May 5, 2022 · post

Neutralizing Subjectivity Bias with HuggingFace Transformers

Subjective language is all around us – product advertisements, social marketing campaigns, personal opinion blogs, political propaganda, and news media, just to name a few examples. From a young age, we are taught the power of rhetoric as a means to influence others with our ideas and enact change in the world. As a result, this has become society’s default tone for broadcasting ideas. And while the ultimate morality of our rhetoric depends on the underlying intent (benevolent vs. malevolent), it is all inherently subjective.

However, there are certain modes of communication today like textbooks, encyclopedias, and [some] news outlets that do strive for objectivity. In these contexts, bias in the form of subjectivity is considered inappropriate, yet it remains prevalent because it is our rooted, societal tone. Subjectivity bias occurs when language that should be neutral and fair is skewed by feeling, opinion, or taste (whether consciously or unconsciously)1. The presence of this type of bias concealed within a supposedly objective mode of communication has the potential to wear down our collective trust and incite social animosity as opinions are incorrectly perceived as fact.

Since maintaining a neutral tone of voice is challenging and unnatural for humans, successful automation of this task has the potential to be useful for neutrality-striving authors and editors. Of course, this is no easy feat. In this blog post, we introduce our approach to automatically neutralizing subjectivity bias in text using HuggingFace transformers. Let’s dive in!

Neutralizing Subjectivity Bias

As discussed in our previous blog post, Text Style Transfer (TST) is a natural language generation task which aims to automatically control the style attributes of text while preserving the content.

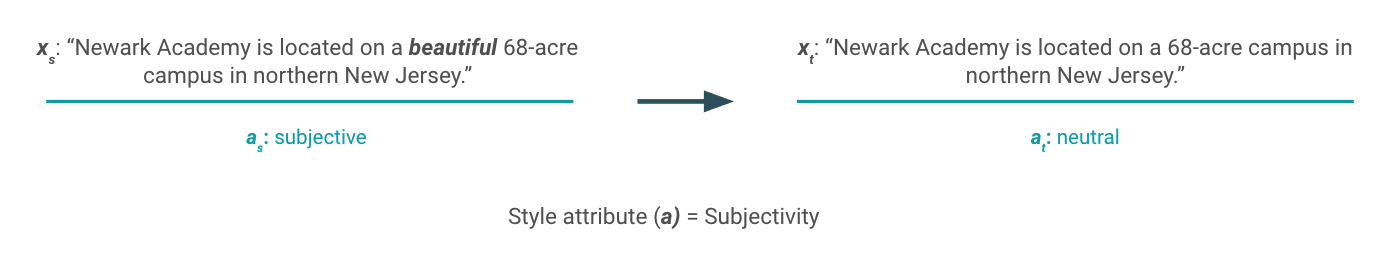

In this sense, the task of “neutralizing subjectivity bias” casts subjectivity as the style attribute. Given a subjective sentence, the goal is to generate a modified version of the sentence with the same semantic meaning, but in a neutral tone of voice. In the example below, we see that the source sentence uses the adjective “beautiful” when describing “Newark Academy’s campus”, which is a subjective intensifier that implies the author’s feelings about the topic at hand. This sentence can be “neutralized” simply by removing the subjective term as seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Example of text style transfer that brings inappropriately subjective text into a neutral point of view.

A successful endeavor in this task is predicated on the ability to accurately define and model subjectivity, which is a challenge even for humans because the notion of subjectivity can be… well, subjective. Not all written manifestations of subjectivity bias are this obvious, and consequently, they often cannot be alleviated by a simple rule to remove a modifier word as we’ll see in later examples.

Luckily, there exist open bodies of knowledge like encyclopedias that do adhere to standards of neutral-toned language. For example, Wikipedia strictly enforces a Neutral Point of View (NPOV) policy which means representing content fairly, proportionately, and, as far as possible, without editorial bias2. To uphold the policy, an active community of editors are incentivized to identify and revise passages that are in violation of NPOV to attain encyclopedic content with a standard tone of neutrality.

