the creation of smart cities, due to the relatively low cost of cameras, and the wealth of information that video footage can provide.

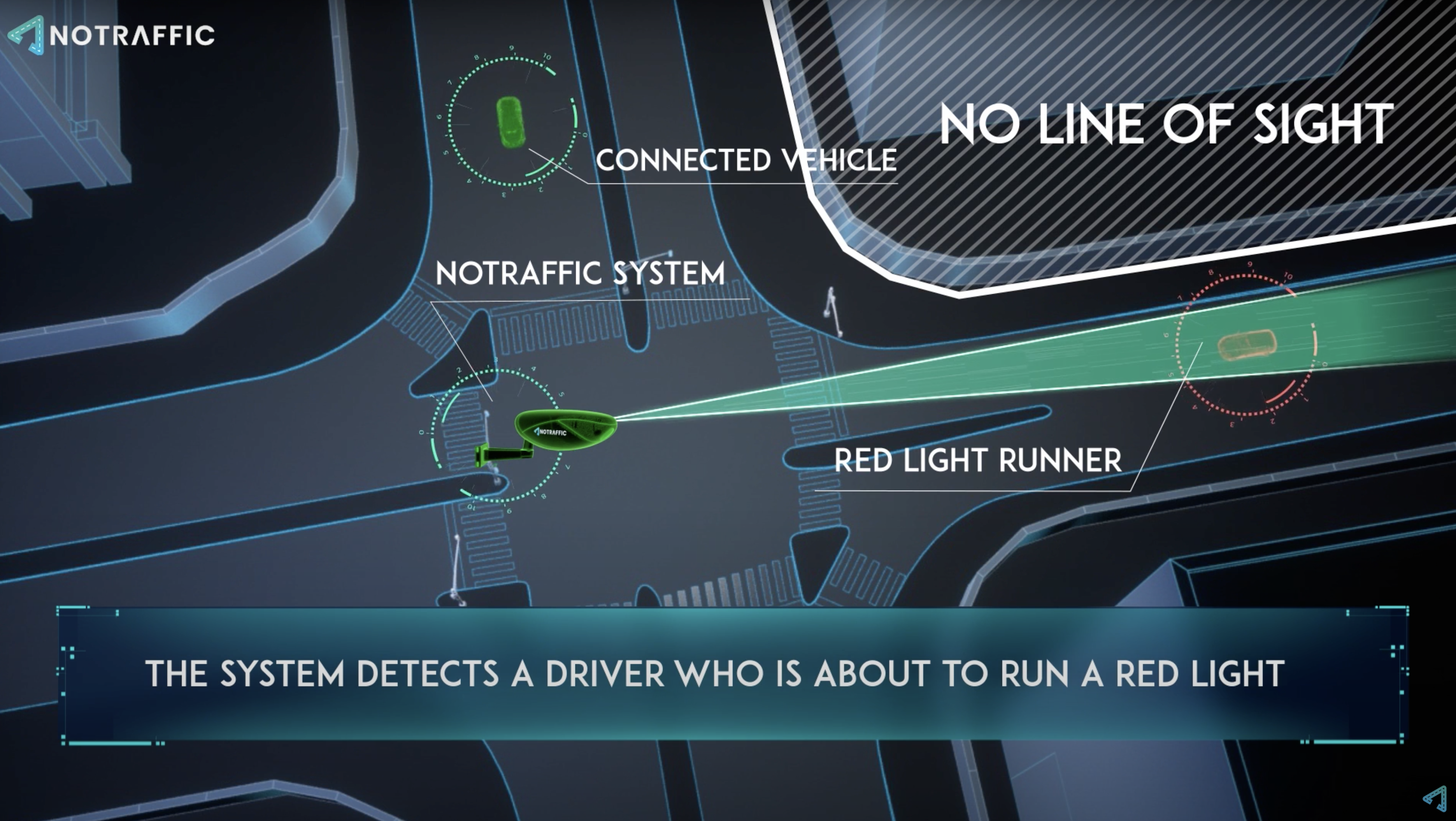

One of the many ways in which video understanding helps in the creation of smart cities is by making roads safer. For example, Figure 8 illustrates a platform built by a company called NoTraffic, which uses a camera to film vehicles and pedestrians near or at the intersection of two streets.

In this example, the platform detects a car (represented by a red icon at the right of the figure, labelled as “Red Light Runner”) that might run a red light. This detection could be done, for example, by the platform becoming aware that the light is red for that vehicle, and estimating that the vehicle’s speed might be too high for it to make a full stop on time.

The platform then sends an alert to another vehicle (green icon at the top of the figure, labelled “Connected Vehicle”) about the risk of a collision. This alert is particularly useful at a time when there is no line of sight between the vehicles.