Dataset: The Wiki Neutrality Corpus (WNC)

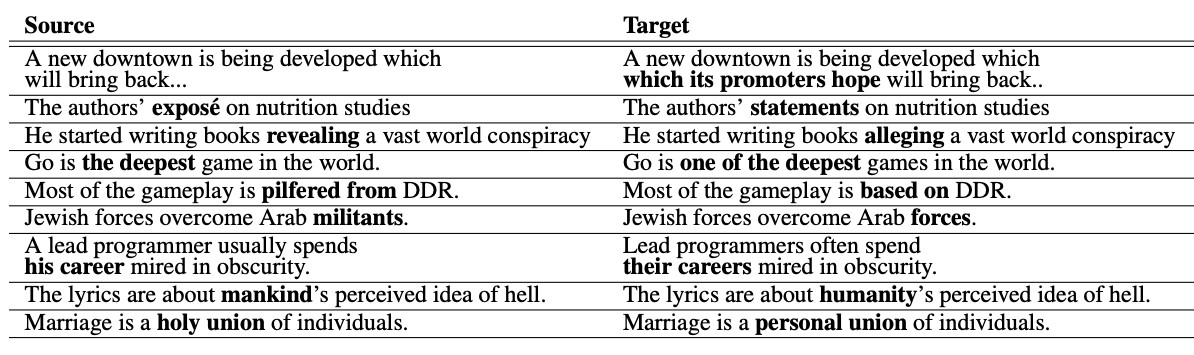

Because Wikipedia enforces this neutrality policy and maintains a complete revision history, the encyclopedia edits associated with an NPOV justification can be parsed out to form a dataset of aligned (subjective vs. neutral) sentence pairs. This realization led to the creation of the Wiki Neutrality Corpus (WNC) – a parallel corpus of 180,000 biased and neutralized sentence pairs along with contextual sentences and metadata – which we will use as the body of knowledge for our TST modeling endeavor. A few examples from WNC are displayed in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Samples from the Wiki Neutrality Corpus that demonstrate sentences before and after neutralization edits are made.

Since the WNC is a parallel dataset (see our previous post for discussion of parallel vs. non-parallel datasets), we can formulate our task of “neutralizing subjectivity bias” as a supervised learning problem. In this regard, we indirectly adopt Wikipedia’s NPOV policy as our definition of “neutrality” and aim to learn a model representation of these policy guidelines directly from the paired examples. But what exactly constitutes Wikipedia’s NPOV policy and how are these guidelines realized in practice?

The NPOV policy does not claim to allow only neutral facts or opinions. Rather, the goal is to present all facts and opinions neutrally (without editorial bias), even when those ideas themselves are biased3. NPOV advocates the following guidelines to achieve a level of neutrality that is appropriate for an encyclopedia2:

- Avoid stating opinions as facts

- Avoid stating facts as opinions

- Avoid stating seriously contested assertions as facts

- Prefer non-judgemental language

- Indicate the relative prominence of opposing views

Upon analyzing actual examples of bias-driven NPOV edits in Wikipedia that result from this policy, the authors of Linguistic Models for Analyzing and Detecting Biased Language and Automatically Neutralizing Subjective Bias in Text observed and categorized several underlying types of bias that appear throughout the WNC: framing bias, epistemological bias, and demographic bias.

Framing Bias

Framing bias is the most explicit form of subjectivity bias and is realized when subjective words or phrases are linked to a particular point of view. As we saw in the example above, the adjective “beautiful” was used to describe the “68-acre campus”. These types of subjective intensifiers add directional force to a proposition’s meaning, and therefore reveal the author’s stance on a particular subject4.

Epistemological Bias

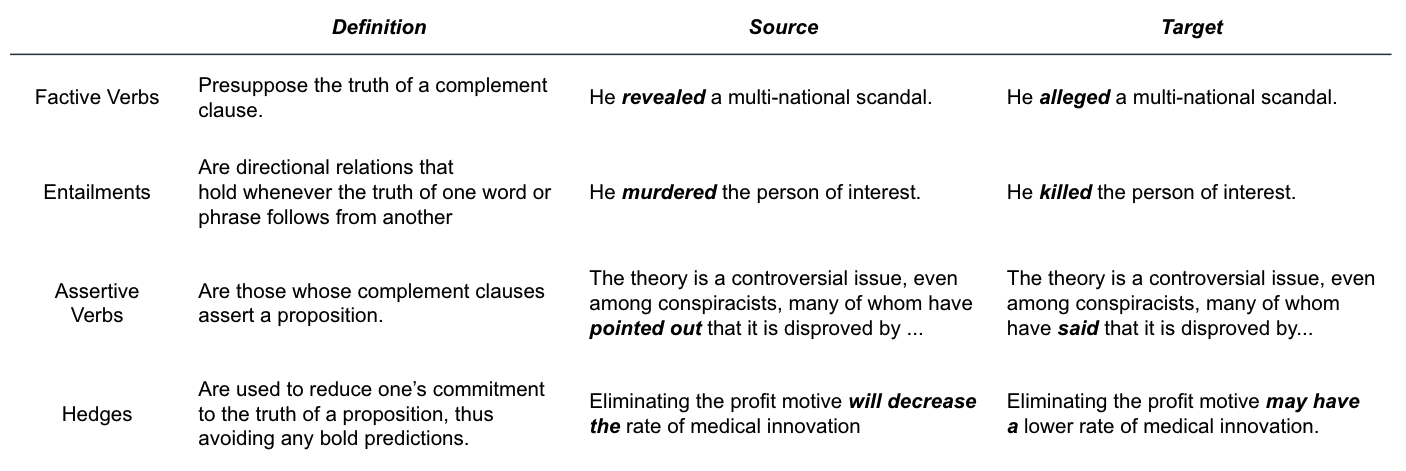

Epistemological bias results when using linguistic features that subtly presuppose the truth (or falsity) of a proposition and in doing so, modifies its believability. In this way, the author surreptitiously conveys a particular attitude or viewpoint onto the reader in an implicit manner. This type of subjectivity bias is much harder to discern and is often delivered via factive verbs, entailments, assertive verbs, and hedges.

Figure 3: Common ways in which epistemological bias is surfaced with corresponding examples.

In the first line of Figure 3 above, we see that the term “revealed” is neutralized to “alleged”. This is a clear example of epistemological bias where a factive verb (“revealed”) is used to imply some truth about the subject (“a multinational scandal”), which ultimately may or may not be rooted in fact.

Demographic Bias

Similar to epistemological bias, demographic bias occurs when an author utilizes language that implicitly presupposes truth about people of particular gender, race, religion, or other demographic group. For example, presupposing that all programmers are male through the choice of assigned pronouns1.

For more detailed discussion on these classes of subjectivity bias, please see this excellent source paper where these definitions and examples are adapted from.

Modeling Approach

Now that we have an understanding of the TST task at hand and are familiar with the dataset we’ll be using, let’s discuss our approach to solving the problem. We will formulate Text Style Transfer as a conditional generation task and fine-tune a pre-trained BART model on the parallel Wiki Neutrality Corpus in similar fashion to a text summarization use case.

Let’s dig into what this means.

Conditional Generation

Recall our goal from earlier: Given a subjective sentence, the goal is to generate a modified version of that sentence with the same semantic meaning, but in a neutral tone of voice.

Figure 4: High level TST objective where the goal is to generate output text provided some input text.

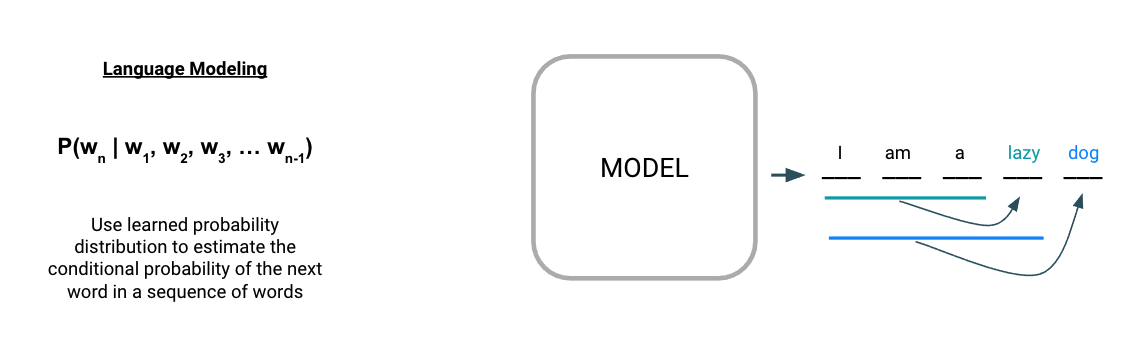

By default, we have a generative modeling problem. But how do we go about generating text? It all starts with a language model, which is fundamental to most modern NLP tasks. At its core, a language model is a learned probability distribution over a sequence of words. We can use this probability distribution to estimate the conditional probability of the next word in a sequence, given the prior words as context.