Figure 8. Illustration of video understanding applied to the creation of smart cities. An alert is sent to a vehicle (represented by the green icon), for which the light is green, that there is another vehicle (represented by the red icon) who is likely to run a red light. This alert is particularly useful when there is no light of sight between the two involved vehicles, as in this case. Image taken from this video.

Figure 8. Illustration of video understanding applied to the creation of smart cities. An alert is sent to a vehicle (represented by the green icon), for which the light is green, that there is another vehicle (represented by the red icon) who is likely to run a red light. This alert is particularly useful when there is no light of sight between the two involved vehicles, as in this case. Image taken from this video.

The types of video understanding tasks that power applications like this include action forecasting. In this specific application, the agents are vehicles, rather than people. However, similar applications in smart cities may involve the interaction between human agents and vehicle agents, e.g., to warn a driver about a pedestrian or cyclist.

This kind of application might also benefit from multiview activity recognition, which consolidates information from multiple cameras. For instance, cameras fixed at the intersection would correspond to a third-party view, and cameras embedded in the vehicles themselves would correspond to ego-view. Together, multiple views would help in the creation of a more accurate predictive system than that of a single-view system.

Elderly Care

Another application of video understanding is facilitating aging-in-place. The Center for Disease Control in the United States defines aging-in-place as “the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level” —and, according to this article, nearly 90% of respondents to a survey of United Kingdom residents aged 55+ indicated a desire to “live independently as long as possible.” With an increase in an aging population that coincides with a shortage in staff to take care of the elderly, video understanding could be one of the technologies that facilitates aging-in-place. It can be used to detect accidents, health conditions, or events that place an elderly person at risk, such as forgetting to switch off the stove, or to take medicine.

This is another area in which the tasks of video classification and action recognition could form part of the technologies powering the system for elderly care. Additionally, multimodal action recognition could be used: the signals from acceleration sensors worn by an elderly person could be used in conjunction with video information from cameras to detect accidents, like falls.

Ethical Considerations

With great capabilities come great responsibilities. The ubiquitousness of cameras, together with the ability to extract information from video, makes video understanding a prime subject for ethical inquiry. Just some of the many ethical considerations are:

- Which entities (individuals, organizations, governments, etc.) should have the right to capture and analyse video belonging to other entities?

- When, where, how, and under what circumstances should those entities be allowed to carry out that capture and analysis?

- To what extent can video understanding capabilities be said to be ethically neutral?

- To what extent can it be said that ethical considerations are relevant only when those capabilities are applied?

For instance, monitoring of the elderly may infringe on the right to privacy beyond their expectations, and therefore diminish their dignity. Surveillance and smart cities may increase safety, but that may come at the expense of privacy. Video understanding may improve customer experience, but may involve psychological manipulation.

The answers to these questions will vary with time, depending on a wide range of political, social, economic, cultural and technological factors. The processes through which those questions need to be addressed are political in nature — “politics” here understood as “the art of making collective decisions.” At an enterprise level, one of the responsibilities of organizations is to provide relevant and accurate information that informs the ethical discussion of society at large.

This section has only touched the surface of a wide and complex subject. In addition to the themes above, and as AI increasingly underlies video understanding, ethical concerns about AI (such as bias in training data sets, among many others), are inherited by video understanding. Here are some additional resources for the interested reader: Surveillance Ethics, The Ethics of Video Analytics, and The Ethics of AI for Video Surveillance.

Summary

Video understanding is a fascinating field that aims to extract rich and useful information from video. In this blog post, we have presented several capabilities (i.e., tasks) and applications of video understanding.

Tasks are the ways in which machine learning practitioners formulate and make concrete the problem of video understanding. We have described five: video classification, action detection, dense video captioning, multimodal and multiview activity recognition, and action forecasting. Tasks are often used as building blocks of video understanding systems deployed in real world applications.

We have also presented four areas of application of video understanding — manufacturing, retail, smart cities, and elderly care — and have shown how those applications might use some of these video understanding tasks.

Last, we mentioned some of the ethical questions that become increasingly urgent to address video understanding technolgoies become more powerful.

Next Steps

To start experimenting with video understanding, check out the applied prototype (also mentioned at the beginning of this post). The repository focuses on Video Classification and demonstrates:

-

How to download, unpack, and explore Kinetics, a popular dataset used for AI-based video classification. Getting familiear with a dataset is an excellent way to get a deep sense of capabilities.

-

How to download and experiment with a pre-trained AI model for video classification, namely Two-Stream Inflated 3D ConvNet, or I3D. This is a relatively simple model that is useful for understanding the capabilities.

References

[1] Dense-Captioning Events in Videos, Krishna et al. 2007.

[2] Home Action Genome: Cooperative Compositional Action Understanding, Rai et al. 2021.

[3] Relational Action Forecasting, Sun et al. 2019.