Figure 5: Autoregressive language modeling uses a learned probability distribution to estimate subsequent tokens provided an initial sequence of tokens.

In Figure 5 above, we see that starting with the input sequence “I am a”, the language model is able to iteratively generate subsequent words, one at a time. This describes the fundamental workings of a common NLP method called autoregressive language modeling where the goal is to predict future values from past values (i.e. guess the next token having seen all the previous ones). The notable GPT (and all its descendants) is a popular example of this type of model.

While this is an effective strategy for generating text broadly, it is insufficient for our TST task because for TST we need to generate text that is conditioned on our input sentence. Notice that autoregressive models can only generate text a.) based on the statically learned language model and b.) provided an initial sequence of words as a prompt for it to auto-regressively continue on with. In the case of TST, we do not have an initial sequence of a few words as the prompt, rather we have a complete sentence as the prompt that needs to be rewritten from scratch.

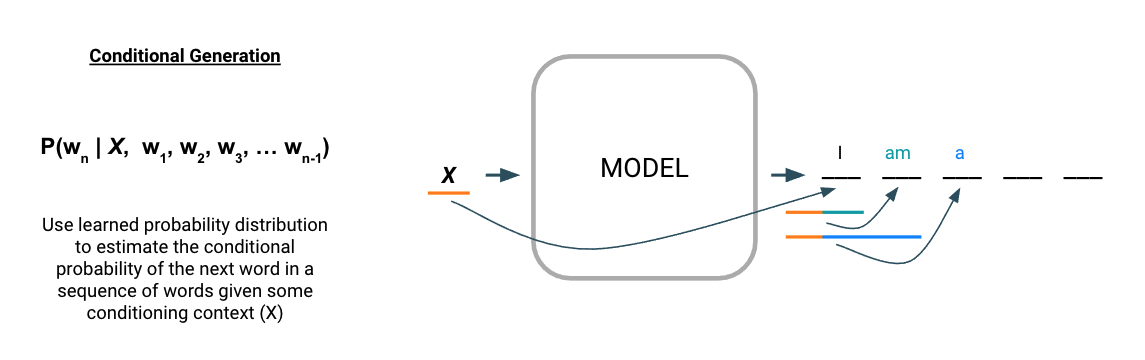

What we actually need is a sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) model to allow for conditional text generation.

Figure 6: Conditional language modeling uses a learned probability distribution to estimate subsequent tokens conditioned on some input context.

As the name suggests, seq2seq models generate an output sequence conditioned on an input sequence and are the standard class of models for tasks like machine translation, summarization, and abstractive questions answering. In Figure 6 above, we see that the input context X is used by the model to generate the first output word (“I”). The generation process then continues in an autoregressive fashion similar to the standard language model, except that for each new term generated, the output is based on the sequence generated thus far as well as the input context (X).

This high level discussion helps develop intuition for the general modeling approach (inputs/outputs), but omits many fine details. What is this blackbox language model and how does it “learn” probability distributions over sequences of words? How can it understand the intricate factors that determine subjective vs. neutral language? And how does this model actually condition its outputs based on some input?

We’ll answer these questions by taking an indepth look at one particular seq2seq model used in our experimentation called BART and see how it operates as a pre-trained language model.

BART as a Conditional Language Model

Self supervision is a strategy by which models can learn directly from unlabeled data (text in this case), which is crucial for our TST application because we only have a limited number of labeled examples in our parallel WNC corpus. Therefore, self supervised learning (SSL) allows us to first pretrain a model on enormous bodies of unlabeled text to develop a basic understanding of the English language (i.e. develop a language model). We can then fine-tune this robust representation with the smaller set of parallel training examples from WNC to hone in on the specific patterns attributed to subjective vs. neutral language – a standard process known as transfer learning. For a more detailed review on this topic, see our report FF11: Transfer Learning for Natural Language Processing.

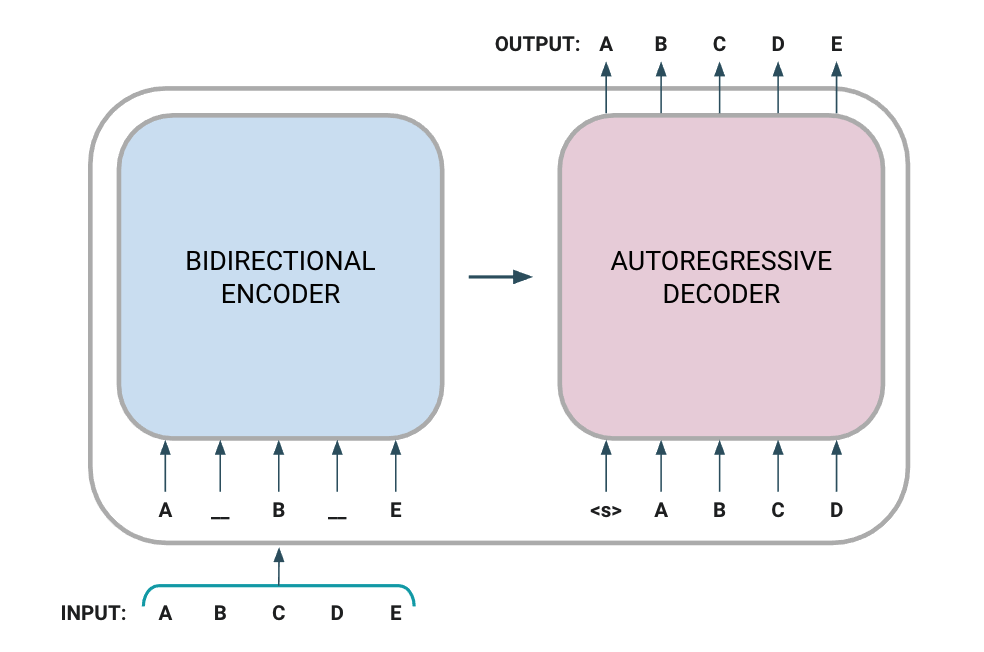

BART is one instance of a model that can be used for self-supervised learning on text data. In particular, BART is a denoising autoencoder that uses a standard Transformer-based architecture for pretraining sequence-to-sequence models, but with a few tricks.

Figure 7: BART is implemented with a bidirectional encoder over corrupted text and a left-to-right autoregressive decoder that attends to the encoded latent representation to generate an output that minimizes the negative log likelihood of the original input document. Image is adapted from the source paper.

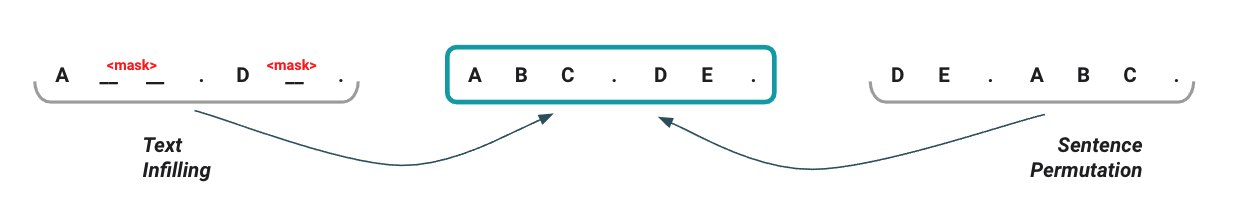

BART is pre-trained in a self-supervised fashion on 160GB of news, books, stories, and web text by corrupting input sentences with a noising function and then learning a model to reconstruct the original text (i.e. denoising the corrupted signal)5. The corrupting function works by randomly applying the following transformations (as depicted in Figure 8 below):

- Text Infilling: A number of text spans (zero-length, single, or multiple words) are sampled and hidden with a mask token. This teaches the model to predict if, how many, and which tokens are missing from a segment of the sentence.

- Sentence Permutation: Input sentences are shuffled in random order in order to teach the model to structure logical statements sequentially.

Figure 8: The two noising transformations that were empirically selected by BART’s authors. Image is adapted from the source paper.

In Figure 7 above, we see how noise is first introduced to the input text sequence as tokens are randomly masked. The corrupted document is then processed by a bidirectional encoder (which attends to the full input sequence, forward and backward) to extract out a latent representation of the input. This latent representation gets passed on to the decoder which auto-regressively generates an output sequence conditioned on the latent representation. Reconstruction error is calculated with cross-entropy loss by comparing the original input sequence with the decoder’s output (i.e. did the model reconstruct the corrupted input correctly?).

Rather than introducing novel techniques, BART’s effectiveness comes from combining the strengths of many advances before it into one empirically driven, cohesive strategy – the architecture of original Transformer, bidirectional encodings from BERT, autoregressive generation from GPT, longer training + larger batch sizes + longer sequences + dynamic masking from RoBERTa, and span masking from SpanBERT.

Establishing a Baseline

As with any machine learning problem, it’s important to establish a baseline model to serve as a performance benchmark to measure progress against. Upon releasing the WNC dataset, the authors simultaneously released their modeling approach, dataset splits, and results for this TST task, which serve as an excellent benchmark for us to levelset our modeling approach against.

Competitive Benchmark

The paper authors limited their experimentation to a subset of the dataset that only includes NPOV-edits where the Wikipedia editor changed or deleted just a single word in the source text. From our study on the types of bias present in WNC above, we infer that a larger portion of the revisions in this sample consist of framing bias (the most explicit, and therefore easiest type of subjectivity to identify and correct) in comparison to the full WNC corpus. This choice resulted in using just a quarter of the full dataset (~54,000 training pairs) and from that, the authors separated out a random sample of 700 pairs for a development set and 1000 pairs for a test set.

The authors employ two modeling approaches that are both based on an encoder-decoder architecture similar to BART, but with several key differences including the noising function, decoder model type (LSTM RNN vs. attention-based Transformer), and training configuration. For a full description of their modeling setup, see Section 3 of the paper.

The authors quantitatively assess their model performance with two metrics – BLEU score and accuracy.

- BLEU score (bilingual evaluation understudy) is a common metric used to evaluate the quality of machine translation outputs by looking at the overlap of words and n-grams between a model generated output and a human-generated reference example. BLEU scores range from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 represent higher degree of similarity.

- Accuracy here is defined as the proportion of all decodings that exactly matched the ground truth references.

Across the two modeling approaches, the author’s achieve maximum scores of 93.94 BLEU and 45.80 accuracy on the one-word subset of WNC.

Implementing BART on WNC

The WNC corpus comes cleanly packaged with sentence pairs “pre” and “post” edit for each revision. Prior to modeling the one-word subset with BART, some light exploratory analysis was performed to inform preprocessing decisions.

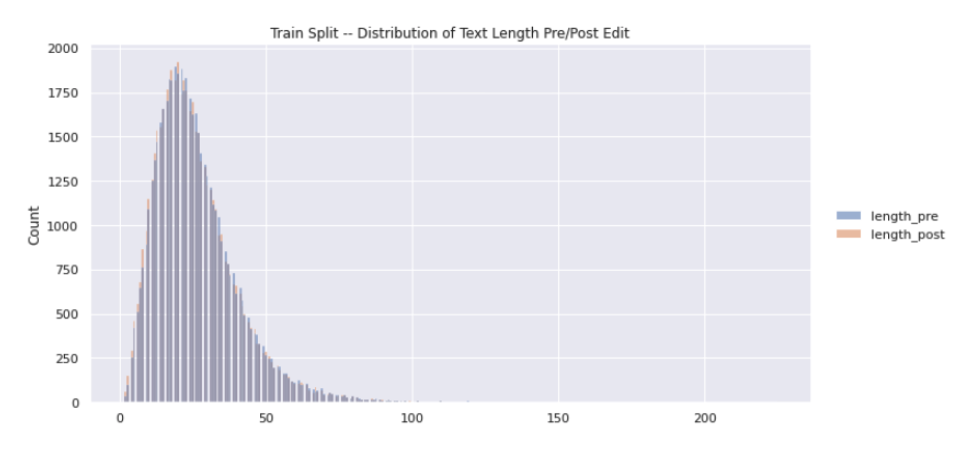

Figure 9: Histogram plot depicting the distribution of text length (both pre and post edit) for all revisions in the training set. Since this plot visualizes both pre and post edit lengths, there are actually ~108k data points represented here (54k each).

The distribution of text length (when naively tokenized by whitespace) is consistent across the provided train/dev/test splits with a median sentence length of 23 tokens. From Figure 9 above, we see that there is a long right tail of sentence pairs by length indicating some potential outliers or data quality issues.

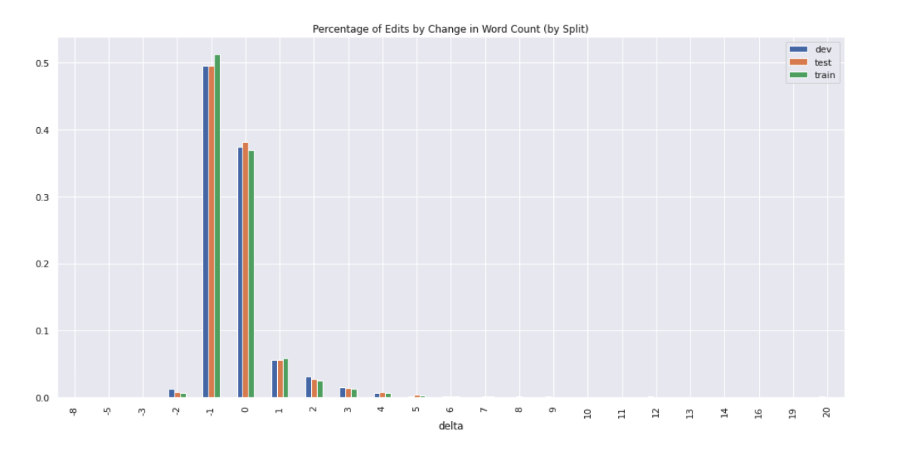

Figure 10: The distribution of revisions by the net change in word count (pre and post edit) expressed as a percentage of total revisions.

When looking at the percentage of sentence pairs grouped by the change in word count before and after the editing (Figure 10), we see that ~50% of revisions are subtractive in nature (i.e. delete one word) and ~38% are net-even in sentence length (i.e. replacing one word). Oddly, we observe some examples where two or more words are removed, which is unexpected given the definition of this subset from WNC.

To account for all of these concerns, the following preprocessing steps are taken:

- Remove records with a pre-edit sentence length above the 99th percentile

- Remove records with a pre-edit sentence length below the 1st percentile

- Remove records with a net subtraction of more than one word

- Remove records with a net addition of more than 4 words (manual inspection shows these are caused by data quality issues like improper punctuation)

For modeling, we make extensive use of the mighty Huggingface transformers library by saving WNC as a HuggingFace dataset, initializing the BartForConditionalGeneration model with facebook/bart-base pretrained weights, and adapting the summarization fine-tuning script for our TST-specific needs. We fine-tune the model for 10 epochs on an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU with a batch size of 8, evaluating BLEU and accuracy (with beam search + beam width of 4) every 1000 steps. (Note that when fine-tuning the model with the parallel examples, the noising function is turned off so an uncorrupted document is passed to both the encoder and decoder.)

The best model from training achieves 93.36 BLEU and 47.39 accuracy. While our results are competitive, they cannot be directly compared with the WNC authors’ because of differences in preprocessing. Despite this, they do provide sufficient validation of our approach as a means to automatically neutralize subjectivity bias in text.

Next Steps

Our efforts thus far in developing a baseline model have affirmed our modeling approach and laid a foundation to improve upon. With that, there are several areas of this problem space that warrant further experimentation.

- Expand the problem scope. The scope of this initial modeling exercise was limited to just single-word edits which are largely attributed to the simplest instances of subjectivity bias. By working with the full WNC corpus that includes multi-word edits, we can understand the challenges of modeling more nuanced instances of subjectivity bias.

- Explore alternate evaluation metrics. Evaluating TST with BLEU score and accuracy allowed us to benchmark performance in a consistent manner. However, these metrics aren’t without limitation and may not be the best or most comprehensive way to characterize the meaning of a “good” style transfer.

- Improve modeling approach. Our baseline model was the result of simple fine-tuning. There is opportunity to explore different model hyperparameters, loss functions with targeted rewards, and pre-training strategies to make use of the “neutral” text that accompanies the sentence pairs.

We look forward to exploring these ideas, documenting our progress, and releasing our experimental code & models in the next post. Stay tuned!